The piece of the month of October 2019

TWO SILVER PIECES FROM THE BROTHERHOOD OF SAINT ELOY OF THE SILVERSMITHS IN THE CHURCH OF SAN SATURNINO IN PAMPLONA

Eduardo Morales Solchaga

Chair of Navarrese Heritage and Art

It was not until the disappearance of the House of Evreux in Navarre that attend witnessed an unprecedented corporate boom in the capital. In the second half of the 15th century, the collapse of royal power encouraged the emergence of guilds, with strong municipal participation. The guilds of official document underwent an expansion B , becoming authentic professional groups, with certain advances in the form of organisation of work. The 16th century was more favourable for the consolidation and foundation of new guilds of official document, once the incorporation into the Crown of Castile had been executed de facto, after the failed attempts at reconquest by the House of Foix. Apart from new foundations, some old ordinances concerning other brotherhoods were also reformed.

In this context, there is evidence of the existence of a confraternity of Pamplona silversmiths under the patronage of Saint Eloy from the late Middle Ages leave average , although its canonical organisation was established in 1554. Most of the silversmiths were located in the old neighbourhood of San Cernin, which is why they established their religious headquarters in the parish church of San Saturnino de Pamplona, located in the heart of the aforementioned borough. There they had their own altar, which was attached to the pillar on the epistle side of the main chapel, baroque in style by the altarpiece maker Juan Barón de Guerendiáin, where they celebrated both the funerals of the deceased brothers and the ordinary religious functions under the direction of the chaplain of the brotherhood: the birth and death of patron saint (25th June and 1st December), Corpus Christi and Our Lady of the Way.

During the 19th century, the relationship between the parish church and the brotherhood of San Eloy languished, in a process parallel to the dissolution of the guild in 1838. refund So much so that in 1886, on the initiative of the vicar general Don Felipe Tarancón, who wanted to return the church to its original lines, the altarpiece described above was dismantled. Since then, only a few vestiges recall a relationship of more than three centuries between the parish and the confraternity: the Romanesque image of the saint that presided over the altarpiece, today located in the sacristy, and two pieces of gold and silver work produced by the brotherhood, which are studied below and which since the 1990s have been exhibited in the museum of the San Saturnino workhouse.

The first of these is the reliquary of Saint Eloy, of which only the virile (12.5 cm) is preserved. Thanks to the documentation preserved in the brotherhood's file , the circumstances of its creation are known. It is the piece made at the time of his master's examination by Luis de Haudris (Odri), a French craftsman living in the city, who married Francisca de Ciga, widow of the master silversmith José Montalvo. On 11 June 1722 he presented the piece to the brotherhood, in accordance with the design he had previously made (he had decided not to make a jug or a chalice), which is preserved today in the book of examinees kept at the file Municipal de Pamplona. With this he obtained the degree scroll of master and the School to exercise the official document throughout the kingdom, becoming a member of the brotherhood after paying 24 reales for the entrance fee, 176 as alms, and a further 256 in substitution of the collation that was customarily given to the members of the brotherhood.

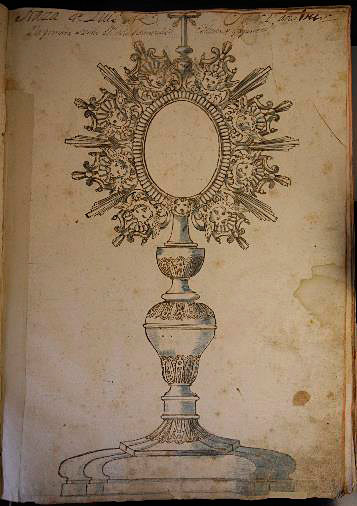

Drawing of a reliquary. Louis of Odri (1722). AMP.

The design, the first certified by Esteban de Gayarre as secretary of the brotherhood, sample a reliquary that follows the widespread morphology of the oval sun. It has a lobed base, a shaft with a cylindrical neck, a pear-shaped knot divided in two, a concave moulding, a average sphere, and a truncated cone body that joins it to the virile. The shaft alternates plain stripes with decorated spaces, the ornamentation of which consists of lance-shaped leaves and striations on lustre-painted scrolls. The sun has an oval virile, surrounded by a glory composed of straight bursts alternating with pairs of venerated 'C's', including angels' heads, and topped with a cross.

If we observe both the design and the preserved piece, we can see notable differences in its execution, which is somewhat simpler. Only the virile is preserved, although its foot may have been used in the reliquary of Saint Barbara in the same collection. However, when reducing the piece, Odri removed the angel heads mentioned above reference letter. On the obverse, protected by a bevelled glass, the effigy of Saint Eloy is painted on a sheet of tin, without any attribute identifying his work as a goldsmith, wearing a pontifical vestment; on the reverse, under a similar protection, is the bony remains of the saint, accompanied by the following registration: S[ancti] Eligii Epi[scopi] C[onfessoris]. As for the marking, the sun has no stylus, so it is more than likely that it was found on the foot. If we take as reference letter that of the reliquary of Santa Barbara, it only has a locality mark, which is clearly consistent with the hypothesis that it was the original of the reliquary discussed here, since as it is an examination piece it is unlikely that the author's mark was stamped, as this was acquired once it had passed the test.

Reliquary of Saint Eloy. Obverse. Parish Church of San Saturnino (1722).

The fact that an examination piece, which was later sold by weight or reduced, has been preserved is exceptional and is determined by an event parallel to its execution: the arrival in Pamplona of a relic of Saint Eloy from the hands of the secretary of the Ecclesiastical Tribunal of the Bishopric of Pamplona, Juan Fermín de Villanueva, after his stay in Rome in 1721. That same year he was paid 82 reales for this task, and 24 reales and 24 maravedíes were sent to the commissioner Francisco de Párraga, for certify the indulgences granted by Clement XI on 30 July, three plenary and many partial indulgences, at the Tribunal of the Holy Crusade.

The brotherhood decided to celebrate such an important event on Saint Eloy's Day in 1722, two weeks after presentation , taking advantage of Luis de Odri's work and paying him 396 reales for the 44 ounces of silver that he had employee in the reliquary, which was slightly modified, investing 2 reales in re-sheathing the glass of the virile. Also 44 reales and a half reales were spent on a small box with its "ferro y clavazón", to contain the relic of the saint patron saint.

Expenditure on wax tripled, exceeding 265 reales, as the high altar was illuminated throughout the day, decorated by the parish carpenter. The celebration, accompanied at all times by the chapter of San Saturnino, consisted of high mass, tedeum and enclosure (of the Blessed Sacrament). The aforementioned Juan Fermín de Villanueva paid part of the 9 ducats given to the collector Simón de Eugui for the music of the celebrations with his pecuniary. For his part, the sermon was paid to position by Father lector Yoldi, who received 64 reales in two instalments.

From then on, the relic, guarded by the guild authorities, presided over the annual celebrations of the saint, and was offered for adoration to the brothers by the brotherhood's chaplain. On special occasions, it was carried to the home of a sick brother, who, through the saint's intercession, hoped to be cured, as in the case of the Pamplona silversmith Antonio de Navaz in 1779. Even in 1815, after the War of Independence, it remained in the hands of the brotherhood, together with the trousseau destined to adorn the saint patron saint, consisting of mitre, crozier and pectoral. With the dissolution of the guild, it became part of the treasury of San Saturnino.

Reliquary of Saint Eloy. Reverse. Parish Church of San Saturnino (1722).

As for the examiner's career, Luis de Odri died five years after being examined, in 1727. Apart from the reliquary of Saint Eloy, only one ciborium by him has been preserved in Gipuzkoa, in the church of Arama.

The other piece preserved in this collection which is worth mentioning is a gilded silver chalice with a registration which runs along its base and accredits its provenance: DADIVA DE LA HERMANDAD DE PLATEROS DE PAMPNA A N.RA S.A DEL CAMINO. AUGUST 24, 1776. It has a circular base of profile truncated cone, a shaft with a periform knot and a bell-shaped cup that differentiates it from the sub-cup. The decoration, based on rockery and foliage, surrounds the piece, while the base is decorated with Christological figural themes (Lamb, pelican and sepulchre), alternating with pairs of angel heads.

Chalice of Saint Saturnin (1776).

Unfortunately, with the exception of registration, nothing is known about it, as there is a documentary gap in the last account book of the brotherhood of San Eloy, which affects the 100 pages containing the balances from 1771 to 1788. Nor does it bear any mark, either of authorship or locality, perhaps because it is an exceptional donation, in the body of the community.

In any case, observing what happened to other brotherhoods in the capital, it is known that the workers of the parish of San Saturnino called them together for the inauguration of the chapel of the Virgen del Camino on 25 August 1776. According to the chronicle, when the image was placed in the new chapel, the brotherhood of San Eloy attended behind the standard-bearer, together with the other guilds of the city. The following day they also took part in the procession, with the order "not to stop anywhere but only to enter the church of San Cernin through the main door, to pay homage to Our Lady, and to leave through the small door under the choir".

Chalice of Saint Saturninus (1776). Decoration of the base.

The fact that the confraternity of San Eloy contributed to the chapel's trousseau with the chalice is not unusual, as other similar associations also made interesting donations: the Santa Bárbara merchants' guild donated a set of sacras and silver cruets, the guild of pelaires did the same with a white chasuble, and the brotherhood of tailors gave a pallium to the workmen's guild.

SOURCES AND BIBLIOGRAPHY

file of the Brotherhood of San Eloy of Pamplona. Books of accounts and examinations.

file Municipal of Pamplona. Guilds and brotherhoods. Brotherhood of Silversmiths of Pamplona. Drawings of examinees.

ALBIZU Y SÁINZ DE MURIETA, J., La Virgen del Camino. Historia breve de la aparición y culto en Pamplona, Pamplona, Viuda de Aramburu, 1924.

GARCÍA GAÍNZA, M.ª C., Ancient drawings by the silversmiths of Pamplona, Pamplona, University of Navarra, 1991.

GARCÍA GAÍNZA, M.ª C., "San Eloy" in Pamplona and San Cernin 1611-2011. [Catalog de la exhibition], Pamplona, Pamplona City Council, 2011.

IRURITA LUSARRETA, M. A., El municipio de Pamplona en la Edad average, Pamplona, Pamplona City Council, 1959.

MIGUÉLIZ VALCARLOS, I., El Arte de la Platería en Gipuzkoa. Siglos XV-XVIII, San Sebastián, Diputación Foral de Gipuzkoa, 2008.

MORALES SOLCHAGA, E., Los gremios artísticos en Pamplona durante los siglos del Barroco, Pamplona, Gobierno de Navarra, 2016.

MORALES SOLCHAGA, E., "The constitution of Cadiz and the dissolution of the guilds. El caso de los plateros pamploneses", in Príncipe de Viana, nº 256 (2012), pp. 761-781.

NÚÑEZ DE CEPEDA Y ORTEGA, M., Los antiguos gremios y cofradías de Pamplona, Pamplona, Imprenta Diocesana, 1948.

ORBE SIVATTE, M., Platería del taller de Pamplona durante los siglos del Barroco, Pamplona, Gobierno de Navarra, 2008.

VV.AA., Catalog Monumental de Navarra, Vol. V*** [Pamplona], Pamplona, Príncipe de Viana, 1997.