The piece of the month of February 2020

A RELIEF OF THE HOLY KINSHIP (1561) BY MIGUEL ESPINAL I, APPRAISED BY JUAN DE ANCHIETA

Ricardo Fernández Gracia

Chair of Navarrese Heritage and Art

University of Navarra

The church of the Dominicans of Pamplona preserves a relief of the Sacred Parentage of the Virgin, made in 1561 by Miguel de Espinal I, an image maker from Villava, for the disappeared altarpiece of the Virgin of the Rosary and reused on the bench of the altarpiece of Our Lady of Nieva or Soterraña, since 1734. The iconographic topic , frequent in northern Europe at the end of the 15th century, and even in the first half of the 16th century, would be practically banished as inappropriate after the Council of Trent, when every effort was made to provide historicity and ownership to the images that were exhibited before the faithful. It is a unique example in Navarre of a very exceptional topic in the Spanish panorama.

Relief of the Holy Parentage in Dominicos de Pamplona,

by Miguel de Espinal I, 1561. Photo: J. I. Riezu.

Added to the iconographic interest of the piece is the vindication of its author, until now confused with the homonymous sculptor of the Ochagavía altarpieces, as well as the appraisal final of the work by the famous Juan de Anchieta, in 1572, in what was his first activity in Navarre, until now unpublished. Documents from the Navarrese Royal Courts have helped us to clearly outline the chronology of the piece, its artists and various circumstances surrounding its execution and first polychrome process.

The author of the relief: Miguel de Espinal I, sculptor from Villava, died around 1564.

Father Fausto Andía gives us an account of the origin of the relief in his history of the convent of Santo Domingo de Pamplona, written in 1751. When dealing with the altarpiece of the Virgin of Soterraña, made in 1734 at the initiative of the mayor of Court Don Jose Ezquerra, he affirms that the images of the same one and its medal - with that name is denominated the relief historian - were proper of the convent, for having belonged to the old altarpiece of the Virgin of the Rosary. The aforementioned chronicler points out textually that those pieces "were previously in the old altarpiece and were only retouched or cleaned", when they were placed in the altarpiece of the Soterraña.

New data extracted from unpublished documentation of some processes litigated in the Navarrese Courts inform us that the author of the set was Miguel de Espinal I, a sculptor from Villava, married to Juana de Iribas, who was being confused with his namesake, the author of the Ochagavía altarpiece, who died in 1586 and married Catalina Beauves in 1575. To distinguish between them, we call them I and II, respectively, following a chronological criterion.

The first of these, who lived in Villava and died in 1564, was responsible for the sculpture of the altarpiece of San José in Pamplona Cathedral (1560), documented by Eduardo Morales, as well as the altarpiece of Maquirriain and a stone cross next to the bridge of Lumbier, made in 1553.

The gilding and polychromy of the old Pamplona altarpiece of the Rosary was contracted, in 1577, with four painters: Antonio de Aldaz and his son, Sancho de Lumbier and Pedro de Alzo y Oscáriz, so that each one of them would do position of different parts of the piece. The polychromy of the great relief "of average carving" would run to position of Pedro de Alzo, within a year and a half. All that work was lost in 1734, when in fact the whole set was re-polychromed, frustrating the unity with the sculpture.

Valuation by Juan de Anchieta, for the first time in Pamplona in 1572.

Disagreements about the value of the altarpiece, which included the relief in question, arose between the different appraisers in 1562, as they estimated it at 289, 230 and 283 ducats, which suggested a final valuation that, for the time being, was not made.

After the death of its author, Miguel de Espinal I, his widow, Juana de Iribas, sued the confreres of the Rosary for what remained to be collected from her husband. A long process, litigated from 1570 and prolonged by the successive appeals of the parties, ended with a new and final appraisal entrusted to none other than Juan de Anchieta, on behalf of the confraternity, and Miguel de Espinal II, by the aforementioned widow, which seems to indicate a kinship with her late husband, with the same name and surname.

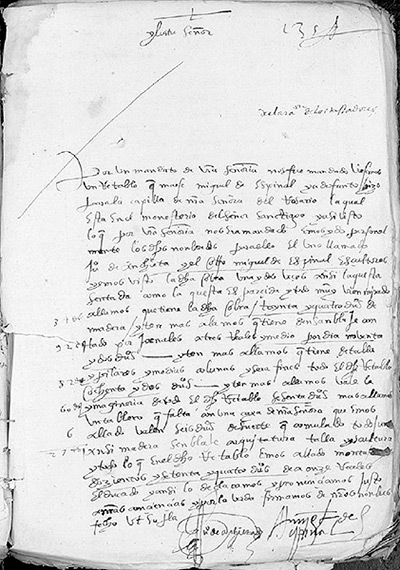

Appraisal of the altarpiece of the Rosary of the Dominicans of Pamplona, by Juan de Anchieta and Miguel de Espinal II in 1572 (AGN. Process no. 097981, fol. 135).

This is the first time that Anchieta is documented, in 1572, in Pamplona, a city where he was known to have been sporadically before his definitive establishment there in 1577. The appraisal document is twofold; one simple, signed by the artists, and the other, more complete, witnessed before a notary. The content of both documents is exceptional for the detail with which they value the different parts of the altarpiece: wood, assemblage, decorative carving and sculpture. The price of the wood was estimated at 34 ducats, the assembly at 92 ducats, at the rate of three and a half reales for eight months -each month with 24 working days-, the carving of columns and panels at 82 ducats and the imagery at 60 ducats, in addition to other small amounts. The final amount came to 274 ducats, an amount that was closer to the first appraisal of 289 made by Pedro Moret and Miguel Gárriz ten years earlier. The bodies of the altarpiece are called "hiladas", describing all its elements with terminology of the time. The relief that concerns us is described as follows: "in the same row and in the middle of it there is a large carved history of walnut wood imagery, more relieved that average carving, and measured and looked at each figure by itself and all board said they had to estimate and estimated at 30 ducats". If we take into account that the figures of average carving of different parts of the altarpiece were valued at four and a half ducats each, the price of the relief at thirty ducats, with seven figures of children and 10 of characters, some only half-bodied, is proportional to the rest of the sculpture.

Relief characters

It is strange, to say the least, that a relief of heterodox iconography should be reused in 1734. On the one hand, because it was located in a church of an eminently intellectual order and seat of the University of Pamplona, and, on the other, because it was in plenary session of the Executive Council Century of the Enlightenment. It is possible that the choice of the topic in the 16th century and its conservation was influenced by the textual source , the work of the Dominican friar Jacobo de la Voragine, as we will see later on. In this regard, we must remember that, among the very few works with the iconographic topic preserved in Spain, the fresco of the Vázquez de Molina palace, which was a Dominican convent in Úbeda, stands out, dated in 1595 and Pass for the meditation on the triumph of the woman in the lineage of Jesus and her relevance in the beginnings of Christianity, through the great matriarch Saint Anne.

The identification of the figures without a phylactery has given rise to misunderstandings, with the two figures accompanying Saint Joachim being thought to be the prophets Isaiah and Daniel, something that must be ruled out in the light of the texts and even of various graphic sources such as the engraving by Lucas Cranach. Likewise, the figure of Alpheus, the father of the four children and husband of Mary Cleophas or Jacobé, has been erroneously identified as a prophet.

The seventeen characters of the iconographic topic appear in the large rectangular relief. In the center, St. Anne triplex, group composed of the aforementioned saint with her daughter the Virgin Mary and the Child Jesus. Next to the main group we find, on one side, St. Joseph accompanied by a phylactery with his name and, on the other, St. Anne's three husbands: St. Joachim, with his phylactery, Cleophas, older, and Salome, younger and third consort. In the lower part of the composition we find two family groups: on the left, Mary Cleophas or Jacobé with her husband Alpheus and her four sons, identified by their inscriptions (Philip, Jude, James the younger and Simon); on the right, the other half-sister of the Virgin, Mary Salome, with her husband Zebedee and her two crowned sons: Saint John the Evangelist and James the elder, identified by their attributes, the first with the cup of wine poisoned with the serpent and the second with the gourd of the pilgrims.

As we will see, all the characters coincide with what is narrated in the textual sources, with the only exception of one of the children, son of María Jacobé and Alfeo, who is identified with Saint Philip, instead of with Joseph the Just, probably because his text was repainted and the design of the cartouche was reworked. This was not the only modification made in 1734 when repolychroming the piece, since the phylacteries corresponding to the second and third husbands of Saint Anne were eliminated, as evidenced by the re-drawing of the entire area, as well as the handwriting of the cartouche of Saint Joachim, similar to that of the other inscriptions that barely respect the old spellings, except in that of Saint Joseph.

The topic in the light of Leyenda Dorada and other medieval texts.

The seventeen characters make up the story of the family of St. Anne, the mother of the Virgin if we follow the textual source par excellence, the Golden Legend. Its author, Jacobus de la Voragine, Dominican and archbishop of Genoa, compiled in the middle of the 13th century the lives of about one hundred and eighty saints and martyrs from the Gospels, the apocrypha and other texts. That anthology was initially called Legenda Sanctorum and was one of the most copied books during the leave Age average, currently counting more than a thousand incunabula copies.

The part corresponding to St. Anne includes the account of her three husbands, which, as L. Réau observed, does not agree with her long sterility before conceiving Mary. The text of Jacob de la Voragine reads as follows:

According to tradition, Anna married three times and had three successive husbands, Joachim, Cleophas and Salome. From the first of them, that is, from Joachim, she begot Mary, the mother of the Lord, who, as time went by, was given in marriage to Joseph and begot and gave birth to Our Lord Jesus Christ. When Joachim died, Anna married Cleophas... from this second marriage she had another daughter to whom she also gave the name of Mary, this Mary later married Alpheus and from this marriage were born four sons who were James the Less, Joseph the Just, popularly known by the nickname of Barsabbas, Simon and Judas. When Cleophas died, Anna married Salome and with this, her third husband, she had a daughter to whom she gave the same name as the other two, Mary. This third Mary married Zebedee and with him she had two sons who were James the Greater and St. John the Evangelist.

At the beginning of the 15th century, the Franciscan tertiary nun and restorer of the Poor Clares, Coleta de Corbie (1381-1447), had a vision of St. Anne confirming that legend. Other authors who picked up the story, without refuting it, were the medieval theologians and philosophers Hugo de San Víctores, Pedro Comestor, Leopoldo Cartujano and Juan Gerson.

Important examples of topic can be found in engraving, painting, tapestry and sculpture in the Netherlands, Germany and northern France. We will cite, by way of example, some outstanding works. Anonymous sculptural reliefs are relatively abundant, although it is true that sometimes the characters are reduced or enlarged. Something similar occurs with the engravings, among which are those of Dürer (1511), Lucas Cranach (1509-1510) and an anonymous one (1495-1500) in the British Museum. Painted representations include a large number of examples (Quetnin Metsys, Jörg Breu, Derick Baegert, Jan Baegert, Wolf Traut, Simon de Chalons, Jan van Caninxloo). According to L. Réau, the Santa Parentela is a clear precedent of the so-called "family portraits", a triumphant genre from the Renaissance onwards, but hardly developed in the Middle Ages average.

Woodcut of the Holy Parentage by Lucas Cranach the Elder (1509-1510),

from the British Museum.

The post-Tridentine critique of topic and its demise

As is well known, most of the topics that lent themselves to confusion or false doctrine were eliminated in the context of the application of the 1563 decree of the Council of Trent, concerning images, which stipulates:

Let the bishops diligently teach that by means of the stories of the mysteries of our redemption, expressed in pictures and other images, the people are instructed and confirmed in the articles of faith, which should be continually remembered and meditated upon, and that from all sacred images great fruit is drawn, not only because they remind the faithful of the benefits and gifts that Jesus Christ has granted them, but also because the miracles that God has worked through the saints and the salutary examples of their lives are placed before the people, so that they may give thanks to God for them, conform their lives and customs to imitate those of the saints, and be moved to love God and practice piety.

In the same Council, it was forbidden to place

in the churches images which are inspired by erroneous dogma and which may confuse the simple in spirit; it further desires that all impurity be avoided and that the images not be given provocative characters. To ensure the fulfillment of such decisions, the Holy Council forbids the placing in any place and even in churches that are not subject to the visits of the common people, of any unusual image, unless it has received the approval of the bishop.

From then on, orthodoxy, decorum, propriety, historicity, rigor of the sources and clarity of the message were put into action by the pastoral visits of the bishops, the synodal constitutions of the different dioceses and some books with safe precepts for artists and patrons, since the defense of the images played a crucial role in the development of post-conciliar sacred art. Among the texts are the Dialogi sex ( 1566) by Nicholas Harsfield; De typica et honoraria sacrarum imaginum adoratione ( Louvain, 1569), by Nicholas Sanders; the Discorso intorno alle imagini sacre et profane, by the Archbishop of Bologna G. Paleotti; De picturis et imaginibus sacris (Louvain, 1570) by Juan Molano; and Della Pittura sacra by Federico Borromeo (Milan, 1624).

In his aforementioned work, Molano dealt with the sacred generation and censured the inappropriateness of that representation. St. Peter Canisius, Jesuit and theologian, Cardinals Bellarmine and Baronius, as well as the Dominican Melchior Cano and the Jesuit Francisco Suarez also refuted the fanciful story and its images. One of the most erudite texts of historical-theological criticism on the topic is found in the grade thirty-fifth of the first part of the Mystical City of God, by Mother Agreda, written with great erudition by the Franciscan friar José Ximénez de Samaniego.

Francisco Pacheco, Velázquez's father-in-law and author of The Art of Painting (1649), wrote in this regard: "At one time the painting of the glorious Saint Anne seated with the Blessed Virgin and her son in her arms, and accompanied by three husbands, three daughters, and many grandchildren was very valid: as in some old prints it is found. Which today the learned do not approve of, and it should be done justly by sane painters...".

As a consequence of all this, the topic of the three Marys and the holy kindred ended up disappearing due to the rejection of the ecclesiastical authority, since it was considered compromising for the report of St. Anne, who was declared to be without stain, like the Virgin.

SOURCES AND BIBLIOGRAPHY

file Royal and General of Navarre. Royal Courts. Case No. 066802. Miguel de Espinal, carver, neighbor of Villava, against the brotherhood of Nuestra Señora del Rosario of the convent of Santiago de Pamplona, regarding execution for 289 ducats for the construction of an altarpiece (1562). Process No. 097981. From Juana de Iribas, widow of Miguel de Espinal, a resident of Villava against Miguel Caparroso and others, prior and elders of the brotherhood of the Rosary of Pamplona, regarding compliance with sentences related to the payment of 110 ducats for an altarpiece (1570-1573). Process No. 086521. From Miguel de Espinal, carver, neighbor of Villava, against the town of Lumbier regarding the payment of amounts for the carving of a stone cross (1556). Case no. 1193297. Pedro Alzo y Ozcáriz, Sancho de Lumbier and Martín and Antonio Aldaz, painters, residents of Pamplona, against the convent of Santiago de Pamplona (Dominicans), Pedro Aoiz, Juan López de Azteráin and others, prior and majors of the brotherhood of Nuestra Señora del Rosario founded in said convent, regarding payment of 300 ducats of salary for painting the altarpiece of Nuestra Señora del Rosario (1582). Process 251434. Graciana de Zabalegui, usufructuary widow of Miguel de Aldaz, painter, neighbor of Pamplona, against the brotherhood of the Rosary of the convent of Santiago de Pamplona (Dominicans), regarding the appointment of arbitrators to regulate the cost of the construction of an altarpiece and payment of the estimated amount (1583).

ALMANSA MORENO, J. M., "Las pinturas murales del palacio Vázquez de Molina de Úbeda", bulletin de programs of study Gienneneses, núm. 186 (2003), pp. 45-81.

BIURRUN SOTIL, T., La escultura religiosa y Bellas Artes en Navarra durante la época del Renacimiento, Pamplona, Gráficas Bescansa, 1935.

FERNÁNDEZ GRACIA, R., "Heritage and identity (24). A relief full of history on the legend of Santa Ana: three husbands, three daughters and seven grandchildren", Diario de Navarra, January 17, 2020, pp. 56-57.

GARCÍA GAINZA, M.ª C. et al., Catalog Monumental de Navarra. V. Merindad de Pamplona***, Pamplona, Government of Navarra - Archbishopric of Pamplona - University of Navarra, 1997, pp. 235-235.

GARCÍA GAINZA, M.ª C., "Miguel de Espinal y los retablos de Ochagavía", Príncipe de Viana, no. 108-109 (1967), pp. 339-351.

MÂLE, E., El Barroco. Religious art of the 17th century. Italy, France, Spain, Flanders, Madrid, 1985, p. 27.

MOLANUS, J., Traité des Saintes Images, Introduction, traduction, notes et index par F. Boespflug, O. Christin and B. Tassel, vol. I, Paris, Cerf, 1996, pp. 412-414.

MORALES SOLCHAGA, E., "El gremio de San José y Santo Tomás de Pamplona hasta el siglo XVII", Príncipe de Viana, no. 239 (2006), pp. 791-860.

MORENO CUADRO, F., "La Santa Parentela", bulletin del Museo e Instituto Camón Aznar, no. 54 (1963), pp. 5-24.

PACHECO, F., El arte de la pintura, Edition, introduction and notes by B. Bassegoda i Hugas, Madrid, Chair, 1990, p. 580.

RÉAU, L., Iconography of Christian Art. Iconography of the Bible. Nuevo Testamento, t. 1, vol. 2, Barcelona, Ediciones del Serbal, 1996, pp. 147-153.

SALVADOR Y CONDE, J., "Historia de Santo Domingo de Pamplona. Códice inédito del P. Fausto Andía", Príncipe de Viana, nos. 148-149 (1977), pp. 513-569.

SEBASTIÁN, S., Counter-Reformation and Baroque. Lecturas Iconográficas e iconológicas, Madrid, Alianza, 1981, p. 62.

VORAGINE, S. de la, La leyenda dorada, translation by Fray José Manuel Macías, vol. 2, Madrid, Alianza, 1982, pp. 565-575.

XIMÉNEZ SAMANIEGO, J., "Notas a esta primera parte de la Historia de la Vida de la Madre de Dios...", in María Jesús de Ágreda, Mística Ciudad de Dios, vol. I, Madrid, Imprenta de la Causa de la Venerable Madre, 1765, pp. 169-17.