The piece of the month of July 2020

SEPULCHRAL TOMBSTONE OF THE PARISH CHURCH OF SANTIAGO DE GARDE

José Ignacio Riezu Boj and Cristina Bozal Viguria

University of Navarra

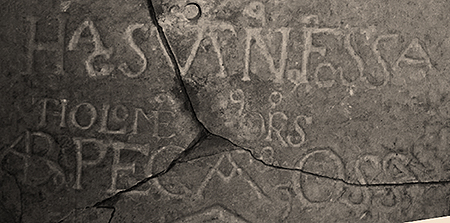

In 2009, while repairing the floor of the parish church of Santiago de Garde, in the Roncal valley, the tombstone that we now present (fig. 1) was found. It is a rectangular slab of approximately 78 x cm (we have only been able to have access to its study through the photographs taken after its finding by Mr. Pedro framework, who has kindly lent them to us). In the process of extraction the tombstone was broken into several fragments, as can be seen in the photographs. At present it is under the new wooden pavement placed after the works.

Tombstone of the parish church of Garde.

To describe the engravings and registration we have divided the tombstone into four parts. The first quarter presents a relief with two crossed bones, in the shape of an X, inside a rectangle of about 16 x cm that presents a curious motif on both sides. In the second quarter there is a registration that occupies three lines. In the third quarter there is a very simple relief that could correspond to a mitre or hood. Finally, in the last quarter the motif of the first quarter is repeated, with two crossed bones in X the interior of a rectangle.

Reading of the registration

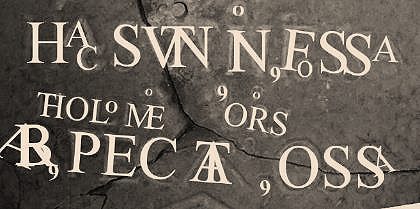

As we have mentioned, in the second quarter of the slab there is a registration in capital letters that occupies three lines (fig. 2). The height of the letters of the first and last line (6 cm approximately) is twice the height of the letters of the central line. It should be noted that this line is closer to the last line than to the first and does not start at the same height as the other two, but has a small indent.

Tombstone of the parish church of Garde, detail of the registration.

It is an elegant and neat Latin registration in square capital, with letters of regular height. The epigraph presents an elaborate and complicated succession of letters, some linked, others interlocked, also superimposed and even with different sizes and at different heights. There are also large interpunctuation signs in the form of 9's. All these artifices make it confusing to read. The registration has no abbreviations.

Next, we will read the registration. The first word is "HAC" in which the H, exempt, occupies the entire height of the line, followed by the A, which only occupies the upper half, and the C which, linked to the A, occupies only the lower part of the row. The second word "SUNT" is more confusing to read because, although the S is isolated, the V, N and T are superimposed, occupying the entire height of the line and coinciding with a large fracture of the tombstone, which makes it difficult to read. The N is intuited, but, in any case, it would be upside down. The next word is "IN", the I is superimposed on the first vertical stick of the N, although it is easily identified by the dot that appears above the line. The last word in this row is "FOSSA". All the letters are exempt. The F and the two S's occupy the full height of the line, while the smaller O is recessed within the lower part of the F, and the smaller A is in the upper half of the line. It should be noted that between "SUNT" and "IN" and between "IN" and "FOSSA" there is an interline punctuation mark in the lower part of the line in the form of a 9. As we will see below, the central line (which we will call auxiliary) is an artifice of the epigrapher to finish some words that he cannot insert in the last line. In this line, the first word is "cafeteria(THOLOMEI)". The first three letters, "cafeteria", are at the beginning of the line. The A is linked to the B, rotated a little to the left in order to link well with the B. The B is in turn superimposed on the A. In turn the B is superimposed with the R, of which only the tail protrudes from the lower curve of the B. Surprisingly, the word continues in the central line, just above the B and the R with the letters "THOLOMEI", smaller than those of the last line. In it the T and H are linked, the second O is embedded in the L and M, E and I are linked, the I being distinguished by the dot protruding from the line. To read further we must go down to the last line, where, separated by a barely visible interpunctuation sign below the tail of the R, is the following word "PEC(C)AT(ORIS)," which, like the previous one, is divided between the last line and the auxiliary. "PECAT" in the bottom line and "ORIS" in the auxiliary. Only the T (only perceptible through the upper crossbar) and the A are superimposed in the lower part, while in the upper part it is the R and the I that are superimposed. The A for "PECAT", which occupies the geometric center of the tombstone and to which the engraver seems to have wanted to give a special importance. The letter is wider than the rest of the letters and has the crossbar divided in two, in the shape of a V. The last word of our registration is "OSSA" which is separated from the previous one by another interpointing sign in the shape of a 9. This time the first three letters are exempt and occupy the entire height of the line, while the last A, smaller than the others, is placed over the last S and rotated 45 Degrees to the left.

It is necessary to emphasize the great amount of epigraphic resources used by the lapicide in all the words: superimpositions, boxings, links, rotations, changes of size and position, continuation of the word in the upper line, interpunctuations, etc. There is not a single word in which he has not used any of these resources. The invoice of the letters is careful, and that of the lines, although it leans a little downward, is quite regular; the words are correctly written, except for the geminate of pec(c)atoris, which is simplified.

Summarizing all that has been said so far, the registration of the tombstone of Garde reads "HAC SUNT IN FOSSA / BARTHOLOMEI PECATORIS OSSA", which translated means IN THIS PIT ARE / THE BONES OF THE SINNER BARTOLOMEO.

About the formula

The formula used is very frequent in funerary epigraphy, with some variants for the beginning: "hic situs est...", "hic iacet...", "hoc tenet...", "hic cubat..." of which we have numerous examples throughout history. Some peninsular examples are the tomb of Queen Elvira, wife of Alfonso V of León in the Pantheon of Kings of San Isidoro de León, year 1022: "...HAC IN FOSSA GELOIRAE REGINAE PULVIS ET OSSA...". In the epitaph of Count Malgrediense in San Zoilo in Carrión de los Condes (Palencia), year 1131: "PULVIS IN HAEC FOSSA PARITER TUMULANTUR ET OSSA CONSULIS ILLUSTRIS FERNANDI MALGRADIENSIS...". The tomb of Guicardo de Buxa, prior of Santa Maria de la Bloise (France), buried in San Miguel de Escalada (León), year 1169: "President DE BUXA CONTEMPNENS OMNIA FLUXA PAUSAT IN HAC FOSSA CAPIENTI CORPUS ET OSSA...". The tomb of the bishop of Osma and archbishop of Toledo Rodrigo Jiménez de Rada, year 1247: "...CONTINET HOC FOSSA RODERICI CORPUS ET OSSA...". The sepulchral epitaph of Doña Jacometa of Hungary, companion of the queen of Aragon Violante, in the chapel of San Juan Bautista de Santa María la Real de las Huelgas (Burgos), year 1259: "ISTA VORAX FOSSA IACOMETE CONTINET OSSA...". Or the tomb of friar Pablo Miracle in the cloister of the monastery of Santes Creus (Tarragona), year 1713: "...FACENT IN HAC FOSSA MIRACULI NATURAE OSSA UT ALTER".

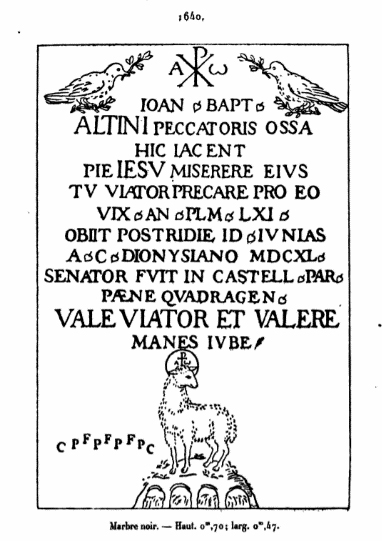

Tombstone in the Church of Saint Severin in Paris.

The use of pec(c)atoris (sinner) to refer to the deceased is striking. It is not very common, because some positive adjective is usually used (praesulis, insignis, nobilis, venerabilis). Perhaps it is because the deceased himself left the epitaph specified, perhaps out of humility. Nevertheless, this formula can be found in some European ecclesiastical epitaphs of the 17th and 18th centuries as in the 1640 epitaph of Jean Baptiste Altin in the Church of Saint Severin in Paris: "IOAN BAPT / ALTINI PECCATORIS OSSA / HIC JACENT / PIE JESU MISERERE EIUS / TU VIATOR PRECARE PRO EO / ..."(fig. 3), the 1715 epitaph of the bishop of Andria in Italy: "EN NICOLAI ADINOLFI NEAPOLITANI, EPISCOPI ANDRIENSIS TER MAXIMI PECCATORIS OSSA", or the 1760 epitaph of the church of Santa Fosca in Venice: ZACCARIAE VALLARESSII PATRITII VENETI MISERIMI PECCATORIS OSSA 1760".

But the registration most closely related to our tombstone is the famous epitaph of the English saint Bede the Venerable. This monk, theologian and scholar of the 7th century (ca. 672-735) is buried in the cathedral of Durhan (England) with a tombstone engraved with a simple registration. This epitaph became popular and traveled throughout Europe thanks to the halo of mystery surrounding its creation. As narrated in The Golden Legend, upon the death of Bede, a very devoted member of the clergy wanted to write a verse on his tomb. After much pondering, he composed the following stanza: HAC SUNT IN FOSSA, BEDAE SANCTI OSSA, but that did not fit the Latin rhythm of the verse. After much thought without finding the solution, he fell asleep, and the next morning when he approached the tomb he found that an angel had engraved the registration, which read: HAC SUNT IN FOSSA BEDAE VENERABILIS OSSA.

Metric of the registration

The epitaph of Bede the Venerable is a Latin verse called dactylic hexameter with leonine internal rhyme. Let us briefly explain some of these terms in order to understand registration. The versification or rhythm of classical languages, such as Greek or Latin, is based on the quantity (the duration of the syllables) and not on the intensity (the force with which each syllable is pronounced), the issue of syllables or the rhyme, as in Spanish. The hexameter verse consists, as its name indicates, of six meters or feet (unit of classical metrics). The dactyl is a meter of 4 beats, which could be dactylic (succession of three syllables: long, brief, brief) or spondean (long, long). In classical metrics the 5th foot of the hexameter had to be a pure dactyl (long, short, short). In addition, classical dactylic hexameters usually had at least one pause (also called caesura) after the 5th half-foot or after the 7th half-foot, which usually coincided with the end of a word. These pauses could give rise to an internal rhyme, or leonine rhyme, between the two parts of the line, rhyming the syllable before the pause and the final syllable of the line. This rhyme was very often used in medieval Latin metrics.

We will now study the metric of our registration. The author, imitating Bede's registration , wants to construct a dactylic hexameter. In fact, the first line of the registration coincides exactly with the first part of Beda's verse and ends with the pentameter caesura (HAC SUNT/ IN FOS-/SA//) after the fifth half-foot. So far so perfect. When adding the second part (cafeteria/-THOLOME/I PEC-/CATORIS /OSSA) our engraver encounters problems: there are too many syllables. Why does this happen? The use, in epitaphs, of established formulas was generalized, in which only the name and the adjective referring to the deceased had to be replaced. The personalization of our registration, by introducing in the formula the name and adjective of the deceased in genitive, both too long, caused the appearance of an excess of syllables and the destruction of the hexameter verse.

In addition, the employment of these long words not only caused a metrical problem, but also a physical conflict due to lack of space on the tombstone. This physical problem meant that the classic verse had to be divided in two (we will talk about the three lines later). But the author does not seem to be worried, since this division emphasized the rhyme between the two words with which the two lines end: "FOSSA" AND "OSSA"; a rhyme which, as we have already mentioned, was originally an internal rhyme, and which here seems to be transformed into two verses of Castilian meter, with the rhyme at the end of each line. We think that all these problems are related, not only to the space of the tombstone, but also to the engraver's lack of understanding of classical metrics. There is no longer an awareness of quantity, nor of dactylic rhythm, so fossa and ossa stand out, no longer internal rhyme, but rhyme at the end of the two lines, in the use of Spanish meter.

Problems with font size

The author of the registration uses a rather large capital letter subject which forces him, as we have already said, to divide the verse into two main lines. Despite this and the use of several common resources in his work such as overlapping, boxing, link, rotation, change of size or position of the letters, the problem of space remains, especially in the second part of the verse. To solve this conflict, the lapicide added an auxiliary line above the last line. He uses this extra line, not to subdivide the remaining phrase, but to fragment the name and adjective of the deceased and place part of the fragments in this auxiliary line. In order for the experienced reader to understand this artifice, the author used a smaller font size for the auxiliary line, placed it closer to the last line and began it with an indentation (fig. 4). Thus, to make the reading correctly once read the first line, we have to continue the reading in the last line that begins with "cafeteria", go up to the auxiliary line and finish reading the name "THOLOMEI", go back down to the second main line and read the beginning of the adjective "PECAT", again go up to the auxiliary line where the adjective ends with "ORIS" and finish the reading going down to the lower line where we read "OSSA".

Tombstone of the parish church of Garde, detail of the registration. Reinterpretation.

All these skills in the construction of the registration denote the presence of a professional in these arts, who has already lost the clear notions of classical metrics and who sacrifices clarity in reading to increase the font size. He solves the problems caused by these decisions with great skill, using many of the resources that epigraphy allows him, curiously without using abbreviations. This way of working fits in with the modes and aesthetics of the Baroque, which tries to break with the simplicity and clarity of the Renaissance to enter into the decorative complexity, artificiality, dramatism and mystery of the Baroque.

Engravings

The slab we are studying, in addition to the central registration , presents a series of engravings. In the first and last quarter that divide the slab, two crossed bones are observed inside a rectangle that sample on the sides what seems to be a double handle. It could represent an ark or a stretcher on which the body of the deceased is deposited. Finally, in the third quarter there is a very simple relief that could correspond to a mitre or a hood (fig. 5).

Tombstone of the parish church of Garde. High contrast photography.

The presence of bones as a symbol of death is very abundant in tombstones. It already appears in the Christian catacombs. For example, in the tomb dated 1619 of graduate Martín Eusa of the committee Real de Navarra and his wife in the chapel of the Holy Trinity in the church of San Saturnino in Pamplona (fig. 6), two crossed tibias and a skull can be seen in the center, surrounded by the family coats of arms.

Tombstone of graduate Martín Eusa and his wife in the chapel of the Holy Trinity in the Church of San Saturnino in Pamplona.

Bartholomew

Who could this Bartholomew be, buried in this grave?

We believe that the most logical thing is to think that our deceased is some ecclesiastic of the parochial chapter of Garde. In the XVI and XVII centuries the Garde chapter was formed by a President called abbot and by six beneficiaries who were in charge of helping the abbot. Our tombstone probably belonged to one of the abbots of Garde. Analyzing the lists of abbots of the town of Garde listed in La Villa de Garde en el Valle de Roncal ( pp. 110-111), a book written by its parish priest Javier Gárriz in 1923, we can locate up to three abbots with that name, all three with the surname Gayarre. They are listed below (for better identification we have added numerals) and the dates of their term of office as abbot or parish priest of Garde according to Gárriz are shown in parentheses:

-

Bartolomé Gayarre I (1628-1652),

-

Bartolomé Gayarre II (1653-1660) and

-

Bartolomé Gayarre III (1724-1752)

We can deduce that all these abbots with the same name and the same surname were originally from Casa Gayarre. It is very common for a name to be repeated from generation to generation among the members of the same family. This house still exists in Garde and for several centuries belonged to one of the powerful and influential families of the town. We propose as a hypothesis that one of these three abbots was the addressee of this tombstone. According to José Luis Sales,

During the Age average the corpses were buried in the cemetery, attached to the church on its main façade. At the end of the 16th century, burials began to take place inside the church. Normally the graves were family property: each family could have a maximum of three; they were usually distributed in rows, headed by those of priests and clergymen. During the liturgical services, the mistresses of each house would sit on the family tomb, placing the wax and carrying the offerings.

In agreement with the explanations of this author, in the Catalog of the file Diocesan of Pamplona we have found the annotation of a lawsuit dated in 1618 between the neighbors of the town of Garde and Bartolomé Gayarre, chaplain of His Illustriousness and his family, neighbors also of Garde, for having obtained the latter a degree scroll of burial in the first row of the church of Garde. Could it be our burial place? Although we do not know the date of the placement of the tombstone, could it be the death of the first abbot of this name in 1652?

Thinking that in the will of these abbots of Garde could appear some clue about the tombstone, we have looked for their wills in the file Real y General de Navarra in the section of notarial protocols. We have only found the will of Bartolomé Gayarre II, who succeeded his uncle Bartolomé Gayarre I in the position . We can deduce that he died young (March 7, 1660), since he was in the position only 7-8 years and in his will he left as universal heir his father Pedro, and in his absence, his mother Úrsula López, from which we can deduce that when he made the will 20 days before his death, his parents were still alive. It seems that he had a well-to-do economic position, since he left several orders among which he ordered to make an altar to Saint Michael and Saint Bartholomew, to give money to the 4 hermitages of the town or 100 reales to his maid, and he left his Library Services and his clothes to his brother Domingo. But in the testament there is no accredited specialization some to the burial and its cover. Could the parents as heirs have decided to make this tombstone in report of their son, abbot of Garde and died prematurely? This is a conjecture that will have to be proved.

We have not located the will of his uncle Bartolomé Gayarre I, but from documentation located in the Catalog of the file Diocesan of Pamplona this abbot also seems to have had purchasing power. In the Catalog we have found that he founded a chaplaincy and that he had donated a silver cross with relics to ward off clouds. Either of the first two abbots could have been the recipients of this tombstone.

SOURCES AND BIBLIOGRAPHY

DEL HOYO CALLEJA, J. (2008). "Carmina Latina Epigraphica Medievalia de San Miguel de Escalada (León)", Studia Philologica Valentina, 11, 2008, pp. 201-224.

GARCÍA LOBO, V. "El difunto reivindicado a través de las inscripciones", in IX conference Científicas sobre Documentación: la muerte y sus testimonios escritos, Madrid, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, 2011, pp. 171-198.

GARCÍA MORILLA, A. "Las inscripciones medievales de la provincia de Burgos: siglos VIII-XIII". thesis doctoral dissertation, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, School de Geografía e Historia, department de Ciencias y Técnicas Historiográficas y Arqueología. Directors: Javier de Santiago Fernández and M.ª Encarnación Martín López, Madrid, 2013. .

GÁRRIZ, J. "La Villa de Garde en el Valle de Roncal", 1923.

MIRANDA GARCÍA, F. "Carolingian authors in the Hispanic codices (IX-XI centuries). Un essay de interpretación", Studia Historica, Historia Medieval, 33, 2015, pp. 25-50.

SALES TIRAPU, J. L. "Breve vocabulario", in Catalog del file Diocesano de Pamplona, 1 (Sección de Procesos, 1559-1589), Pamplona, Institución Príncipe de Viana, 1988, pp. 437-442.

SALES TIRAPU, J. L. and URSÚA IRIGOYEN, I. Catalog de la Sección de Procesos del file Diocesano de Pamplona, 10, 1993, p. 204, document 858; and 23, 2004, p. 95, document 320.

SOLANA DE QUESADA, A. "25- Beda el Venerable and the Jacobean burial", in blog Tradición Jacobea, 2018. (accessed February 15, 2020).

VELÁZQUEZ, I. "Tituli metrici de época visigoda y altomedievales: aproximación a sus tópicos y conexiones literarias", conference proceedings I congress Nacional de Latín Medieval (León 1-4 Dec. 1993), León, 1995, pp. 387-394 (cfr. p. 389).