The piece of the month of June 2020

A SINGULAR PICTORIAL ENSEMBLE OF THE 16TH CENTURY IN THE SHRINE OF OUR LADY OF FAIR LOVE DE ARQUIJAS DE ZÚÑIGA. INSCRIPTIONS AND GRAPHIC SOURCES

Pedro Luis Echeverría Goñi

University of the Basque Country

The exceptional nature of the Shrine of Our Lady of Fair Love of Nuestra Señora de Arquijas lies both in its Proto-Gothic walls, chancel and Wayside Cross from the first half of the 13th century and in its Renaissance mural paintings, constituting one of the few churches in Navarre that has preserved its cladding, which gives us an idea of what was a common internship in the architectural finish of all the buildings. The ribbed vaults of the first two bays, the choir and the sacristy correspond to the middle of the 16th century, unifying the two stages of the ashlar masonry, a brushstroke of false rigging (ashlar, brick and cushioned brickwork), Roman-style grotesques and candelieri (scrolls, dolphins and foliaceous masks) (fig. 1) and mural paintings, among others. 1) and mural paintings, among which stand out the scenographic Calvary of a feigned triumphal arch in front of the entrance door and the trompe l'oeil of a "painting" of the penitent Magdalene in the sacristy. If the architecture built in the 16th century continues to be essentially Gothic, the painting that adorns it not only ennobles, regularizes and modulates a coarse masonry work, but also allows it to be described as Renaissance and even Mannerist, as corroborated by the monumental serliana, semicircular arches, cornices, dentils, marbling of the columns and other classicist elements executed with the brush.

Photomontage with the brushstroke of the vault of the second section. Brick cuttings. core topic with anagram of Christ. Grotesque ordinances.

The first news about the existence of mural painting in Zúñiga is provided by a detailed reading of the first contract of 1555 for the main altarpiece of the parish. In one of its clauses on the form of payment, it is specified that the carvers would be paid 600 ducats for five years from the first fruits, not embarking on other works except "for oil and wax and things for the service of the said church and to paint the chapels of the church". Among the guarantors of Pedro de Gabiria I subscribes a Pedro de Latorre, neighbor of Estella, perhaps the friend and partner of the carver. Pedro de Latorre (c. 1525-1579) was "a very good official in this art and official document" for more than thirty years in the Kingdom of Navarre and in Castile, dedicating himself mainly to the gilding and stewing of altarpieces, although he was also a painter of "black and white". In his workshop he had servants and officials such as Juan de Miñano Mayor from Vitoria and Juan de Segura y Torre.

We think that the paintings of the Shrine of Our Lady of Fair Love must have been executed in the decade of the 60's of the XVI century, once the covers and additions were finished, probably by Tomás de Oñate I (+ 1592), an outstanding painter of the family clan of Vitoria, started by his father Martín de Oñate and continued by his half-brothers Juan I and Jerónimo de Oñate or Olazarán and his sons and heirs Tomás II and Gaspar de Narría. He was a multifaceted master who in the last third of the 16th century produced easel works, polychromy, ephemeral art and, above all, mural painting. He formed a company with Andrés de Miñano, another of Vitoria's great specialists in the art of brushwork and church painting and, as such, he was called upon by foreign masters from Navarre and Gipuzkoa to collaborate in various enterprises. Thus, we know that he was related to Pedro de Latorre and was proposed by the latter in 1567 for the appraisal of the collateral altarpieces of Allo. In addition, we have documented his presence in Santa Cruz de Campezo, where in 1568 he charged 9,000 maravedís "for painting the sacristy". Let us remember that Zúñiga shared the board of trustees of the Shrine of Our Lady of Fair Love with this town in Alava, with the two regiments (mayor, aldermen or justices) always appearing as parties in all the deeds. Finally, this possible authorship is corroborated by the demonstrated capacity of the workshop that this painter directed and the stylistic identity with several of his works. The presence of such a spectacular Crucifixion with its inscriptions in this Shrine of Our Lady of Fair Love must be related to the liturgical offices of the Holy Week triduum. This devotion to the Holy Cross, promoted by the Franciscans of the disappeared convent of San Julián de Piérola, which in 1566 had eight friars, will be concretized in the construction of the Shrine of Our Lady of Fair Love del Santo Cristo at the beginning of the XVII century and the foundation of the brotherhood of the Vera Cruz in 1690.

The Calvary is a theatrical scenography in which there is a perfect symbiosis between images and texts (fig. 2). The arrangement, gestures and interaction of the seven characters that make up this story of redemption constitute the true catechism for the illiterate (as was the majority of the rural population), while the Latin inscriptions were addressed to the clerics and served as support for the images and the preaching. Even though we have verified the literal copy of prints by Tomás de Oñate in some works such as the Flight into Egypt (Dürer) or the Lamentation over the dead Christ (M. Raimondi) of the altarpiece of Subijana de Morillas (Álava), in the present case he acts as an "exploited" painter, since he extracts and interprets characters from several engravings, above all by Albrecht Dürer, creating a different and original work. The crucified Christ does not fit with any of those made by the German artist, as it is represented very frontal and agonizing, addressing one of his last words to Dimas, and sample a short purity cloth with a small flying knot instead of the bulky fabrics that are deployed in carvings and burins. The closest resemblances we have located are in some late Gothic German woodcuts of late 15th and early 16th century missals that show similar frontal arrangement and anatomical study. Several of these features are maintained in woodcuts from the first half of the century, such as the one in the diocesan missal of Calahorra, printed in 1542 by Juan de Brocar in Logroño.

Serliana feigned with Calvario.

Both the Virgin and St. John are inspired by a Crucifixion engraved by Dürer in 1508 (Metropolitan Museum), with Mary adopting the same pensive attitude as she rests her chin on her left hand, hidden behind the drapery, while she gathers her mantle with her right; the clearest variant of the painting is the slump of her head to her left (fig. 3). The contained pain of the Mother gives way to the dramatism expressed by St. John as he contracts his face, raises his arms and joins his clasped hands towards the crucified. The painter has left us a less expressive figure with a poorly executed counterposture, a clumsy execution of the feet, more evident in the shortening of the tunic, and arms that do not reach above the head. Although she looks up, her face lacks the rictus of the print and, finally, she has modified the red mantle, which is gathered at the waist. This is certainly not the most successful version of Durerian pathos, which Panofsky relates to the St. John of Mantegna's Entombment (c. 1465-1475) and that of Grünewald's Small Crucifix (c. 1510).

Photomontage of the Virgin and St. John. A. Dürer. Crucifixion, details (Metropolitan Museum, New York).

The model for the figure of the Magdalene seems to have been taken from the carving of Dürer's Great Crucifixion (c. 1495-1498) (British Museum) (fig. 4), which, in turn, imitates one attributed to his master M. Wolgemut in which she is depicted embracing the wood. In the version of the first one, she also appears kneeling at the foot of the cross, but holding the Virgin collapsed by pain and with her head raised looking at the Crucified and a long hair loose. The painting reproduces this attitude, but the former sinner wears a luxurious and somewhat refractory dress with puffed sleeves and a headdress that reveals the ponytail; in addition, other gestural changes are introduced such as the raised arms in correspondence with those of St. John; she brings her left hand to the feet of Christ, who had anointed at the banquet in Simon's house, as a sign of adoration, while the open right hand reinforces the pathos of the scene. Among the nine hermitages listed by graduate Martín Gil in 1556, quotation is one dedicated to the Magdalene and, in addition, two other representations of the penitent saint reclining are known, the relief of the bench of the main altarpiece of the parish of Zúñiga, in correspondence with San Jerónimo, and the painting of the sacristy, a contemporary work to the one we are dealing with.

Photomontage of the Magdalena. M. Wolgemut. Crucifixion with Mary Magdalene, det. (National Gallery of Art, Washington). A. Dürer. Great Crucifixion,

det. (British Museum).

The smaller-scale thieves are popular figures dressed to differentiate them from Christ, with Gestas resembling his namesake in some late Gothic woodcuts such as a Flemish one from Ludolph of Saxony's Life of Jesus Christ of 1487. In addition to a similar clothing, he repeats the arms tied behind the crossbeam and the legs gathered in a V, drawing a serpentine line; more than by his twisting, it reflects his lack of repentance looking the other way, which does not occur in the engraving. The disposition of this thief in the engraving of Dürer's Great Crucifixion is identical, although in this case it is a young nude with a correct anatomical study. Located next to the Virgin is a soldier with spear and shield (Longinos) who acts, as recommended by Alberti in his treatise on painting, as a participatory element or narrator to introduce us into the scene.

The Latin registration that runs along the top of the arch is taken from the Vulgate, from the beginning of Jeremiah's Prayer and reads: "O VOS OMNES QVI TRANSITIS PER VIAM ATTENDITE ET VIDETE SI EST DOLOR SICVT DOLOR /MEVS", whose translation is as follows: "O all you who pass by the way, look and see if there is pain like my pain" (Lamentations 1:12). This text, included in the third lesson of the first nocturn of Matins on Holy Thursday and at other liturgical moments, was frequently interpreted with music, either in Gregorian chant or plainchant, or in polyphonic elaborations by numerous composers from the 16th century onwards. The polyphonic O vos omnes could also be an independent motet performed on Good Friday. The text, which showed the desolation of Jerusalem before the destruction of the temple by Nebuchadnezzar II, is a poetic prefiguration of the pain for the death of Christ. It is collected in the Breviarium Calagurritanum et Calceatense, printed in Logroño in 1543 by Juan de Brocar and ordered by the bishop Antonio Ramírez de Haro. We already find this same verse of the biblical verse in some relevant works of the diocese of Calahorra, to which Zúñiga belonged, such as the main altarpiece of the cathedral of Santo Domingo de la Calzada, in whose bank appears a cartouche with the registration sgraffito in gold under the relief of the Quinta Angustia (Fifth Anguish).

On both sides of the cross and above the Magdalene, who is reverently touching the feet of Christ, is distributed the registration in capital letters of greater canon that says: "BONVM/ OPVS OPER/ATA EST/ IN ME" ("He has done a good work with me", Matthew 26,10), taking up the words of the Lord in Simon's house in Galilee, in response to the disapproval of the Pharisee for having let himself be anointed with perfumes by the sinful woman, who is identified with Mary Magdalene. The sentence that appears on both sides of the cross between the Virgin and St. John, "CHARIT/AS AD/OMNIA/VALET" ("Charity is good for all things"), highlights that supreme example of love for mankind which is the sacrifice of Christ on the cross to redeem the human race. Finally, the act of acceptance and faith of the Good Thief and the response of Christ with the promise of heaven, through the words that come out of their mouths in a smaller canon than those of the other inscriptions, is staged in the upper part, as if it were a comic strip. Dismas says to him, looking at him with hope: "DOMINE MEMENTO MEI, DVM VENERIS IN REGNVM TVVM" ("Lord, remember me when you are in your kingdom", Luke 23:42), to which Jesus replies: "AMEN DICO TIBI HODIE MECVM ERIS IN PARADISO" ("I tell you the truth, today you will be with me in Paradise", Luke 23:43).

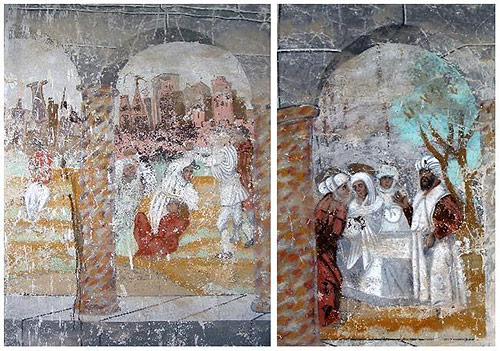

In the arch located to the left of the Calvary (right of the spectator) is represented the Miracle of the roses of Saint Casilda, which is the main scene of her hagiography. She was a princess daughter of the Moorish king of Toledo Al-Mamun, in the 11th century at the time of the Taifa kingdoms, who, being a Muslim, secretly practiced charity with the Christian captives. She is represented at the moment when her father surprises her and asks her to show him what she is wearing in her overskirt, an occasion when the loaves of bread become roses. This story emphasizes the value of works and the importance of charity, following the example of Christ on the cross, as expressed by one of the inscriptions on the central arch. They wear luxurious clothes and turbans, and the future saint wears a nimbus and is accompanied by a woman from her entourage (fig. 5). We think that the other scene may represent the Martyrdom of St. Zoilus that took place in Cordoba in the 4th century. We know that this young Christian, who appears curled up, was judged by Dacian and, after the executioner pulled his kidneys out of his back, the prefect himself took the sword and beheaded him. It unfolds before a walled city that occupies the background of the two minor arches. In the other arch, a foreshortened horseman on horseback adds depth and perspective. The origin of his devotion in Navarre is in the relics sent in the 9th century by Saint Eulogius to Bishop Wilesindo of Pamplona, who ordered the construction of a Shrine of Our Lady of Fair Love in his honor in Sansol, according to Father Moret, or in Cáseda.

Beheading of St. Zoilo. Miracle of the roses of Santa Casilda.

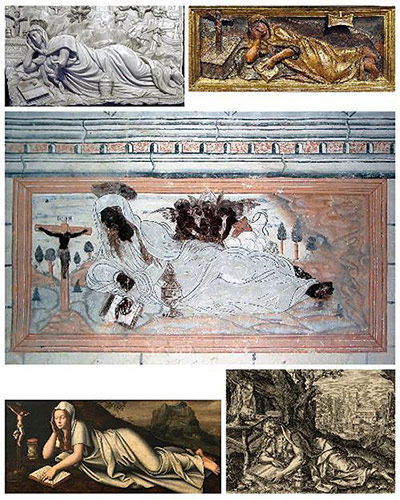

On one of the walls of the sacristy is represented in a fake framework that simulates a painting of the penitent Magdalena, topic characteristic of the Counter-Reformation that is proposed from the second half of the sixteenth century as an example of the conversion and repentance of a sinful woman. It is sample here reclining in an open landscape with naive little trees of the fourteenth century that alludes to the desert as a place of retreat from the world and in front of what could be the entrance sketched outline of a cave at her feet. In attention to decorum, all traits of sensuality always present in this iconography have been eliminated, since her body is covered by abundant fabrics of linear folds with lights and her blonde hair is covered by the turn of the mantle, also touched by the nimbus of sanctity. She is reading the paragraph of a penitential psalm that she points to in an open book, before a crucifix, and in the foreground appears her distinctive attribute, the jar of perfumes. She is accompanied by a choir of three angels on clouds holding a score and two others in the background (fig. 6). plenary session of the Executive Council The iconography was already fixed in late Gothic engravings from the end of the 15th century, and only took off with a few variations in the 16th century, with such illustrative examples as the alabaster relief of the Cartuja de Miraflores, the simpler one on the bench of the Zúñiga altarpiece, and the oil on panel (1568) by the Flemish painter Marcellus Coffermans. The Mannerist engraving most similar to this painting that we have located is somewhat later and is an invention of the Flemish painter Martin de Vos, published by E. Hooswinckel from 1580-1590, in which only the angels are missing. The blackening that today shows the naked parts of the Magdalene, Christ crucified and angels is due to the environmental conditions that have deteriorated the pigments used in the incarnations. Thus, the albayalde or lead white in the dark tends to blacken and the vermilion has turned, when exposed to humidity, to black.

Reclining penitent Magdalene. Alabaster from the Cartuja de Miraflores, Burgos (Jesús A. Sanz). Bench of the main altarpiece of Zúñiga (Pablo Corres).

Painting of the sacristy of Arquijas. Table by M. Coffermans (Museo del Prado). Engraving printed by E. Hooswinckel, from M. de Vos (British Museum).

SOURCES AND BIBLIOGRAPHY

file General of Navarra. Proceedings. Sign, 197058.

file Historical Diocese of Vitoria. Sign. 2556-2. Santa Cruz de Campezo. Libro de Fábrica I, 1511-1595, fol. 146v.

GARCÍA GAINZA, M.ª C. (dir.), HEREDIA MORENO, C., RIVAS CARMONA, J. and ORBE SIVATTE, M., Catalog Monumental de Navarra, II** Merindad de Estella, Pamplona, Institución Príncipe de Viana, 1983, pp. 773-775.

ECHEVERRÍA GOÑI, P. L., Contribution of the Basque Country to the pictorial arts of the Renaissance. La pinceladura norteña, Vitoria-Gasteiz, 1999, pp. 73-74.

PANOFSKY, E., Vida y arte de Alberto Durero, Madrid, Alianza, 1982, pp. 161-162.

CSIC Libros de polifonía hispana [accessed March 3, 2020].

I am grateful to María Gembero Ustárroz for the information on the O vos omnes catalogued so far in Spain (24), included in the database, Books of Hispanic Polyphony IMF-CSIC.