The piece of the month of November 2020

PAMPLONA 1820: THE PRINTING PRESS WITHOUT GAGS

Javier Itúrbide Díaz

Chair of Navarrese Heritage and Art

On the first day of 1820, the troops stationed in Cadiz that were about to embark, destined for the Spanish territories in America, rose up to quell the rebellion for independence that had been going on for a decade. Led by Colonel Antonio Quiroga and Lieutenant Colonel Rafael Riego, they confronted the absolute king Ferdinand VII and reestablished the liberal constitution approved in 1812 in the heat of the struggle against Napoleon. It was not a nationwide military conspiracy but an uprising -the first in a century that was to be prodigal in them- that was spreading throughout the peninsular capitals, driven by the military and seconded by the urban bourgeoisie.

At 10 a.m. on Saturday, March 11, 1820, at place of the Castle of Pamplona, the troops quartered in the city, supported by more than two hundred armed civilians, proclaimed and swore the Constitution of Cadiz in the presence of the absolutist city council and deputation, who had reluctantly joined the ceremony at the last moment. Immediately the prisoners imprisoned for political reasons in the citadel were released and the workshop, in a crowded cathedral, closed a tedeum presided by the bishop. At six o'clock and average in the afternoon the news arrived in Pamplona that the king had sworn the Constitution four days before, after affirming without conviction: "Let us march, and I the first, along the constitutional path".

The regiment of the city and the deputation, on March 16, until elections were held, were substituted by an interim board of Government that was to concentrate "the government of all the branches of the Province" -the city council of the capital and the provincial deputation-. It had been appointed by the absolutist city council of Pamplona, with the approval of Francisco Espoz y Mina, military governor of the place, in response to "the public outcry and the alarming papers that were beginning to spread". It was made up of seven people, the same issue as the absolutist deputation. It was soon criticized for having appointed "relatives and cronies" to occupy positions in the new administration.

On the other hand, a Political Chief, appointed "by uniform acclamation" of the members of the interim board of Government, replaced the viceroy; this position fell, although for a short time since he immediately left for Madrid to occupy a position in the Supreme Censorship board , in the illustrious literary Manuel José Quintana, who for his liberal ideas had been imprisoned in the Pamplona citadel. Significantly, he was the author of the Ode to the invention of the printing press, from which he proclaimed that it emerged "in triumph the truth bearing".

The constitutional province of Navarra

With the entrance in force of the Constitution, Navarre ceased to be a kingdom and became a province; consequently, the suppression of its foral regime, among other measures, brought with it new tax burdens, the obligation to serve in the army and the transfer of the internal customs to the Pyrenees, the nation's frontier. For this reason, the liberal authorities praised the generosity of the Navarrese, since they had renounced their secular privileges for the sake of national unity and the equality of all Spaniards.

After the arrival of freedom in Spain, the printing presses, subjected since their origin -350 years ago- to strict civil and ecclesiastical censorship, immediately echoed the new status and brought to light an endless number of writings: banns, proclamations, manifestos, trades, conference proceedings, powers, regulations and pamphlets, while at the same time newspapers appeared that punctually collected the activities of the government, the Cortes and the provincial authorities, without forgetting the polemics of political and religious character. This avalanche of printed matter made El Espectador de Madrid exclaim, in its first issue, which appeared on April 14, 1821:

What a lot of spitting inks! What a lot of presses since March 820! What a lot of writings, whether serious, or festive, or newspapers, or without period! What a lot of proclamations, what a lot of expositions, what a lot of manifestos! No eyes are enough, no patience is enough, no pocket is enough to absorb[sic] so much flood.

The printing presses, under the protection of article 371 of the Constitution that guaranteed the "freedom to write, print and publish", became the mouthpiece for the ideas and concerns of individuals, groups and official institutions. Immediately, in the month of March, the workshops of the capital of Navarre began to print the frequent announcements of the constitutional city council, which were pasted in strategic places of the city.

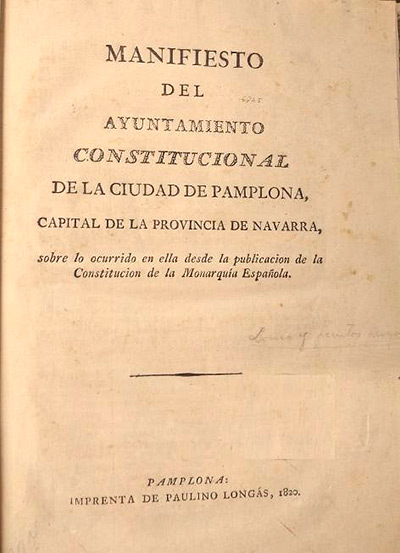

A group of military men of the Pamplona garrison, exalted liberals, published a pamphlet, printed in Zaragoza, in which they gave their version of the political events registered in the Navarrese capital since the proclamation of the Constitution. The conservative regiment of the city considered this pamphlet to be "subversive of the order" and, consequently, denounced its authors before the Censorship board of the Aragonese capital and, to refute it, published an extensive and meticulous Manifesto addressed to the public opinion in which, over 75 pages, it exposed the events that took place in the city between March and July 1820 and attached 18 official documents that corroborated them. This book detailed the process of training of the two interim governmental boards that had succeeded each other in the three-week deadline , the appointment of the mayor and the constitution of the National Militia. It was an unusual municipal initiative, aimed at informing the neighborhood.

Manifesto of the Constitutional City Council of the city of Pamplona [...]. Pamplona, Paulino Longás, 1820. Library Services de Navarra.

The protagonism of the military of Pamplona, as in other towns, was extraordinary: the following year, in 1821, 33 officers of the Toledo regiment stationed in the Navarrese capital had the pamphlet La verdad contra la mentira o relación de los acaecimientos de Pamplona printed in Javier Gadea's workshop, in which they criticized the Government of the nation and refuted some information published in El Imparcial of Madrid.

Free newspapers are born

A few weeks after the proclamation of the Constitution in Pamplona, the first newspaper in Navarre emerged from private initiative. It was El Imparcial de Navarra, which, apparently, followed the line publishing house of El Imparcial of the capital of Spain, of which the Madrid satirical newspaper El Zurriago gave a positive evaluation : "We must nevertheless warn public opinion in its favor, saying that its protectors, editors, etc., etc., are all men of good and good ideas".

The Navarre newspaper followed the format of the press of the time: it was in quarto, it occupied a sheet folded in two -which resulted in eight pages-, the text appeared in two columns and, of course, it did not have illustrations. No copies are known, so its periodicity and subscription price are unknown; it is only known that issue 5 corresponded to April 11, 1820. It is presumed that it had few means and few roots, which would explain its ephemeral trajectory, similar to so many other newspapers that emerged in this political situation in a multitude of towns. As for its orientation, the Pamplona City Council considered it akin to the interim Government board , because -in their opinion- "it inserted everything that this liberal organization wanted".

The freedom of the press favored widespread criticism, from which El Imparcial de Navarra was not spared, since shortly after its appearance, the pamphlet "Avisos que extraviados en la vali ja del graduate Imparcial de Navarra se restituuyen por la imprenta a su verdadero imparcial dueño" (Notices that were lost in the case of Imparcial de Navarra are returned by the printer to their true impartial owner), in which "counterclaims" were made to the newspaper for an information signed by the "Subscriber" that was considered to be contrary to the clergy.

![Regulations of the Patriotic Society of Pamplona [...]. Pamplona, Xavier Gadea, 1820. Library Services de Navarra. Regulations of the Patriotic Society of Pamplona [...]. Pamplona, Xavier Gadea, 1820. Library Services de Navarra.](/documents/11139712/33167456/nov2020-2.jpg/78190dd6-cd57-d3b1-26d5-fdb9deff893d?t=1621942731190)

Regulations of the Patriotic Society of Pamplona [...]. Pamplona, Xavier Gadea, 1820. Library Services de Navarra.

A few months later, at the end of 1820, the second newspaper of the capital of Navarre saw the light of day. It was entitled El Patriota del Pirineo and was edited by the Sociedad Patriótica de Pamplona, constituted on May 31 with 127 members, among whom the military predominated. It advocated an exalted liberalism as opposed to the more moderate El Imparcial de Navarra. It harshly criticized the Manifesto of the Pamplona City Council, which it perversely equated to the reviled Manifesto of the Persians that encouraged Ferdinand VII to restore absolutism in 1814.

The first article of its Regulations, a copy of which was given to each partner, defined the mission statement of the Patriotic Society: "The establishment and observance in all its parts of the Political Constitution of the Spanish Monarchy", to then proclaim that "Order, moderation and civility shall be the motto that distinguishes the Society on all occasions". Immediately, in article 3, it announced that "It shall also publish a Newspaper on the days and in the manner announced in its prospectus".

The Society had its headquarters at issue 15 San Antón Street, and here, according to the Regulations, "next to the meeting room there will be a separate room for the Members to relax, and in which the [national and foreign] newspapers or papers to which the Society subscribes will be placed, so that they can read them".

El Patriota del Pirineo, the mouthpiece of the exalted liberals, soon began to attack the moderate sector of the city, so that in issue 3, published on January 11, 1821, it denounced Ángel Sagaseta de Ilúrdoz, second mayor of the constitutional city council, who had been a trustee of the absolutist Diputación, and José León de Viguria, a member of the National Militia, for holding their posts without complying with the legal requirements .

There is news of a third newspaper, El Navarro Constitucional, of which, in spite of its masthead, Del Río assures that it was "clearly absolutist". Later, from November 1822, in the middle of the civil war, the royalists, with a printing press bought in Bayonne and installed in the fort they had built in the forest of Irati, printed, with an eloquent masthead, the newspaper La verdad contra el error y desengaño de incautos (The truth against error and disillusionment of the unwary). It was at position of the Navarrese priest Andrés Martín and the Mercedarian of the convent of Pamplona, Diego García, who were characterized, in the words of Martín himself, for maintaining "eternal hatred of the so-called constitutional system". According to Martín, 27 issues were published between November 1822 and June 1823 and distributed "throughout the towns of Navarra, and part of Aragón, and the Basque provinces". It was free of charge and its aim was to fight against "irreligion, immorality and anarchy", mission statement .

The printing press propagates political controversy

One of the first controversies in the Navarrese capital, spread by the local printing presses, was unleashed around the legitimacy of the first interim Government board . As the City Council stated in its Manifesto, "papers were immediately printed" criticizing the presence in the board of former collaborators with the Napoleonic administration and people related to absolutism.

![The Defender of the Rights of the People [...]. Pamplona, Ramón Domingo, 1820. Pamplona. Main Library de Capuchinos. The Defender of the Rights of the People [...]. Pamplona, Ramón Domingo, 1820. Pamplona. Main Library de Capuchinos.](/documents/11139712/33167456/nov2020-3.jpg/b3fcd2ef-8025-3317-883a-e4c1012c30da?t=1621942730842)

The Defender of the Rights of the People [...]. Pamplona, Ramón Domingo, 1820. Pamplona. Main Library de Capuchinos.

The first form must have been the one that bore the prolix and explicit degree scroll "The Defender of the Rights of the People and Spanish citizen. Addressed to the City Council of the City of Pamplona and board Gubernativa elected by this [city]. board established without authority / his election is a nullity, / under rules of my short science / I have to prove his insubsistence". The "Defensor", who has finished off his explicit degree scroll with a hendecasyllabic stanza, seems to be a man of law: he argues that a constitutional city council should have been formed instead of the absolutist city council proceeding, "without being the legitimate authority", to appoint an interim government board , a measure that by the way had already been adopted in other Spanish cities. He denounces, without giving their names, that at least three of the seven members of the board have "impediment of law" for the position, because two of them had been "employed by appointment of the [absolute] King" and the third for not having Spanish nationality. For these reasons he concludes that the appointment of the board is "null and void" and consequently lacks legitimacy to govern. purpose He concludes by assuring that his denunciation has the sole purpose of "attending to the preservation of good order, and to the punctual and faithful observance of what is established in the Constitution, and decrees of the Cortes".

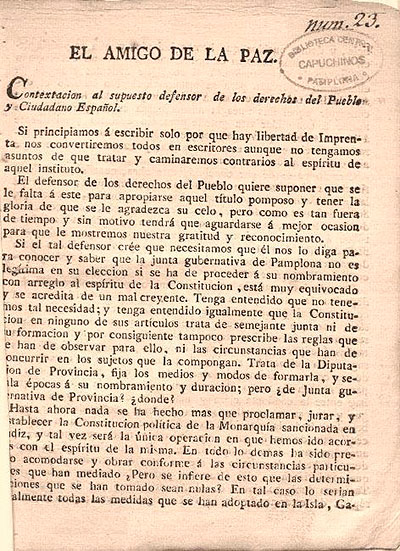

The Friend of Peace. Reply to the alleged defender of the rights of the Spanish People and Citizen. Pamplona, José Domingo, 1820. Pamplona. Main Library de Capuchinos.

The immediate response came in the pamphlet "El Amigo de la Paz. Contestación al supuesto defensor de los derechos del Pueblo y Ciudadano Español", which bears the date March 1820. The "Friend of Peace" begins by warning of the inconvenience that the misuse of freedom of the press can cause: "If we begin to write because there is freedom of the press, we will all become writers even if we do not have matters to deal with and we will walk contrary to the spirit of that high school", to then refute the thesis of the "Defender of the Rights of the People" whom he accuses of pretending "that we are governed interim by the courts, the Deputation of the Kingdom and others", which would perpetuate the absolutist authorities, instead of the interim Government board , which has been entrusted with the command during a transitional period, until the political institutions elected by the "Sovereign People" are constituted. He minimizes the objections presented by the "Defensor" to the legitimacy of some members of the board Gubernativa and, consequently, reduces them to "legal objections", while he reproaches him for choosing a "pompous" pseudonym and accuses him of being a "bad believer" to conclude by asking him: "What is it that he pretends? Is it something and more than what it seems?

![Reply to the alleged Friend of Peace by the friend of the Defender of the Rights of the People [...]. Pamplona, Ramón Domingo, 1820. Pamplona. Main Library de Capuchinos. Reply to the alleged Friend of Peace by the friend of the Defender of the Rights of the People [...]. Pamplona, Ramón Domingo, 1820. Pamplona. Main Library de Capuchinos.](/documents/11139712/33167456/nov2020-5.jpg/2446b76c-c673-a379-ec55-3bc77ec31473?t=1621942730181)

Reply to the alleged Friend of Peace by the friend of the Defender of the Rights of the People [...]. Pamplona, Ramón Domingo, 1820. Pamplona. Main Library de Capuchinos.

The reply to "El Amigo de la Paz" was not long in coming, and it appeared in the pamphlet, dated March 24, with the following address: degree scroll: "Reply to the supposed "Amigo de la Paz" by the "Amigo del Defensor de los Derechos de Pueblo y ciudadano español" (Reply to the supposed "Amigo de la Paz" by the "Amigo del Defensor de los Derechos de Pueblo y ciudadano español" (Friend of the Ombudsman and Spanish Citizen). It begins by reproaching the insults made by the "Amigo de la Paz", stating that the discussion must be carried out "without accrimination or going beyond the regular limits" and proposing a respectful tone with the contrary opinions, since the laws derived from the Constitution "grant us the School to be able to carry out our way of thinking without fear, and allow the moderate freedom of the Press, so that by its means we can express our ideas, directing them to the general and particular good of all fellow citizens". Corroborates the thesis of the "Defensor de los Derechos del Pueblo" in the sense that the appointment of the interim board of Government was improper and considers that it would have been wiser to act as in Madrid, where a town council had been constituted provisional with the members of the corporation democratically elected in 1814; in this way, the accusations of cronyism and nepotism in the designation of the board of Government of Navarre would have been avoided. He concludes by affirming that self-interested practices should end, since times have changed and "the chains that enslaved us have been broken, and when we see ourselves free, [should] we allow a dozen friends, guided by nothing more than their own interests [,] to make us the law?

![Señor Defensor de los drechos [sic] del pueblo / el Pregonero de las Tracamandainas. Pamplona, Ramón Domingo, 1820. Pamplona. Main Library de Capuchinos. Señor Defensor de los drechos [sic] del pueblo / el Pregonero de las Tracamandainas. Pamplona, Ramón Domingo, 1820. Pamplona. Main Library de Capuchinos.](/documents/11139712/33167456/nov2020-6.jpg/be8343b2-9dc0-dadc-6e6b-fdbbba0d70ed?t=1621942729843)

Señor Defensor de los drechos [sic] del pueblo / el Pregonero de las Tracamandainas. Pamplona, Ramón Domingo, 1820. Pamplona. Main Library de Capuchinos.

"The Defender of the Rights of the People" receives a new attack, this time by "The Pregonero de las Tracamandainas [algarabías]". He agrees with him that some members of the board of Government are not legitimized to perform their position and boasts that he knows much more about their incompatibilities and machinations, although he keeps quiet about them to avoid "the wrath of the people". On this occasion, the tone of the polemic rises, because in spite of beginning his plea respectfully addressing "Mr. Defender of the Rights of the People", he immediately goes on to call him a "fool", a "shirker who keeps silent only about what he ignores" and of belonging to those who only know how to "suck and take advantage of everything". He considers that with the freedom of the press "now we can all write" with or without foundation, as he assures that "El Defensor" has acted. He also criticizes "El Amigo de la Paz" for proposing "with twisted arguments" to ignore the "tachas" presented by some of the members of the interim Government board .

It is possible to think that this political confrontation had a wide echo in Navarre due to the importance of the issue -the legitimacy of the government provisional of the province-, the social relevance of the denounced characters and, evidently, its diffusion through printed matter, economic for its promoters and of massive distribution, which undoubtedly constituted a novel means of communication.

Be that as it may, the board Government, after resigning three times, was dissolved on March 23 because it understood that "it inspires the people with distrust in its determinations, and its establishment is attacked for lack of legitimacy". It had lasted one week. The one that succeeded it, constituted on April 8, was made up of two military men and a representative for each of the five merindades, all of them presided over as "protector" by Francisco Espoz y Mina, "Captain General of the Province of Navarre". Both this and the previous one were under the tutelage of this military man from Navarre and maintained a radical position within the prevailing liberalism.

The printed matter that aired this and other similar controversies was generally presented in the form of a four-page pamphlet, headed by a degree scroll highlighted in a tall box or with ornamented type, and justified in the center; the text was in one line, printed in one ink, with adequate margins and tended to occupy all the pages; subject vignettes or any other typographic ornamentation were not included, except for a simple initial capitular or a fillet under the degree scroll; the lettering was round, with some italics to underline certain expressions and at the end the name of the printer, the address of his workshop and the date were usually included, while the author was masked behind a pseudonym that appeared inside the degree scroll or at the end of the writing. They must have been urgent orders, which required a low economic cost since their distribution would be free of charge.

Adventure and misfortune of printers

From what has been explained so far, it has been possible to verify the boom experienced by the printing press in the light of the emergence of freedom guaranteed by entrance in the spring of 1820, of the Constitution of Cadiz.

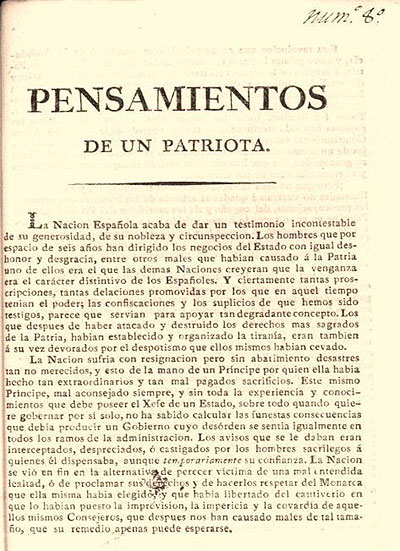

Joaquín Domingo, Thoughts of a patriot. Pamplona, Joaquín Domingo, 1820. Library Services de la Colegiata de Roncesvalles.

The printers received an avalanche of orders, fundamentally small jobs in which immediacy predominated over typographic quality, but which probably provided them with a moment of economic boom and turned a good part of them into champions of freedom. This is the case of Joaquín María Domingo, from a family of typographers, who in the early stages of the Liberal Triennium publicly proclaimed his support for the Constitution in a neatly printed four-page pamphlet graduate "Pensamientos de un patriota", which signature with his name and surname, while others preferred to hide behind a pseudonym. He ponders the peaceful nature of the revolution that has brought freedom to Spain and like many others does not trust the sincerity of the oath to the Constitution taken by Ferdinand VII, warning him -with the text underlined in italics- that if he does not comply with it, "the stability of the Throne, the rights of the reigning family and therefore public tranquility" are in danger. He also calls for the Cortes to meet as soon as possible in order to consolidate democracy and demands that the pulpits do not take sides with the reaction. In a clairvoyant manner, he warns about the threat of "foreign aid" and sings of the recently inaugurated freedom of the press in order to confront the lurks of the reactionaries:

Freedom of the press, which the agents of tyranny have so viciously persecuted, is one of the rights that the Nation has come into possession of. By this means, all their machinations and treacherous efforts will be made public and will be denounced so that all the attempts with which they will try to enslave us again will be punished.

Joaquín María Domingo ends his reflection by exalting the military who have returned sovereignty to the people with the cry of "Liberty and peace!", warning them, again in a premonitory manner, that if they fail in their endeavor they will suffer the same fate that the authors of the Constitution of Cadiz suffered in 1814: repression and exile.

The liberal enthusiasm of this Pamplona printer was short-lived, because the restoration of absolutism at the end of 1823 meant the repression of the liberals: the most influential were able to flee abroad, but the modest ones, like him, appeared on the list of outlaws and paid the consequences. He had shown his liberal enthusiasm in "Pensamientos de un patriota", he had printed the newspaper of the Sociedad Patriótica de Pamplona and in his works he had declared himself a "citizen"; for all these reasons, his printing press was definitively closed when he was 44 years old.

His brother José Fermín, who had printed in his workshop the pamphlet signed by the "Friend of Peace" and who had participated in the National Militia formed in April 1820, was also repressed and his workshop Closed forever.

The third Domingo brother, Ramón, with a worrying background -he had worked for the Napoleonic troops-, showed his support for the Constitution. Like his brother José Fermín, he joined the National Militia and, among other works, printed in his own workshop the pamphlets "El Amigo del Defensor de los derechos del pueblo" and "El Pregonero de las Tracamandainas". His printing press was closed in 1823 and remained closed for ten years, until the death of Fernando VII.

The veteran printer Paulino Longás, who had been sanctioned in 1816 for selling banned books, in 1820 printed the Manifiesto del Ayuntamiento ( Manifesto of the City Council), which was mentioned at accredited specialization and, on the other hand, he made profits by selling official publications, such as the regulations of the National Militia, which he printed and sold, since the board of the Government of Navarra lacked the money to do so, as he confessed to the City Council of Pamplona at official document on April 20, 1820:

As this board does not have funds with which to pay for the printed copies of the National Militia Regulations provisional , all those towns that want to buy them can go to the Longás printing house in this city.

He gave testimony of his liberal militancy by joining the National Militia as a volunteer. He was repressed, although the printing press continued to work despite the fact that in 1826 he was imprisoned for the sale, once again, of banned books.

Javier Gadea, who in 1820 had printed the Regulations of the Patriotic Society of Pamplona, was safe from the repression unleashed after the restoration of absolutism and his workshop worked smoothly attending, to a large extent, orders from clergymen and convents.

The printing house run by Micaela Sengáiz, widow of José Francisco de Rada, although it had also printed liberal publications, continued its activity throughout the century without problems, although it should be noted that from 1824 onwards it was run by Francisco Erasun y Rada, possibly due to the death of his aunt, Micaela Sengáiz. From then on, the new owner received frequent commissions from the civil and ecclesiastical authorities.

For the ephemeral enjoyment of freedom during the Liberal Triennium, its supporters, harassed by the Purification Boards established in all the provinces, had to pay a high price throughout the Ominous Decade. In the case of the six printers in Pamplona, the only ones in Navarra, four were retaliated against and three of their workshops were closed.

Fleeting freedom

Freedom of the press in the province of Navarre was more ephemeral than in other territories; it broke out in March 1820, but from the beginning of the following year it began to decline, weakened by the constant urban altercations, based on bayonetings and stones, between the troops and the absolutists, among whom the seminarians played a special role. The status worsened from spring onwards with the appearance of the first actions in open fields by "factious parties" and "gangs of bandits" - as the liberal press described them - who threatened the constitutional authorities and in the towns requisitioned horses, arms and food.

In 1822, in the bloody workshop of Pamplona on March 19, commemorating the tenth anniversary of the Constitution, in the course of three hours of shooting five soldiers and two civilians were killed and 29 wounded. In mid-June, the board Realista called for an uprising through a massively distributed leaflet addressed to the "brave and generous Navarrese", which ended with "Long live the Religion, the King, the Homeland and die the Constitution!", which soon led to armed conflict -the state of war was proclaimed in Navarre on August 11-.

The status of the liberals became critical when in March 1823 the royalists laid siege to Pamplona, where the supporters of the Constitution, now more reluctant than in 1820 to proclaim their ideals, took refuge. The siege ended six months later, when Pamplona loyal to the Constitution of 1812 surrendered to the troops of the Holy Alliance, recruited by the authoritarian monarchies of Europe, who had invaded Spain to "put an end to the anarchy that desolates [sic] Spain" -as they proclaimed shortly before crossing the border- and restore Ferdinand VII to the throne as absolute king. Once the constitutional regime was overthrown, the repression of those who had supported it was unleashed. The price paid by most of Pamplona's printers for this was already known.

SOURCES AND BIBLIOGRAPHY

AGN (file General de Navarra). Processes 63489. 1882. Complaint against "El Patriota del Pirineo".

AGN. Proceedings 194542. 1810. Workshop of Joaquín Domingo.

AMIGO de la Paz, El: Contestación al supuesto Defensor de los Derechos del Pueblo [...]. Pamplona, José Domingo, 1820. Main Library de Capuchinos. available en Binadi. (Accessed 21-IX-2020)

CONTESTACIÓN al supuesto Amigo de la Paz por el amigo del Defensor de los Derechos del Pueblo [...]. Pamplona, Ramón Domingo, 1820. Pamplona. Main Library de Capuchinos. available in Binadi. (Accessed on 21-IX-2020)

DEFENSOR de los Derechos del Pueblo y ciudadano español, addressed to the City Council of the city of Pamplona, El [...]. Pamplona, Ramón Domingo, 1820, pp. 1-4. Pamplona. Main Library de Capuchinos. available in Binadi. (Accessed on 21-IX-2020)

DOMINGO, J. Pensamientos de un patriota. Pamplona, Joaquín Domingo, 1820. Library of the Collegiate Church of Roncesvalles. available in Binadi. (Accessed on 21-IX-2020)

HERRERO MATÉ, G. Liberalism and National Militia in Pamplona during the 19th century. Pamplona, Public University of Navarra, 2003.

ITÚRBIDE DÍAZ, J. J. Los libros de un Reino: Historia de la edición en navarra (1490-1841). Pamplona, Government of Navarre, 2015.

MARTÍN, A. Historia de la guerra de la División Real de Navarra contra el intruso sistema llamado constitucional y su gobierno revolucionario. Pamplona, Imprenta de Javier Gadea, 1825. available in Binadi. (Accessed 24-IX-2020).

PAMPLONA, City Hall, The constitutional City Council of this city that [...] wishes [...] to instruct this [...] neighborhood of the steps it has taken as a result of the unfortunate scenes of 19 of the current [...]. [Pamplona, City Hall, 1822]. Library of Navarre. available in Binadi. (Accessed on 21-IX-2020).

PAMPLONA, Ayuntamiento, Manifiesto del Ayuntamiento constitucional de la ciudad de Pamplona [...] sobre lo ocurrido en ella desde la publicación de la Constitución de la Monarquía Española. Pamplona, Paulino Longás, 1820. Library of Navarre available in Binadi. (Accessed on 21-IX-2020)

RÍO ALDAZ, R. del, Origins of the Carlist War in Navarre (1820-1824). Pamplona, Government of Navarre, 1987.

SEÑOR Defensor de los drechos [sic] del pueblo / El Pregonero de las Tracamandainas. Pamplona, Ramón Domingo, 1820, pp. 5-8. Pamplona. Main Library de Capuchinos. available in Binadi. (Accessed on 21-IX-2020)

SOCIEDAD PATRIOTICA (Pamplona), Reglamento de la Sociedad Patriótica de Pamplona, printed by disposition of the same. Pamplona, Xavier Gadea, 1820. Library of Navarre. available in Binadi. (Accessed 21-IX-2020).