The piece of the month of September 2020

WORK IN THE VINEYARDS IN THE MEDIEVAL CALENDARS OF NAVARRE

Carmen Jusué Simonena

UNED Pamplona

The months of September and October are harvest time. This ancestral wine festival has been celebrating for centuries the fertility of a land protected by gods and adored by mortals; a fascinating union between the divine and the earthly, with those everlasting but ephemeral fruits sprouting each new cycle, in the words of L. López Altares. With the end of summer comes one of the most important moments involved in the elaboration of the new wine. It is the grape harvest, the moment of the wine.

To approach the meaning of the grape harvest throughout history is to enter into that magical moment when gods and men intermingle, when the earth reveals itself in all its grandeur and generosity, showing its exuberant fruit. It is not surprising that the great civilizations looked to the sky while caressing the earth in search of a divinity to explain an event as sacred as it was profane; in ancient Egypt to the god Osiris, to whom the origin of wine was attributed, and in ancient Greece to Dionysus, who symbolized youth and eternal life and in his festivities the people gave themselves to rejoicing and debauchery for days through songs, dances or passions.

Exquisite representation of the grape harvest in the capitals of the façade

of Santa María de Ujué. Photo: C. Martínez Álava.

The Romans inherited from Greece the love of wine and, like the Greeks, they worshipped Bacchus or Liber, initially god of vegetation and, when the vine became important, protector of vine growers, who was worshipped on March 17 in the Liberalia. Other festivals that included Bacchus or Liber, although dedicated to Jupiter and Venus, were the Vinalia, in which protection was requested for the vineyards and the grape harvest and the first must of the harvest was offered.

There is no spring without flowers, nor summer without heat, nor autumn without bunches, nor winter without snow and cold, a saying that accurately summarizes the seasons of the year, but it is not the seasons that will be the subject of these lines but rather the medieval representations of the months of the year in which the work in the vineyards takes place, which with their different images illustrated the calendars or calendars that were developed in Spain in the Romanesque period and did so, in the words of Professor R. Fernández Gracia, with the vision of work imposed by God. In addition, those tasks spoke graphically of the passage of time in the human evolution, and really constituted a didactic resource .

Calendars - Mensarios in Navarra

In Navarre, the mensarios have several versions from the Gothic period, at a time when they did not appear in doorways and large spaces, but rather they came to occupy other places such as keystones, painting in arches or spaces in altar fronts, as has been shown in his study for Spain by Professor M. A. Castiñeiras, who considers that due to their privileged geographical location and their political and dynastic relations with France, Navarre and Aragon introduced the new modes of French Gothic linear painting, although without altering the French Gothic style. A. Castiñeiras, who considers that due to their privileged geographic status and their political and dynastic relations with France, Navarre and Aragon introduced the new modes of French Linear Gothic painting, although without altering the content of the Hispanic calendars.

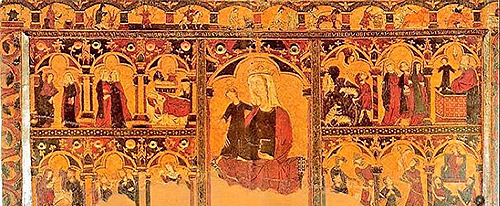

These calendars, which seem to obey a positive and edifying vision of work, are found in Navarre in the Eguíllor altar frontal, which belonged to the collector Riccardo Gualino, who in 1928 donated it to the Italian state and is currently in the Gualino section of the Galleria Sabauda in Turin. They also appear on the Góngora and Arteta frontispieces that belonged to the old Plandiura collection and, since 1908, have been in the Museum of Art of Catalonia. In the three frontispieces, the representations of the mensario are located in the upper part, being the one by the master of Arteta the one that best preserves the cycle and the one with the highest quality, since it unites in a successful synthesis the Romanesque-Pyrenean painting, the style derived from the Parisian Gothic and the iconography of the Hispanic calendars, according to M. Castiñeiras.

Arteta frontal and its details. The representations of the months are located in the upper part of the frontal.

A third calendar appears -except for the month of June- in the keystones of the cloister of the cathedral of Pamplona, with themes from the Romanesque repertoire Spanish, eight of them in the northern gallery and the rest in the west gallery; this strange arrangement is due, according to Professor C. Fernández Ladreda, to the fact that perhaps the complete cycle was projected in one gallery and later this plan was altered.

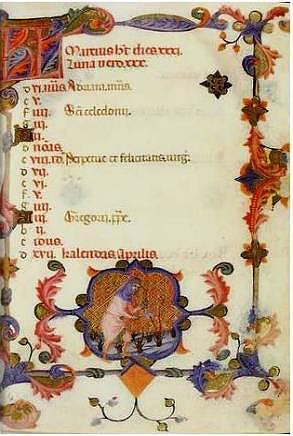

A fourth example, with mural paintings, appears in a sash arch of the parish church of San Martín de Ardanaz de Izagaondoa, which have been studied by C. Martínez Álava and dated by M. Zuza between 1354 and 1361. Finally, thanks to the taste of the court and the minor nobility for secular themes, calendars began to appear in the decoration of objects of use staff, being illustrative the very beautiful Book of Hours of Queen Mary of Navarreillustrated by Ferrer Bassa, among other artists, and which has, among other miniatures, a calendar to which zodiac signs are added.

Pruning, barrel preparation, grape harvesting and crushing of grapes

After the cold winter, March brings the first warm temperatures that favor the beginning of work in the fields. Naked and dry, the shoots need a careful work to avoid a lousy harvest. It is time to repair and straighten the vines and start pruning work so that the fruit can be harvested at the end of the summer. All the Navarrese calendars, except the Ardanaz calendar in which the scene has not been preserved, depict a farmer holding a vine shoot with one hand and cutting with a large pruning shear with the other. Unlike other peninsular calendars, the characters of the Navarrese, in the face of the harshness of the cold, appear wrapped up and wearing a hood or hat, except in the Book of Hours in which, although hooded, he wears a light tunic.

|

|

|

Representations of the month of March in a core topic of the cathedral of Pamplona,

in the Book of Hours of Mary of Navarre and in the calendar of Ardanaz, of which only the name of the month is

of which only the name of the month is preserved.

The time has come to separate the wheat from the chaff. August is the month of threshing, represented in the cloister of Pamplona by the figure of a peasant who, seated on a threshing floor and leaning on a stick, leads a pair of mares, a scene very similar to that of Ardanaz and the frontals of Arteta, Góngora and Eguíllor in which the artist wanted to emphasize the heat by presenting the peasants with short tunics or skirts. However, in the Book of Hours the month of August is represented with two peasants preparing a vat, a task that had to be done just before the beginning of the grape harvest.

Representation of the month of August, with the preparation of barrels,

in the Book of Hours of María de Navarra.

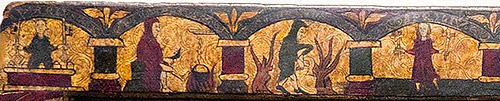

In the Roman calendars the month of September is prescribed for the tarring of the jars and in the Age average the moments prior to the grape harvest were used to adjust the straps of vats and barrels. It is also the month when the grape harvest begins and the grapes are trodden. In the Navarrese calendars, with the exception of the Book of Hours in which the month of September is represented by the grape harvest, the work carried out is limited exclusively to the preparation of the vats or the transfer of the wine. In Ardanaz there are two characters: one of them stands behind the barrel and the one in the foreground holds a hammer with which he prepares to adjust the straps, a task identical to the one observed in the other fronts in which a single person holds the edge of the vat with one hand and with the other one fixes the straps with a hammer.

|

|

|

Representations of the month of September in a core topic of the cathedral of Pamplona,

in the calendar of Ardanaz and in the Book of Hours of María de Navarra.

Different is the one represented in the cathedral of Pamplona, a beautiful image that for several years was the logo of the committee Regulator of the wine of Navarra. The scene corresponds to the transfer or racking of the wine that was carried out with the financial aid of a skin wineskin and a funnel, and consisted of filling the half-empty vats with wine after fermentation, a task that was generally carried out inside the cellars that were part of the house, monastery or palace. The core topic presents a character of profile and looks straight ahead, bending his back under the weight of the wineskin and pouring the wine into the vat.

Tillage, the time of the agricultural year when the land is plowed and sown, is the one that appears in the month of October. While in the Book of Hours the representation of this month is again related to the vine, given that sample the treading of grapes and the extraction of the must, the other Navarrese calendars present the work of preparing the land and sowing.

Representation of the month of October, with the treading of the grapes,

in the Book of Hours of María de Navarra.

This relation or description of months is not exclusive to pictorial or sculptural art, since there are extraordinary literary examples of the same motif. Thus, to cite one example, the Book of Alexandre, a work in verse from the first third of the thirteenth century that narrates with abundant fabulous elements the life of Alexander the Great, there is a very curious part in which the months of the year are described as if they were represented precisely in the king's tent, although in reality what is described is the decoration of a medieval temple or a tapestry of that time, possibly the Romanesque tapestry of the Creation, from the 11th century -a unique and exceptional piece among the few embroideries known and preserved in the cathedral of Gerona-, in which the representations of the months are arranged in a special way. The tapestry measures 3.58 x .50 meters. Regarding the months of March, September and October, it says:

2.521. March avie un grant priesa de sus viñas labrar,

priesa with pruners and priesa with digging,

fazie aves et bestias ya en çelo andar,

the days and nights fazielas equal.

2.527. Setienbre traye varas et sagudie las nogueras,

apretava las cubas, prunava las minbreras,

harvesting the vines with pruning shears,

non dexava los paxaros llegar a las figueras.

2.528. Estava don octubre sus missiegos faziendo,

rehearsing the wines that yazién already firviendo,

iva as again his things requiring,

iva to sow, the winter coming.

Likewise, the Archpriest of Hita, in the 14th century Book of Good Love , introduces the peasant calendar when speaking of the tent in which Amor is installed, and at purpose of the months in which grape harvesting is carried out, he relates:

"Three farmers come all at once degree program

The first [August] already ate the ripe grapes.

The second one [September] plows and presses the vines

He begins to harvest grapes from the vines

The third [October] farmer treads on the good wines

Finches all his vats like a good winemaker".

SOURCES AND BIBLIOGRAPHY

CARO BAROJA, J., "Representations and names of months. A purpose del menologio de la Catedral de Pamplona", Príncipe de Viana, VII, no. 25, 1946, pp. 629-653 + 21 plates. Enlarged at issue 56.

CASTIÑEIRAS GÓNZALEZ, M. A., El calendario medieval hispano. Textos e imágenes (siglos XI-XIV), Salamanca, board de Castilla y León. Consejería de Education y Cultura, 1996.

JUSUÉ SIMONENA, C., "En torno al vino y las uvas. IV. Bien valdra como creo, un vaso de bon vino. Field work in medieval calendars", Diario de Navarra, August 1, 2020.

MARTÍN, J. L., Vino y cultura en la Edad average, Zamora, UNED, 2002.

PÉREZ SUESCUN, F. and RODRÍGUEZ LÓPEZ, M.ª V., "Aportaciones al estudio de los calendarios medievales navarros", Tercer congress General de Historia de Navarra. area II, Artistic currents, Pamplona, 1994, pp. 2-16.