The piece of the month of April 2021

CHALCOGRAPHIC ENGRAVING OF THE VIRGEN DE LA CERCA DE ANDOSILLA (OUR LADY OF THE FENCE OF ANDOSILLA)

Ricardo Fernández Gracia

Chair of Navarrese Heritage and Art

University of Navarra

After the publication of our monograph on devotional prints in Navarra (Madrid, Fundación Ramón Areces, 2017), we were always aware that, in some collections, or in trade and auctions, new specimens would appear to add to the intaglio prints studied and catalogued. The foresight failed us, as so far we have had almost no knowledge of others and we have barely been able to add the one we present here. It is a copy printed on yellow taffeta, dedicated to the Virgen de la Cerca de Andosilla, which has been kindly made available by José María Muruzábal, whom we thank for his kindness.

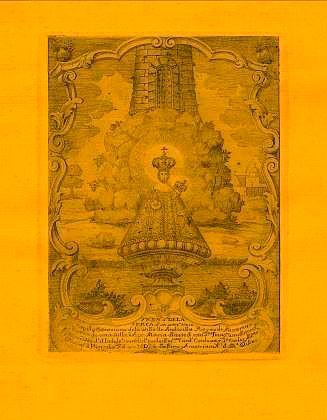

The composition is framed in a mixtilinear border of typically rococo braces, with an area for the registration at the bottom and a pair of plumb vases, with the ends of the pediment as a finial. The image is in front of a rocky area, topped by a tower of large ashlars. On both sides, a tree and a temple, which alludes to the Shrine of Our Lady of Fair Love of the Virgin. The Virgin sits on a large pedestal, wears a mantle and apron and has a rich rostrum and a graceful crown. In the lower part, some bushes and plants speak of the place of the apparition.

The iconographic interpretation of the Marian icon, which is located in front of an enormous tower of a walled complex, takes us directly to the legend of Our Lady of the Fence that Rufino Oyón collected in his Historical Compendium and Novena of the Virgin of the Fence, published in 1886. According to this author, in a parchment document kept by Don Domingo Moreno, in the second half of the 16th century, a certain José María Amatriain hid the image in the 8th century, which would later be found in the 13th century. Both events would have taken place next to the defensive complex of the castle keep and its fence.

The image was venerated and in its old sanctuary several votive offerings could be contemplated, today missing or untraceable. The old Shrine of Our Lady of Fair Love was practically rebuilt in 1951. In 1995 a completely new one was inaugurated in a new, more central location. The old one was located at the end of the Arrabal, at the foot of a high tower, built, according to the legend, under the Muslim domination.

It is noteworthy that the engraving was paid for by a member of the Amatriain family, as we shall see, and that one of the votive offerings in the sanctuary also featured a girl from the same family clan. The painting of the ex-voto had the following registration: "The girl Lorenza Romana Laparra y Amatriain, being seriously ill, her pious parents entrusted her to the Virgin of the Fence, and she obtained a complete and sudden health, with great admiration of the doctors, year 1772". The tradition and these two facts link in a clear way the special relationship of the image with those who carried that surname of Amatriain.

The copy of the engraving studied does not bear any date, but its style with tornapuntas and rocailles places us in the decade of 1760, something that can also be deduced from those who appear in the content of the registration that reads as follows: "Vº Rº de Nª Sª DE LA / CERCA, q. se venª en su / Capilla extramuros de la Villa de Andosilla Reyno de Navarra / Rezando una Salbe o Ave María delante d esta Stª Imagn o sus Estamps / se ganan 280 ds de Indulgs condedids por los Emmos Cards Cordova y Sn Carlos y Illmo / Arzobpº de Pharsalia A devocn de D. Jph dela Parra y Amatriain nl dhª Villa".

Engraving of the Virgen de la Cerca de Andosilla.

The promoter of the printing plate, Don José de Laparra y Amatriain, was born in Andosilla, in whose parish he was baptized on October 11, 1719 (Libro IV de Bautizados 1700-1743, fol. 52v.). His parents were José de Laparra y Navarro and Josefa Amatriain Teres, who had married on March 3, 1710 (Libro de Casados 1685-1767, fol. 39). It is very possible that his life was spent outside of his native town, since his trace is lost in the sacramental books.

Cardinal Cordoba should be identified with Don Luis Fernandez de Cordoba, promoted to the cardinal dignity in December 1754, without degree scroll, and in August 1755 he was appointed archbishop of the primate see of Toledo. He died in March 1771. The archbishop of Farsalia at that time in the third quarter of the 18th century could have been Don Manuel Quintano de Bonifaz, inquisitor general, who was with that degree scroll since 1749 and died in 1774. With the degree scroll of Cardinal San Carlos we do not know to which cardinal it can refer. With all certainty, the requests for those indulgences, as in other cases, would have been requested by the patron of the print, Don José de Laparra y Amatriain.

In addition to the devotion of the aforementioned promoter, it should be noted that the cult of the aforementioned image experienced an enormous growth in those decades of the eighteenth century. Thus, in 1759 a novena was made, transferring the image to the parish, in 1767 another novena was made, in 1775 another two, and in 1785 and 1786 others. In 1796 and 1798 those functions were repeated, which were almost always motivated by droughts. Even a devotee residing in Valladolid de Michoacán, Don Francisco Ximeno, when he died, gave six silver candlesticks for the Virgen de la Cerca, in 1796 (Libro de Difuntos desde 1790, fol. 41v.).

Like other prints of this subject, Professor Carrete Parrondo rightly wrote in the prologue to the aforementioned monograph:

It is well known that from the 15th to the 19th century, prints have been the most important means of disseminating both images and ideas. Their multiple character is their most genuine characteristic, there is no single copy, what is sought is the existence of many identical reproductions from an engraved copper plate. If we apply this characteristic to religious prints, the so-called devotional prints, we will realize the important role they played in the training of the mentalities of the time and, therefore, how fundamental their knowledge is for the history of both thought and art.

As for the promoter, one can guess a special fondness, possibly from outside the homeland, for the fact of emphasizing in the registration that he was a native of the town of Andosilla. He was neither the first nor the last. The purpose, obviously, was to collaborate with the diffusion of the cult to the image, something that in that context was in agreement with the data that we have contributed. The promotion of devotion was, without a doubt, its primary purpose. All those images were destined -like the canvases of Virgin advocations, as "trompe l'oeil to the divine", or as hagiographies on paper- to the simple people, in whom they inspired the same respect and piety as the altarpieces, sculptures and paintings of the temples, at the same time that for a modest price they could have their favorite images to satisfy their particular devotions. In this way, the interest of confraternities and devotees to possess the "true portraits" and the "miraculous images" as they were venerated in the churches was fully compensated by acquiring in the sacristies, convents, sanctuaries, festive fairs, booksellers, stamp dealers or peddlers, the prints of their devotion.

Those images on paper constituted the best example of mass and popular communication in past centuries, with a presence in the life of our ancestors across the social spectrum, as objects of contemplation in everyday life. It should be remembered that they were found in humble homes, stuck to the wall with wafers of bread or rustic boards, and also in mansions and palaces of good standing. In the latter cases they were richly framed and decorated with sequins, golden lace and other ornaments, seeking luxury and wealth along with those poor objects themselves.

These engravings, together with medals, measures, scapulars and gozos, are part of a set of pieces that people required to see and touch something related to the spiritual dimension of the set of abstract and immaterial principles that regulate the relationship between man and divinity. These objects allowed a more intense and intimate connection between the aforementioned binomial, at the same time that they constituted genuine witnesses of the daily religious internship of different generations of the faithful, of their feelings and devotions.

Intaglio as model of an 1881 lithograph.

As happened with other prints opened to burin in the 18th century, such as the Virgen del Yugo de Arguedas, the eighteenth-century model was used for the realization of lithographs throughout the second half of the 19th century. The engraving of the Virgen de la Cerca was copied in lithographs of two sizes in 1881, at the expense of the chaplain of the sanctuary, Mr. Adrián de Goicoechea. The lithographer who did that work was Sixto Díaz de Espada, born in 1826 and died in 1913. He ran his printing, bookshop and lithography establishment on San Nicolás Street and Paseo de Valencia in Pamplona and produced several editions between 1859 and 1891.

Lithograph of the Virgin of the Fence of Andosilla.

SOURCES AND BIBLIOGRAPHY

file Diocese of Pamplona. Parish Books of Andosilla.

Diario de Navarra, March 14, 1913, p. 1. Data from Catalog Collective of the Bibliographic Heritage of Navarre, for which we thank Roberto San Martín.

FERNÁNDEZ GRACIA, R., Imagen y mentalidad. Los siglos del Barroco y la estampa devocional en Navarra, Madrid, Fundación Ramón Areces, 2017.

FERNÁNDEZ GRACIA, R., Versos e imágenes. Gozos en Navarra y en una colección de Cascante, Pamplona, Universidad de Navarra-Fundación Fuentes Dutor-Vicus, 2019.

GÓMEZ ALONSO, F., "Imprentas e impresores durante los siglos XVII-XX", La imprenta en Navarra, Diputación Foral de Navarra-Institución Príncipe de Viana, 1974, pp. 232-233.

OYÓN, R., Compendio histórico y novena de la Virgen de la Cerca, 1886.

PÉREZ SÁNCHEZ, A. E., "Trampantojos a lo divino", Lecturas de Historia del Arte. Ephialte (1992), pp. 139-155.

PORTÚS, J. and VEGA, J., La estampa religiosa en la España del Antiguo Régimen, Madrid, Fundación Universitaria Española, 1998.