The piece of the month of August 2021

NEW IMAGES OF THE HAND OF FRIAR JOHN DE BEAUVES AT ELCANO

Pedro Luis Echeverría Goñi

University of the Basque Country

One of the paradoxes of pre-Renaissance altarpieces in Navarre is the absolute documentary prominence of the carvers and architrave makers, leaving in the background or silenced in the writings, on the contrary, the work of the best image makers who worked under them, as in the case of Arnao Spierinck of Brussels. Friar Juan de Beauves, an exquisite master of early Mannerism, does not escape this dichotomy, although in this case we have three brief, though conclusive, acknowledgements of his skill and authority, which include as a guarantee that the images and stories of average carving would be executed "by the hand of Peti Joan, the friar" (tracing of the main altarpiece of Esquiroz in 1575), who would also supervise the entire execution process. This praise of the sculptor from Navarre of Picardy origin places him in the wake of the great 16th century artists such as Michelangelo and Raphael Sanzio, whose patrons requested in the contracts for some of the Madonnas, altarpieces and faces that they be executed "per la mano di maestro Rafaello" and not by the officials of his workshop.

However, a fundamental part of his dense production in Navarre and Alava remains anonymous due not only to his wandering life, his almost non-existent documentary presence or the loss of the account books and deeds, but also to other causes such as the transfer of the carvings, their inclusion in later Structures and, above all, the successive repolychromies and repainting that have disfigured them. We know that he placed his gouge at the disposal of various archivists and carvers from Villanueva de Araquil - such as Juan de Landa Mayor, Juan de Elordi, Miguel Marsal and Beltrán de Andueza -, Alsasua - such as Juan de Madariaga -, Villava - such as Nicolás Pérez - and Pamplona - such as Pedro de Moret and Antón de Huarte. partnership A separate chapter was his close relationship with the carver Pierres Picart (Duran), a native of Péronne (Perona) and resident of Oñate, which continued with his son-in-law Lope de Larrea y Ercilla, a sculptor from Salvatierra (Álava), with whom we know he formed a company. He is the creator of the characteristic types of Raphaelesque Madonnas and expressive Crucified Christs.

Although Juan de Beauves' prolific period took place in the second half of the 16th century, his unmistakable style always remained faithful to expressivism, despite the fact that he met Juan de Anchieta and Lope de Larrea and, with them, the spread of Romanism. His classicist and elegant works are a three-dimensional transposition of Raphaelesque and Michelangelo models known from engravings. His years at training in Saragossa between 1533 and 1537 with Gabriel Joly mark the beginning of his Florentine classicism, from which he progressed to a Raphaelesque mannerism of his own from the late fifties of the 16th century. His longevity allowed him to evolve, as did his reference Raphael, from the Florentine Madonnas to the Roman Madonnas, as he became acquainted with the work of Michelangelo.

In the rich trousseau of the parish church of Elcano we recognise the unmistakable gouge of Friar Juan de Beauves in the carving of two of its altarpieces of painted panels, the main scene of the main altarpiece, which can be dated to the 1960s, and the lump of Saint Michael and the Crucifixion of the collateral altarpiece of the Gospel, executed a decade later. Thus, in the "full relief" of the Purification of Mary and presentation of Jesus in the Temple, we can see how the Virgin corresponds to those beautiful feminine types of our artist, with an oval, broad face, large eyes and, in contrast, a small, pinion-like mouth, as well as wavy curls and delicate hands with long fingers. This model also applies to the Child and saints, youths, children and angels, who used to receive clear incarnations based on white lead and vermilion, with their hair covered in matt gold. It also characterises men with wide faces and very pronounced cheekbones, some of them with a tuft of hair falling on their foreheads. As befits their sex, they were given dull, dark incarnations, as in the case of Saint Joseph, which darkened with earth and ochre according to their age, as in the elderly Simeon and Anna. Their figures repeat classical counter-posts and show an elongated canon that adheres to the five-fold proportion. They are dressed in overlapping garments, close-fitting and with elaborate pleats, which are decorated with fine, original, fantastical Mannerist estofados.

The extraordinary compositional coincidence between this relief and the Circumcision of the main altarpiece in Lumbier (1563), a documented work by the artist, confirms the attribution of this relief to the Friar. Although they are different episodes, both show Simeon and Mary in identical location, iconography and attitude. The Child, with a similar foreshortening, is in Lumbier in the arms of the Virgin, ready to be cut, while in Elcano he is held by the just man who has become a priest. The only change is the figure of Saint Joseph, who in Lumbier is located in the centre as the axis of symmetry and in Elcano is in the background behind Mary, next to the prophetess Anne. The most noticeable changes affect the elements of the setting in the church, such as the altar table (square in the first case and set at an angle, and round in the second) and the drapery (gathered at both ends, with winged cherub heads in Lumbier, and with a canopy over the Christ Child held by Simeon).

Photomontage of the Purification-presentation of the main altarpiece of Elcano. framework architectural and inscriptions. Lower left-hand side, Lumbier. Circumcision of the main altarpiece (Artres).

This scene emphasises the presentation of Jesus and, more specifically, the manifestation or meeting with Simeon, who raises the Child in the presence of his parents and the prophetess Anna, while exclaiming "Nunc dimitis", an expression of the joy of messianism. The Purification of Mary is celebrated simultaneously with the offering of the two young pigeons that Joseph places on the altar in a small basket, although the characteristic candles are omitted, the only concession to light being the two genuflecting lighting angels who, sheltered in niches, flank this story. The box that houses the titular high relief and its frame form a specific Mannerist micro-architecture within the layout of an altarpiece in a box, as it covers the two sections of the box and protrudes from the plan. It consists of a bench with a cartouche between St. Peter and St. Paul and a stage section, flanked by truncated Corinthian columns on telamons. On the presentation the story continues with reliefs, in the form of vignettes, of the Magi before Pilate, the Slaughter of the Innocents and the Flight into Egypt.

It is a didactic composition, as the figures are arranged in the foreground in front of the faithful, without any concession to the architectural background or distracting anecdotal details. We can distinguish two groups carved in high relief in two independent pieces that establish a spiritual hierarchy in this story. To the left of the viewer is the elderly Simeon holding the Christ Child in his arms on a cloth of respectful calligraphic folds, blessing him as the promised Messiah and at the moment of returning him to his mother. He is dressed as a High Priest with a surcoat and a mitre with horns in the oriental manner. His moralised background is a canopied curtain with a canopy that, together with the altar, forms the only reference letter to the temple and serves to sacralise the divine figure. The circular altar table with a white tablecloth serves as the axis of symmetry, invades the viewer's space and gives depth to a very flat scene; from a symbolic point of view, it is a prefiguration of the future sacrifice of the Saviour. To the right of the viewer, three figures occupy the whole of framework , arranged in height as the only suggestion of depth. They are the Virgin, who in the foreground prepares to receive her son with outstretched arms, with Saint Joseph at her right, and in the background the prophetess Anne as a witness to this extraordinary event in the history of salvation.

This story is a compendium of text and image, which becomes the page of an illustrated bible to be read, with the four paragraphs chosen from Luke 2:22-40's account of this crucial episode of redemption. The extracted verses correspond in total synchronicity with the moment selected here, Jesus in the arms of Simeon, as if it were a vignette of the same. The central panel is headed by a frieze in which the following registration appears on a white background: ECCE HOMO ERAT GERVSALE (M) which, translated, reads "At that time there lived in Jerusalem a man", completed at the bottom by another band, half-hidden from below, which reads: QVI NOMEM SIMEOM, "called Simeon" (Luke 2:25). The precise moment depicted here is recounted in the following text on a correiform cartouche beneath the altar: IPSE ACCEPIT EVM VLNAS SVAS ET BENEDIXIT DEVM ET DIXIT (Luke 2, 28-30), i.e. "he took him in his arms and blessed God, saying...". Finally, at the foot of the scene, in another cartouche of leather on a black background, we find Simeon's song of praise, known as "Nunc dimitis", which appears in the Liturgy of the Hours: NUNC DIMITIS SERBVM SERBVM TVV(M) / SECVNDV(M) VERBVM TVVM IN PACE QVIA / VIDERVNT OCVLI MEI SALVTARE TVVM / QVOD PARASTI ANTE FACIEM OMNIV(M) POPVLORV(M), "Now Lord, you may let your servant go in peace, for my eyes have seen your Saviour, whom you have presented before all peoples" (Luke 2:29-31).

Although Friar Juan de Beauves has left us reliefs that are copies with slight variations of Raphaelesque prints, it is more frequent to extract characters and specific elements from other engravings that he introduces into the new themes, endowing them with invention. The speaking character of his compositions is given by the status and the action of the figures who, with their gestures and attitudes, express their inner world. This is the case of Elcano's presentation , in which the subject of Simeon derives ultimately written request from the High Priest engraved by Dürer in The Marriage of the Virgin (c. 1504), which was copied, like the others in the Marian series, by Marcantonio Raimondi. This model of the priest was adapted by Damián Forment in the presentation of Jesus in the main altarpiece of the Pilar in Zaragoza and in various versions by his disciples in Santo Domingo de la Calzada, Tauste and Barbastro.

Photomontage of Simeon. A. Dürer. Priest, from The Marriage of the Virgin. D. Forment. presentation from the main altarpiece of the Pilar, Saragossa (C. Morte). Elcano. presentation. Lumbier. Circumcision of the main altarpiece.

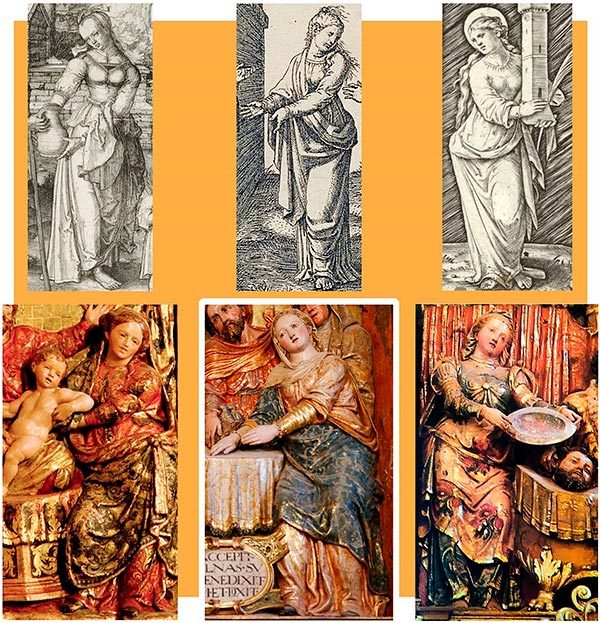

He is improperly dressed in priestly garb to emphasise the status and piety of this righteous man, with overlapping garments, talar costume, sleeveless vestment, ephod and high pointed mitre in the manner of a moon. The subject of the Virgin with her arms in a receptive attitude is repeated in other documented works by Fray Juan, such as the Circumcision of Lumbier, Salome in the submission of the head of Saint John the Baptist in the main altarpiece of Huarte Araquil or Saint Lucia showing the tray with her eyes, in the collateral altarpiece of San Ginés de Irañeta. We also find an extraordinary resemblance to the protagonist, holding a jug, in the engraving of the Repudiation of Hagar by Abraham (1508) by Lucas van Leyden, or various figures by Marcantonio Raimondi that repeat this gesture, such as the allegory of Friendship in the Dialogue by A. Berutti (1517), Saint Barbara in the series of the Little Saints or David with the head of Goliath (1515).

Photomontage of the Virgin. Engravings by L. van Leyden, Hagar, from the Repudiation of Abraham. M. Raimondi, Friendship, from the Dialogue of A. Berutti and Saint Barbara. Virgin. Lumbier. Elcano. Huarte-Araquil. Salomé, from the submission of the head of the Baptist on the main altarpiece.

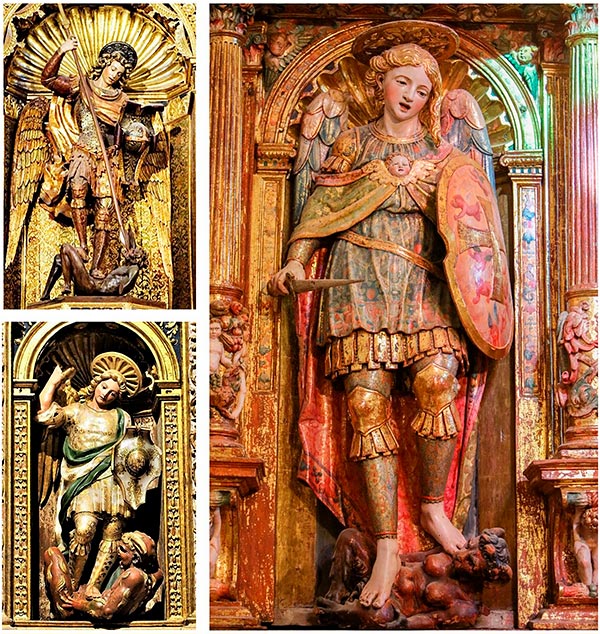

The side altarpiece on the Gospel side is presided over by a beautiful carving of Saint Michael, an expressive work from the 70s of the 16th century which, due to its classicism and beautiful face, reveals the Friar's gouge. It is a singular Renaissance image of one of the most popular iconographies in Navarre after those of Esteban de Obray and Domingo de Segura in Tudela, Orcoyen, Miguel de Espinal in Badostain and before those of Juan de Anchieta in Añorbe and Ambrosio de Bengoechea in Elvetea. Its elegance, which sets it apart from its contemporaries, derives from the last written request of carvings of the archangel made by his master Gabriel Joly, with whom Beauves had trained in Saragossa. His starting point was the main altarpiece for the church of San Miguel de los Navarros in the Aragonese capital (1517-1521), which was followed by other altarpieces for the Seo, Tauste, Bolea and Tarazona, executed between 1520 and 1535. Like the rest of the altarpiece, the main altarpiece has a colourful polychromy from life, applied around 1620 by Fermín de Huarte y Arrizabala († 1626), a painter from Pamplona, with an abundance of gilding and beautiful bouquets, cartouches, pearls and stewed angels in shades of carmine and blue.

Photomontage of St Michael. G. Joly. Head of the altarpiece of San Miguel de los Navarros, Zaragoza, and Saint Michael of the altarpiece of Santiago, collegiate church of Bolea (Huesca) (elviajedelalibelula.com). Elcano. Head of collateral altarpiece.

He is depicted as an ephebe of great beauty in a classical contraposto, protruding from the framework of his niche. This perfect formal finish is accompanied by a moral beauty with Neoplatonic undertones, as his spiritual hierarchy is reflected in his colossal size with respect to the tiny anthropomorphic demon he tramples on, who becomes a mere footstool at his feet. The psychomachy between Good and Evil is further characterised by the contrast between the prince of light and the dark, twisted, satyr-like, horned figure of Lucifer, who symbolises his triumph over darkness. He is dressed in several overlapping garments, which is one of the most common characteristics in the costumes of our artist. He wears a short tunic with a round neck, under which is the leather-strapped skirt of the Roman soldiers and, over it, a cloak worthy of his rank of "prince of the heavenly militia", closed with an angel's head as a brooch. The silver-plated greaves survive from the medieval harness and, as an ornament, knee pads and shoulder pads with fan-shaped loops. His attributes are the wings in the style of classical victories, which protrude behind his shoulders and are tucked in, thus fitting the narrow framework of the niche. He wields the characteristic short rapier at waist level, invading the spectator's space. He is protected by a large oval shield with a cross kicked between brushed angels. We see this same cross in the nimbus of Christ on the main altarpiece in Unzu.

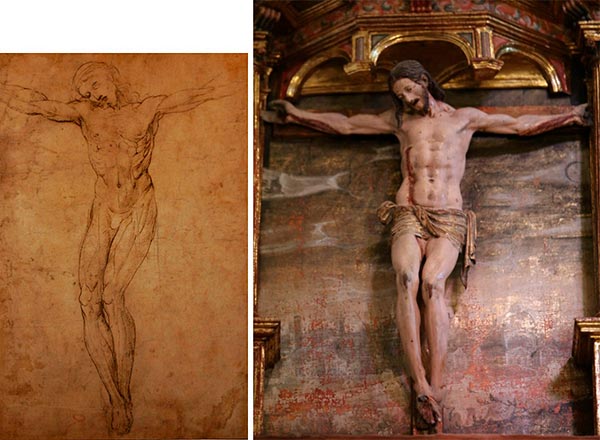

Finally, we will focus our attention on the crucified Christ in the attic of the altarpiece of San Miguel, a beautiful Mannerist image, whose refined carving can only correspond to a master such as Juan de Beauves. We will leave for another occasion the other two expressive crucifixes, the one on the Calvary of the main altarpiece and another dated 1557, which are exceptional in this church. We thus add a new image to the group that C. García Gainza attributed to our artist, with the Santo Cristo de Otadia from his Shrine of Our Lady of Fair Love in Alsasua at the head, another preserved in the church of Zamarce, from the main altarpiece of Huarte Araquil, and the one from the main altarpiece of Irañeta, defining its characteristics in a masterly manner. They are expressive images, but with "more flesh" and size as a Miguelangelesque preamble to Romanism.

Photomontage of the Crucified. Raphael. Study for a Crucifixion. Library Services Marucelliana of Florence. Elcano. Crucifixion from the altarpiece of San Miguel.

The attic of the altarpiece of San Miguel houses a Mannerist crucified Christ. The quality of this piece is enhanced by the canopy with a semi-hexagonal Serlian temple that shelters it. It depicts Christ in agony with his eyes and mouth open and the characteristic tuft of hair hanging at his right hand. The arms are straight and parallel to the crossbar along their entire length, with an elongated eight-headed canon, slightly bent legs and an excellent anatomical study with the muscular planes softened, a quality known in Italy as morbidezza or blandness. The purity cloth is very short, calmly folded and close to the body. It follows a much-repeated outline of a canvas band which is adjusted by crossing the two ends in front, one of them emerging in the form of a pendant on the left hip and the other, puffed out like a knot, on the right side. Its folds are much more fluid than those of the perizonium of the Calvary crucifix in the main altarpiece. The starting point for these Crucifixions is to be found in High Renaissance models created by Raphael and Michelangelo, such as a study by the painter from Urbino, dated 1507-1508 (Library Services Marucelliana in Florence), with a similar arrangement of arms and head and a similar study of muscles and joints, for a Crucifixion that was engraved by the Master of the Dado in 1532.

SOURCES AND BIBLIOGRAPHY

ECHEVERRÍA GOÑI, P. L. and FERNÁNDEZ GRACIA, R., "El imaginero fray Juan de Beauves", Príncipe de Viana, Anejo 12 (1991), pp. 161-170.

GARCÍA GAINZA, M.ª C. and ORBE SIVATTE, M., Catalog Monumental de Navarra, IV*. Merindad de Sangüesa, Pamplona, 1989. pp. 221-222.

GARCÍA GAINZA, M.ª C., "Crucificados del siglo XVI", in El Arte en Navarra, 23, Pamplona, Diario de Navarra, 1994, pp. 360-361.