The piece of the month of December 2021

A LARGE PART OF THE CASE OF THE BAROQUE ORGAN OF THE CATHEDRAL OF PAMPLONA IN GALLUÉS HAS BEEN FOUND.

Alejandro Aranda Ruiz

Historical and Artistic Heritage Delegation

Archbishopric of Pamplona and Tudela

The construction of an organ for Pamplona Cathedral (1740-1742)

Thanks to the data and documentation provided by Sagaseta and Taberna (1985: 268-271) and María Gembero (1995a: 50-53 and 1995b: 353-363), we know very well the construction process of the baroque organ in Pamplona Cathedral - built between 1740 and 1742 -, the artists who took part in its construction, as well as the name of its main commissioner.

The deplorable state of the main organ in the Pamplona cathedral, located in a tribune on the north or gospel side, above the choir stalls in the central nave, led the Cathedral Chapter to agree to the construction of a new instrument in 1740, after years of successive repairs. The offer of the archdeacon of the Chamber, Pascual Beltrán de Gayarre, known for his great liberality in the field of the arts, to "build the organ with its case at his own expense", must have tipped the balance in favour of commissioning a new organ (Sagaseta and Taberna, 1985: 269).

As a hybrid art, the construction of an organ involved music and the art of instrument building on the one hand, and sculpture and painting on the other. The former, i.e. the construction of the musical instrument, was the responsibility of the organ builder position . Many people could be involved in the execution of the case: architects, assemblers, carpenters and sculptors, who were responsible for the design or design of the case and its execution through the carving of the numerous decorative elements and sculptures that adorned these spectacular pieces of furniture. They were joined by the gilder and polychromator responsible for giving colour to the outer casing of the instrument. The close link between the instrument and the case meant that the organ builders demanded the right to build the case as well, something which the carpenters of the Guild of San José and Santo Tomás of Pamplona fiercely opposed (Morales, 2014: 46). Consequently, most of the time it was the masters in charge of making altarpieces and other pieces of liturgical furnishings who undertook most of the organ cases in Navarre (Fernández Gracia, 2011: 139). The partnership between organ builders and carpenters was such that there were even more or less consolidated professional couples who worked as a team, such as the one formed at the end of the 18th century by Diego Gómez, organ builder from Ragusa, and Miguel Zufía, master architect and sculptor.

In the case of the organ in Pamplona cathedral, the commission for its construction fell to two people with close ties to the cathedral and the diocese: Matías de Rueda y Mañeru and José Pérez de Eulate. The former was the nephew and disciple of one of the most outstanding masters of the Lerín organ workshop, José de Mañeru y Ximénez, whom he served for six years as an apprentice and eleven as a journeyman (Sagaseta and Taberna, 1985: 188; Jambou, 2000: 119-120 and 2002: 463; Sales and Ursúa, 2007: 49). position Matías ended up settling in Pamplona, where, like his master, he worked as organ builder or in charge of the maintenance of the cathedral organs between 1732 and 1748 (Gembero, 1995a: 49). As for the second, a native of Legaria, from 1719 he was apprenticed to the prominent Pamplona sculptor Fermín de Larráinzar, whose daughter Juliana he would end up marrying and whose workshop and position as overseer of works for the bishopric he would end up inheriting in 1741 (Fernández Gracia, 2002: 390-391). They were joined in the gilding and polychrome work on the box by Juan Francisco de Ariño (Sagaseta and Taberna, 1985: 269).

By October 1741 the construction of the case must have been completed or at least well advanced, judging by the report of José Díaz de Jáuregui, who gave a broadly positive assessment. Thus, the organ was presented by Rueda in 1742, although the repairs and improvements made to it meant that the work could not be considered completely finished until 1745 (Gembero, 1995a: 52).

The disappearance of the Rueda organ and the fate of its case (1885-1905)

The organ built between 1740 and 1742, and consequently its case, remained in place for over a hundred years. Despite the minor alterations and modifications it underwent, the instrument reached the eighteenth century preserving the essential characteristics of a baroque organ (Gembero, 1995a: 52). However, the cathedral organ eventually succumbed to the new winds that were blowing strongly in the field of the liturgical arts. Thus, in 1885-1888 the Rueda organ was replaced by a new one built by the Roqués brothers of Zaragoza which incorporated part of the eighteenth-century instrument (Sagaseta and Taberna, 1985: 269). As could not be otherwise and as a reflection of the new aesthetic values, the renewed romantic instrument was accompanied by a severe neogothic case in wood of its own colour, built by the cathedral carpenter José Aramburu y Echaide (Alvarado, 1904: 33).

With the dismantling of the old baroque organ, the case of José Pérez de Eulate did not disappear, but, disassembled, it was deposited in the cathedral, where it remained until 1905. That year the Chapter, after the bishop's licence , agreed to sell the remains of the piece of furniture to the parish of Gallués for the 250 pts. that the parish priest had offered. In this place its pieces, combined with others of different origin, were used to build a new main altarpiece. The strange configuration of this altarpiece did not go unnoticed by the authors of the monumentalCatalog of Navarra, who attributed it to the fact that "an organ box that now serves as a main altarpiece" had been attached to the chancel of the church (García Gainza and Orbe Sivatte, 1989: 446). What nothing made us think about was the origin of those pieces: the cathedral of Pamplona.

The baroque organ case from a documentary point of view

While the technical specifications of the Rueda organ are well known from a musical point of view, thanks to the construction contract and the reports issued during the building process, the same is not true of the case which housed it. Although we have tried to find the contract, which must undoubtedly have been drawn up between the Cathedral Chapter and José Pérez de Eulate and in which the characteristics of the piece of furniture were set out, we have not been able to do so. It is indirect sources that provide us with the few data that we have. Thus, in one of the reports that Rueda and Pérez de Eulate commissioned on the organ they were building, it was stated that the case had seven castles to house the exterior pipes (Sagaseta and Taberna, 1985: 269). Indirectly, we also know that not all the pipes on the organ façade were of the so-called "canonical" or ornamental type, but that some of them had a function internship, housing in the façade, for example, the bass pipe, the shawm and an oboe (Gembero, 1995a: 52). Specifically, according to Rueda's project , the registers of the bajoncillo and the clarinet, accompanied by the battle trumpet, were located on the façade, as was typical of the Iberian organ, in the form of an artillery (Gembero, 1995b: 354). The piece of furniture built by Pérez de Eulate was briefly described by the Gallic writer Victor Hugo as "a wide organ case, in the taste of the last century, very rich and very gilded, it dominates the whole choir and does not spoil it. Above it we read a verse which, on the other hand, is inscribed on almost all the organs in Spain: Laudate Deum in chordis et organo. Below is the date: ANO 1742" (Jusué, 2006: 487).

The main altarpiece of Gallués

As indicated above, the remains of the cathedral organ now form the altarpiece of the parish church of Gallués. It is made up of a sotabanco, a bench, a three-aisle body and an attic.

High altarpiece of Gallués, ensemble. Gallués, parish church. Photo: Alejandro Aranda Ruiz.

In the sotabanco, the altar frontal is flanked by two large semi-circular corbels decorated with a cherub's head and garlands of flowers and ribbons, the ends of which fall down the sides of the panel to which the corbel is attached. Each of the corbels and the panel on which they are inscribed are in turn flanked by pinjantes of flowers and fruit topped by angels' heads.

The bench, for its part, has four plaques with scrolls and plant motifs: two at the ends corresponding to the side streets of the altarpiece and two in the centre, framing a 17th-century tabernacle.

The body of streets is the most complex part of the altarpiece. It has a kind of bench divided into three parts, corresponding to each of the streets of the altarpiece, in the middle of each of which there is a corbel. The ones at the ends are triangular in shape and have a cherub's head with a veil at the bottom. Each of the corbels, in turn, rests on a plaque decorated with scrolls and plant motifs. The central street corbel, on the other hand, is circular in shape with an identical design to the two located in the sotabanco, although somewhat smaller in size. These corbels are accompanied by different panels with abundant carved decoration, which takes on a convex shape at the ends of the altarpiece. With regard to the main area of the body of streets, it is worth mentioning the three semicircular canopies with openwork decoration that cover each of the streets, creating a kind of niche for the saints of the altarpiece. The canopies at the ends are topped by coats of arms and the one in the centre by a crest formed by a cherub's head with a scallop and decorated with a cross. The three lanes of the altarpiece are separated by a sort of interlining that is covered with decorations of angels' heads and pinjantes of flowers and fruit. The interspaces that guard the central street are triangular in shape, which gives a certain dynamism to the plan of an eminently flat altarpiece. But without a doubt, the most striking element of the body of streets are the two large telamons or atlantes, placed at the ends of the altarpiece with which they form an angle of ninety Degrees.

High altarpiece of Gallués, detail of the body of streets. Gallués, parish church. Photo: Alejandro Aranda Ruiz.

Above the body of the naves is the attic which, taking the form of a semicircular arch, adapts to the chevet of the church. This part of the machine, like the body of the aisles, has its own bench made up of plaques with the same decoration of scrolls and "ces" that we see on the bench of the altarpiece. Similar decorative motifs, but on a larger scale, invade the rest of the structure, internship , in which we can make out three corbels, the central one semicircular and the triangular ones at the ends, which serve to support sculptures. Another outstanding element of the attic is the canopy that crowns the centre, with a cherub's head on its front and openwork decoration.

High altarpiece of Gallués, detail of the attic. Gallués, parish church. Photo: Alejandro Aranda Ruiz.

The altarpiece is completed with several sculptures. The body of the streets contains Saint John the Baptist in the middle and the Virgin and Child and Saint Peter on the sides. The attic, in turn, houses Saint Vincent with two angels at his feet, flanked by allegories of the cardinal virtues of Fortitude and Justice. Finally, the two large telamons act as pedestals for Saint Raphael and the Guardian Angel, accompanied by two children or angels.

Elements of the Pérez de Eulate box in the Gallués altarpiece.

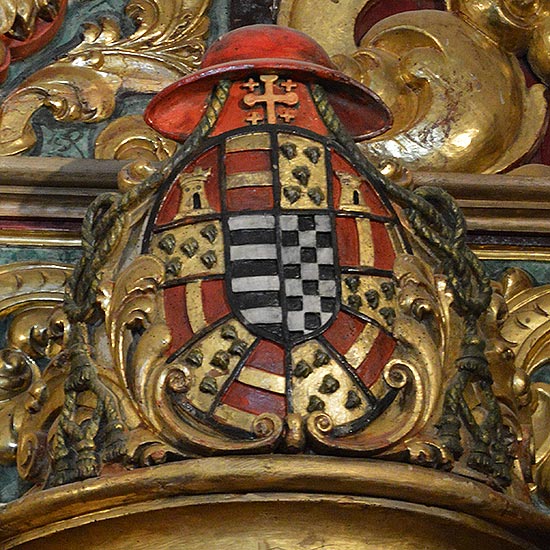

Having seen the elements that make up the altarpiece, it remains to be clarified which ones come from the missing organ case. Although it is not easy to determine exactly which fragments of the altarpiece belonged to the organ and which did not, it can be said that a large part of the Gallués altarpiece is made up of fragments which once formed part of the exterior case of the cathedral instrument. Thus, the eight corbels, the four semicircular canopies, the two large telamons and internship the entirety of the gilded carved decorative plaques and elements belonged to the box carved by Pérez de Eulate. The sculptures of the virtues of Fortitude and Justice, the little angels flanking St. Vincent and the images of St. Raphael and the Guardian Angel with their respective children complement the piece of furniture. Added to all this are the two coats of arms that crown the canopies of the side streets and which correspond to the arms of Bishop Antonio de Venegas y Figueroa, who occupied the Chair of San Fermín between 1606 and 1612.

Coat of arms of Antonio de Venegas y Figueroa, Bishop of Pamplona between 1606 and 1612.

The first thing that catches the eye is the presence of some coats of arms which, because of the way they are made, seem to be contemporary with the other parts of the organ case, but which nevertheless represent the arms of someone who was bishop more than a hundred years before the organ was built. However, as in so many other enigmas related to the cathedral, it is the very erudite prior Don Fermín de Lubián who provides the explanation: "In this Holy Church of Pamplona [Don Antonio de Venegas y Figueroa] made the great organ, whose case had his arms on various parts and when it was increased and renovated in 1742, they were also put back on" (Lubián, 1954: 103). However, in the present case, Venegas's coat of arms is not crowned by the arms of high school de Cuenca de Salamanca - of which the prelate was a collegiate in his youth - as he was accustomed to placing them on the coat of arms and under the hood, but by a sort of Jerusalem Cross, formed by placing four crosses at the angles of a processional cross. This fact did not go unnoticed by the wise prior, who noticed that, in fact, "on his arms were not those of his high school, but those of five crosses in the manner of Jerusalem, and so they were put back, without the cause being clear, because there is no similarity with having been of the committee of the Supreme" (Lubián, 1954: 103). sample Be that as it may, the decision to keep the bishop's arms on the new organ, a decision in which Lubián himself must have played a very active part, is a clear indication of the sensitivity and respect that existed for the report and history of the cathedral and its great men.

The survival of these elements gives us some clues as to what this piece of furniture may have been like, the artistic language it used and its relationship with other Baroque organ cases in Navarre. The surviving documentation allows us to suppose that, although the organ would have been seen from the lateral nave of the gospel through one of the arches of speech of the naves, it had only one façade, the one facing the choir. Like all the organs of its time, the case of the Pamplona church would have been horizontally articulated in two bodies or levels: the first would have served as a base, intended to support the whole structure and house the keyboard built into the case (the window); the second, of greater height and size, would have housed the pipes organised in castles, fields and artillery. Although it is impossible to know what the plan and elevation of the case built by Pérez de Eulate was like, it can be said with some certainty that the elevation of the cathedral organ was T-shaped, with an upper body much longer than the lower body. In this sense, the organ of the cathedral would imitate the structure of earlier organ cases, such as the one in the monastery of Fitero built between 1659 and 1660 or the one in the cathedral of Tudela built in 1671, in which the body for the pipes is longer than that of the keyboard. This articulation made it necessary in the case of the cathedral, as in those of Fitero and Tudela, to establish a transition between the two bodies which, while ensuring the stability of the piece of furniture, would offer a pleasant and harmonious view. In Fitero, this problem was solved by including two sirens which, supported by the ends of the keyboard body, support the upper structure. In Tudela, the transition was made by placing two large scrolls at the ends of the base. In Pamplona, Pérez de Eulate opted for a much more novel solution, using, instead of mermaids or scrolls, a pair of telamons or atlantes with powerful musculature. Taken from engravings of the period, the figures, leaning outwards, hold their hands behind them, holding a cloth with which they cover a large part of their torso. These atlantes, so typical of Baroque architecture, would not only bring the cathedral organ into line with the tastes of the time, but would also end up being imitated. Pérez de Eulate himself again included atlantes in the altarpiece at chapel in the Episcopal Palace, which he made shortly afterwards, between 1748 and 1749 (Fernández Gracia, 2002: 393). Other organ cases built after the one in the cathedral, with which they shared a T-shaped structure, also used the resource of the telamones, such as the one in the organ of Los Arcos built by Diego de Camporredondo in 1759.

Gallués high altarpiece, corbel. Gallués, parish church. Photo: Alejandro Aranda Ruiz.

The eight corbels, on the other hand, indicate that the organ façade combined semicircular and triangular castles. The combination of castles with different floor plans also places the Eulate case in the line traced by organs before and after the cathedral organ, such as those of Santo Domingo de Pamplona and San Miguel de Corella in the 17th century, or Larraga in the last third of the 18th century. These castles were also topped with canopies with carved decoration which, like curtains, partially covered the upper part of the tubes they housed. goal In this case, this characteristic decoration of the castles of Baroque organs was partially carved with the aim of enhancing the sonority of the instrument, as in other cases made around the same time, such as those of Santa María de Tafalla (1735), Lerín (1738-1739) and Villafranca (1739-1740).

High altarpiece of Gallués, telamón. Gallués, parish church. Photo: Alejandro Aranda Ruiz.

The remains that have survived to the present day also allow us to suppose that the organ case of Pamplona Cathedral was covered with a small, nervous decoration, typical of the decorative Baroque style of the late 17th and first quarter of the 18th century. The "caes", scallops, scrolls, cherub heads and the flower and fruit pendants would be distributed along the façade of the piece, often serving to articulate the structure. For example, the pinjantes topped by cherub heads might be placed framing the castles and fields on the façade. It is also possible that part of the carved decoration, located today in the attic and ends of the altarpiece, took the form of finials arranged on the sides of a castle or the box itself, as can be seen in the precedents of Fitero or Tudela. In addition to all this, there would have been a rich sculptural decoration of at least eight sculptures. The arrangement of the arms of the current images of the Fortress, Justice, Saint Raphael and the Guardian Angel suggests that they may once have held some kind of instrument such as trumpets, shawms, cornamuses or violins. class . Likewise, as in other organs, these angels are dressed in a very particular way, as the present-day Saint Raphael and Guardian Angel wear Roman-style breastplates and the Fortress and Justice wear tunics open in the lower half, with a kind of surcoat. These sculptures would be completed with the four examples of children, the two that flank St. Vincent, and those that accompany St. Raphael and the Guardian Angel. Like the former, it is possible that these four little angels could also be carrying an instrument or object in their hands. All of them would be distributed around the organ façade, either among the castles and fields or crowning the whole, and would be, together with the organ, a metaphor for the angelic hierarchies, as Fernández Gracia (2011: 138) points out.

High altarpiece of Gallués, Saint Raphael. Gallués, parish church. Photo: Alejandro Aranda Ruiz.

High altarpiece of Gallués, Guardian Angel. Gallués, parish church. Photo: Alejandro Aranda Ruiz.

SOURCES AND BIBLIOGRAPHY

ALVARADO, F. de [pseudonym of Mariano Arigita Lasa], guide del viajero en Pamplona, Madrid, Establecimiento Tipográfico de Fortanet, 1904.

file Pamplona Cathedral. L.A.C. 5 (4-01-1894/15-03-1906), f. 555.

FERNÁNDEZ GRACIA, R., El retablo barroco en Navarra, Pamplona, Government of Navarre, 2002.

FERNÁNDEZ GRACIA, R., "Contribución de los talleres escultóricos navarros al órgano barroco", in TARIFA CASTILLA, M.ª J. (coord.), Chair de Patrimonio y Arte Navarro. report 2011, Pamplona, Chair de Patrimonio y Arte Navarro, 2011, pp. 138-140.

GARCÍA GAINZA, M.ª C. and ORBE SIVATTE, M., Catalog monumental de Navarra, v. IV*, Pamplona, Government of Navarra/Archbishopric of Pamplona/University of Navarra, 1989.

GEMBERO USTÁRROZ, M., La música en la catedral de Pamplona durante el siglo XVIII, v. 1, Pamplona, Government of Navarre, 1995a.

GEMBERO USTÁRROZ, M., La música en la catedral de Pamplona durante el siglo XVIII, v. 2, Pamplona, Government of Navarre, 1995b.

JAMBOU, L., "Mañeru y Ximénez, José", in CASARES RODICIO, E. (coord.), Diccionario de la música española e hispanoamericana, v. 7, Madrid, Sociedad General de Autores, 2000, pp. 119-120.

JAMBOU, L., "Rueda y Mañeru, Matías", in CASARES RODICIO, E. (coord.), Diccionario de la música española e hispanoamericana, v. 9, Madrid, Sociedad General de Autores, 2002, p. 463.

JUSUÉ SIMONENA, C., "Visión de viajeros sobre la catedral de Pamplona", Cuadernos de la Chair de Patrimonio y Arte Navarro, n. 1. programs of study sobre la catedral de Pamplona in memoriam Jesús M.ª Omeñaca, Pamplona, Chair de Patrimonio y Arte Navarro, 2006, pp. 477-495.

LUBIÁN Y SOS, F., Relación de la Santa Iglesia de Pamplona de la provincia Burgense, ed. by José Goñi Gaztambide, Pamplona, Real Cofradía del Gallico de San Cernin, 1954.

MORALES SOLCHAGA, E., "Sobre la liberalidad de la organería", Ars Bilduma, 4 (2014), pp. 37-47.

SAGASETA ARÍZTEGUI, A. and TABERNA TOMPES, L., Órganos de Navarra, Pamplona, Government of Navarre, 1985.

SALES TIRAPU, J. L. and URSÚA IRIGOYEN, I., Catalog del file Diocesano de Pamplona. Section of Processes, t. XXVII, Pamplona, Government of Navarra, 2007.