The piece of the month of November 2021

"REMEMBRANCE OF THE TREE AND BIRD FESTIVITIES" (PAMPLONA, 1925).

Javier Itúrbide Díaz

Chair of Navarrese Heritage and Art

Tree and bird festivals

The Tree Festival was celebrated for the first time in Madrid in 1896 and three years later in Barcelona. From that time on, it spread throughout the Spanish municipalities. It acquired official status as a result of the royal decree published in 1904 that instituted this commemoration, and became mandatory after eleven years, with the publication of the Royal Decree of January 5, 1915, which provided for its celebration in all municipalities. In order to guarantee its fulfillment, they should include in the annual budgets an item destined to this festivity, with the warning that "the governors will not approve any municipal budget without including in it an item, no matter how small, destined to the indicated purpose".

As for the Bird Festival, it began to have some relevance in 1902, when Spain signed, along with eleven European countries, the International agreement for the Protection of Birds Useful for Agriculture.

In application of all this, the City Council of Pamplona united in 1925 the two celebrations in one workshop dedicated to the "Fiestas del Arbol y del Pájaro" (Festival of the Tree and the Bird).

The party and the snack bag

For this reason, the city council had programmed for Friday, March 20, 1925, the feast of the tree and the bird in which trees would be planted and nests would be placed in the Taconera, Vuelta del Castillo and Ciudadela. The protagonists would be the children of the "schools and private schools" of the city, who would be accompanied by their teachers. The music bands of "La Pamplonesa" and the Regiment of "America" would give a festive air to the activities; for their part, the authorities of the province and the city would enhance the festivity with their presence.

But the day came out with rain, wind and cold, which forced to modify the program: in the morning some trees were planted hastily and the participants were summoned at three o'clock in the afternoon in the modern building of the municipal schools of the place of San Francisco, instead of in the Taconera where it was initially planned. Here the children awaited the arrival of the authorities, who a few minutes earlier had left the town hall in procession to solemnly walk along Mayor and Eslava streets. The deputy mayor, representing the first municipal authority, the civil and military governors, the provincial deputies, as well as representatives of the judiciary, the Chamber of Commerce and Industry, the cathedral chapter and the bishopric.

The civil governor, Modesto Jiménez de Bentrosa, presided over the ceremony. The first to speak was the inspector of teaching Primaria, Eladio García, who encouraged the children to respect trees and birds; he was followed by the deputy mayor, who emphasized the presence of the authorities, whom he thanked for their support for business to instill civic spirit in the citizens of tomorrow.

Then, the assistants, supported by "La Pamplonesa", sang the hymn of the Day of the Tree. Then the children, one by one, approached the presidency to pick up "a bag with a splendid snack", as El Pueblo Navarro described it the following day; it consisted of a chorizo sandwich, a chocolate bar -a donation from the Pamplona factory Subiza-, an orange and candies. In addition, in the bag there were "two little books containing beautiful ideas aimed at instilling in your intelligence the respect for trees and birds", as the inspector of teaching had told the schoolchildren.

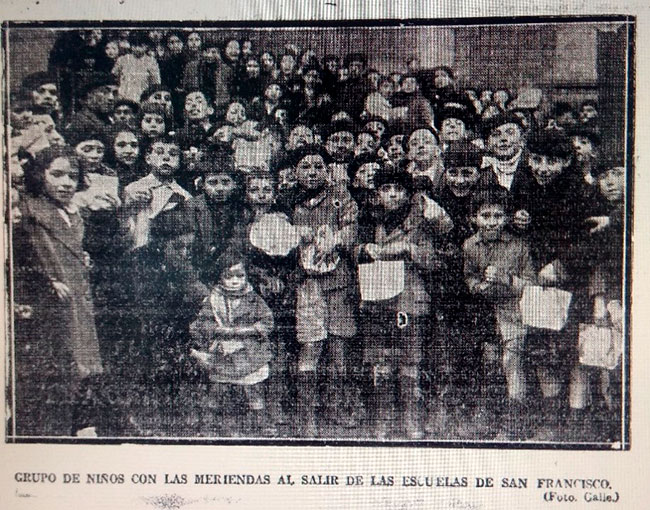

The next day the local newspapers reported the event and the Diario de Navarra and La Voz de Navarra published the photo of the children with their bags. El Pensamiento Navarro had been silent since February 1, when it had been suspended by the military censorship -remember that it was the second year of Primo de Rivera's dictatorship-.

Photograph of the workshop published in Diario de Navarra.

The "little books" of the city council

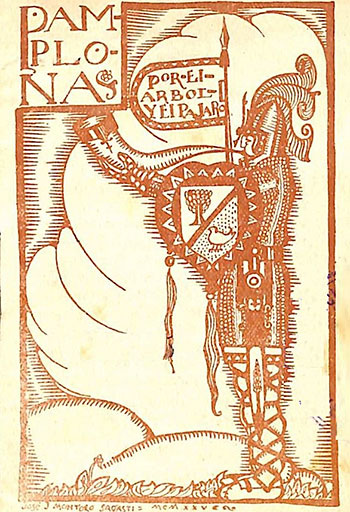

The booklets that the children found in the snack bag were entitled "The Tree and the Birds" and "Juanito and Perico". They were printed on glossy paper of a certain quality, in a soft sepia color, and in two inks: the text in blue and the illustrations, captions and footnotes in sepia. The cover was occupied by a medieval warrior and what could be considered the degree scroll: "Pamplona. For the tree and the bird"; while the back cover featured the printer, "Talleres Tipográficos La Acción Social"; the publisher, the City Hall of Pamplona with the city's coat of arms; and the text, "Souvenir of the Tree and Bird Festivities. Year 1925".

Front and back cover of the "little books" published by the city council in 1925.

The size was small -12 centimeters-, in the style of the stories of publishing house Calleja, which at that time were very popular in the children's literature market. It so happens that in those years his director was Salvador Bartolozzi, father of Francis Bartolozzi (1908-2004), who married Pedro Lozano Sotés (1907-1985), both renowned painters based in Pamplona since the forties of the twentieth century.

The story of "Juanito y Perico" had 19 printed pages with illustrations that had been made for fill in the story. The publication was enriched with a colored paper cover, imitating a flowered fabric, on which was pasted a jagged label with the degree scroll of the story and the author's name.

El árbol y los pájaros", of only ten pages, had the same technical characteristics and reproduced the front and back covers of the "Juanito y Perico" booklet; however, the text lacked illustrations, although it included the coats of arms of Spain, Navarre and Pamplona as they were mentioned. In both cases the binding was with a staple.

"Juanito and Perico"

Juanito and Perico are orphans; first of their father, who had been a lumberjack, and then of their mother, who was torn to pieces by a wolf one bad winter day when she was gathering firewood to heat the house.

After the tragedy, Juanito is taken in as a "servant" by a family in the village. He observes that the birds devour insects and thus protect the crops and, for this reason, he sets about planting trees to give them shelter. Soon his neighbors imitate him, encouraged by his example. As a result, "incalculable wealth is produced in the village, since wood is something that is always worth a lot of money".

One day Juanito picks up a little bird whose nest had been destroyed and which, in spite of his care, dies in his hands. He buries it near his mother's grave and immediately "a magnificent and leafy oak tree" grows up, its branches filled with nests. The prodigy does not end here, because from the trunk comes out "a beautiful young woman dressed in a white dress of diamonds and pearls" that for "several hundred years" remains in that state bewitched by a witch enemy of her father. She is the princess Alondrina -evidently, her name makes reference letter to the lark-, only daughter of king Robus -here the reference letter is to the oak- and, therefore, heiress of the crown. The princess takes the young man to her father's castle, located "millions of miles away", marries him and they live happily "among birds and flowers".

On the other hand, Perico's destiny is tragic: influenced by bad company, he becomes a "naughty boy", who misses school and devotes himself to "breaking plants from trees", picking nests, stoning dogs, as well as not praying "for the soul of his mother devoured by a wolf". Juanito loses track of him until one day a robin tells him that his brother and his depraved friend, who kept cutting down trees and destroying nests, have been devoured by wolves.

For the author, and possibly for children, the repeated references to the ferocity of wolves were not inspired by traditional tales, but by a nearby event: just over a year ago - on December 10, 1923 - the death in Urbasa of the wolf "Aldabidia", which for fourteen years had sown panic in this mountain range and in Andía, had been in the news. More specifically, in the days prior to its hunting by three neighbors of Artaza, it had killed a foal and ten sheep. León Aramburu, the shepherd who put an end to his life, walked through the villages of the Améscoas with his enormous prey - it weighed 50 kilos - and posed before the photographer.

The author of the story

The story was signed Arako, a pseudonym that translated from Basque would come to mean "El de marras", which corresponded to Cándido Testaut Macaya (1885-1956). He was editor of the Diario de Navarra, in which since 1909 he published on Sundays a popular section entitled "Dialogando" (Dialoguing). In his writings he addressed current issues with the language -real and supposed- used in those years by the villagers of the Pamplona basin, who intermingled Basque and Castilian words and constructions to such an extent that they were sometimes unintelligible.

It is considered that his prose has the value of collecting the linguistic transition from Basque to Spanish that popular speech experienced in the region of Pamplona, particularly in the first half of the twentieth century. He had the opportunity to know this oral language largely because of his frequent presence in the villages of the area, where he practiced his great love of hunting and fishing. Two anthologies of his articles entitled Dialogando were published, one dated 1947 and the other expanded in 2003.

It should be noted that in the story of "Juanito y Perico" the vocabulary and syntax adhere to Spanish.

The prologue and its author

Arako 's story was preceded by a prologue, "The tree and its benefits", which occupied page two and was signed by the writer and notary Julio Senador Gómez. Born in 1872 in a village in Valladolid into a family of farmers, he would have liked to be a forestry engineer, but he studied law and passed the notary exams. After working at position in several Castilian towns, he settled in Pamplona, where he died in 1962.

Integrated in the regenerationist current, in the manner of Joaquín Costa, he was a renowned author of several books and articles in the press. Like Costa, he gave priority to the Education of children in a country where illiteracy was still overwhelming.

In the prologue, Gómez went on to enumerate the "benefits" of the tree, which provides shade in summer, firewood in winter, shelter for the bird that cleans the crops, fertilizer for the fields with its leaves, protection from wind and lightning, attracts rain and keeps the hail away. He also gives it a symbolic meaning: "My roots are the support of freedom. My branches, the canopy of justice". It ended with the request that the tree makes to the child: "Behave now as a citizen of a civilized country and do not hurt me or persecute the birds that seek refuge in me".

The illustrations and their author

The story of "Juanito y Perico" is enlivened with illustrations prepared for this edition. They appear on nine of the nineteen printed pages. Three are full-page and the rest are inserted in the text, although at a considerable size.

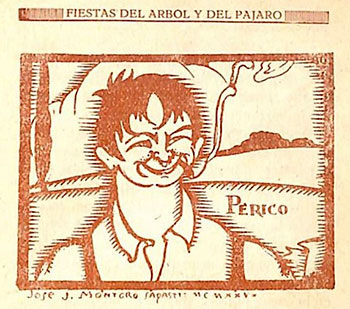

The title page, as mentioned above, is occupied by a warrior holding a spear with a banner on which the degree scroll appears, and a pole illustrated with a tree and a bird (p. 1). The next illustration reproduces the children's village with an idyllic view of a hamlet and a church tower looming behind it (p. 4). This is followed by a portrait of Perico, disheveled and with a cigarette in his mouth (p. 7) ( sample ). Then Juanito appears, handsome and well groomed (p. 11).

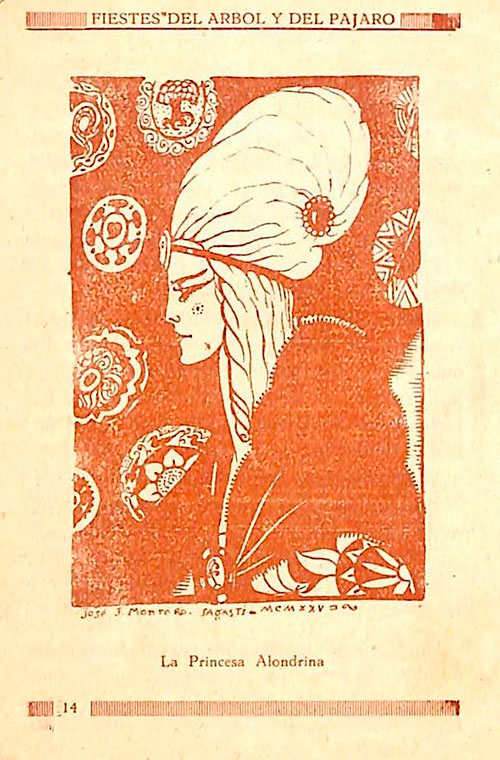

Page 14 is devoted entirely to the figure of Princess Alondrina, depicted half-length, with a sophisticated hairstyle adorned with two brooches; the background is occupied by circles with geometric and vegetal ornaments that could be related to modernism, which was in vogue at that time. On another page, King Robus wears a helmet with a huge plume, like the warrior on the cover, and a dress adorned with circles similar to those on the portrait of Alondrina (p. 15). The third full-page illustration sample shows the castle of King Robus, protected by a drawbridge and a walled gate with a spearman standing guard (p. 16). Next, a coin is reproduced with the effigies of Juanito, in the foreground, and Alondrina; both wear royal crowns "by the grace of God" (p. 18). The back cover, as already mentioned, repeats the motto of the title page: "For the tree and the bird" and is partially occupied by a large tree and a bird with a worm in its beak (p. 19).

The illustrations are made with official document, in one ink, with shading based on parallel lines, as was common in the cartoonists of the time. They have been prepared as a complement to the text and with the necessary expressiveness to capture the interest of children's readers. At the bottom always appears the name of the author "José J. Montoro Sagasti" and the year of execution in Roman numerals: "MCMXXV.

José Joaquín Montoro Sagasti was born in Pamplona in 1898, studied at the Jesuits in Tudela, graduated in Law at the University of Madrid and studied Philosophy and Letters in Salamanca, although he did not finish degree program. At the age of 22 he opened a law office in Pamplona and Tudela, and shortly afterwards he directed the Executive Council of the partitionist towns of the Bardenas Reales de Navarra.

He was a multifaceted man who, apart from his profession, collaborated for more than thirty years, under the pseudonyms Kaskote and Perroganan, in the periodical publications of Tudela; he illustrated works of diverse genres -archaeology, history, literature-; he edited his legal opinions with typographical care; he designed a good part of the coats of arms that adorn the Tudela place de los Fueros; and in Tudela, where he lived, he stood out as an erudite and witty contertulio. Gil Gómez, who has sketched his biography, considers him "a fabulous man". He died in Pamplona in 1976, at the age of 78.

It should be noted that in the twenties of the last century, when photoengraving had not yet taken root in the Pamplona press, there were a relatively large number of quality cartoonists. In the Diario de Navarra, for example, R. Tejedor's pencil portraits of concert performers and lecturers visiting the capital of Navarre were outstanding; Salas was the author of schematic caricatures, in the style of the famous Bagaria; and Garayoa drew pelotaris with ease and a sense of movement. On the other hand, Pedro Lozano collaborated in La Voz de Navarra with illustrations in several columns unrelated to the news published on the page; as for Muro Urriza, he designed decorative covers, and Ciga shone as a poster designer.

The booklet "The tree and the birds".

This brochure instilled in children respect for trees because of their beneficial effects on the countryside and on people. With this purpose examples of good practices in Navarre, Spain, Germany and France were given, while allusions were made to familiar places such as the Vuelta del Castillo and the river Al Revés. Birds were also praised because they protect crops from insects.

On this occasion the message was direct, with positive data , although perhaps not very suggestive for young readers, and consequently there was no room for fables, as was the case in the story "Juanito y Perico".

The author of this brochure was a technician: Pablo Archanco Zubiri (1892-1962) from Pamplona, an agricultural engineer, teaching assistant of the Provincial Agricultural Service and professor at the School of Agricultural Experts in Villava.

On the other hand, he was a Basque nationalist and probably for this reason the newspaper La Voz de Navarra ( 1923-1939), of similar ideology, published his writing in its entirety on the inside pages, although without indicating that it came from a municipal publication. In addition, the day after its celebration, it gave on the front page the chronicle of the Fiestas del Árbol y del Pájaro (Tree and Bird Festivities).

Years later, Archanco was a founding member of Basque Nationalist Action (ANV) and at the beginning of the Civil War he was arrested in Pamplona. He managed to pass to France and in 1938 he went into exile with his family in Argentina, where he died.

In that country he collaborated in various nationalist publications, especially in the official monthly magazine of ANV, Tierra Vasca. Here his name and surname appear, from the first issue, published in Buenos Aires on July 1, 1956, in articles on foral and historical topics.

Recap

For two centuries, printing presses had only taken care of children to provide them with modest printings, with crude typography and bad paper, of course with one ink, destined to the learning in school of the first letters, of notions of mathematics and, above all, of Christian doctrine. They were the popular "cartillas" or "doctrinas", which were printed year after year with large print runs, since their sale was assured by the demand of schoolchildren. In fact, the first printing press installed in Navarre in the 16th century, the one set up by Miguel de Eguía in Estella, printed primers that were sold inside and outside the kingdom.

Since the middle of the 17th century, its sale was monopolized by the Hospital Nuestra Señora de Gracia in the capital of Navarre, which, thanks to these and other school prints, always with a large circulation and strong demand, raised resources for its operation.

It was not until the 19th century that the primers were replaced by modest manuals on geography, history and civics. These books were still fundamentally didactic, sober, not to say arid, aspects that made them unattractive to children's readers.

The two "little books" published at the beginning of the 20th century, whose existence has been mentioned in the preceding paragraphs, represent a change in the Navarre editions aimed at children. Undoubtedly, following the guideline of successful national publications, they offer a suggestive format and typography, diversity of inks and illustrations conceived to support the text and stimulate the reader's imagination. In this case, they had the particularity that they were free of charge, since the city council had published them to encourage children to take care of trees and birds.

In contrast to Archanco's informative text, which due to its content and tone would not appeal to children, Arako's story has chilling passages, where good and evil are clearly defined and the protagonists receive, the good Juanito a prodigious award , and the bad Perico a horrifying punishment.

As for the message addressed to children about the protection of trees and birds, it is fundamentally utilitarian, aiming to obtain immediate material benefits: some bear fruit and the others protect crops. The broader and more altruistic concepts of Nature, Environment or Ecology will take decades to take shape and take root in society.

SOURCES AND BIBLIOGRAPHY

ARAKO (pseudonym of C. Testaut), Juanito y Perico, Pamplona, City Hall, 1925. available in Library Services Navarra Digital(BINADI).

ARCHANCO, P., El árbol y los pájaros, Pamplona, Ayuntamiento, 1925. Copy in the Library Services of Navarra.

CRESPO GALLEGO, H., Recuerdos, data [...] dedicados a la Fiesta del Árbol y de los Pájaros, Madrid, Imprenta Municipal, 1925. available at Library Services Digital. Memoriademadrid.

GIL GÓMEZ, L., Otra galería de tudelanos notables, Pamplona, Diputación Foral, 1978 (Temas de Cultura Popular, 326).

Tierra Vasca. Buenos Aires, 1956-1975. Monthly periodicity. available in Uranzandi digital 1.