The piece of the month of October 2021

AN UNPUBLISHED PORTRAIT OF ESTEBAN JOAQUÍN DE RIPALDA Y MARICHALAR, FIRST COUNT OF RIPALDA

Pilar Andueza Unanua

University of La Rioja

In the Navarre collection of Íñigo Pérez de Rada Cavanilles there is an unpublished portrait of Esteban Joaquín de Ripalda y Marichalar, first Count of Ripalda, dated in the 18th century, which we now present.

Portrait of Esteban Joaquín de Ripalda y Marichalar, ca. 1724-1731.

A life in the service of the Hispanic Monarchy

Son of Antonio de Ripalda y Ayanz de Ureta (Górriz, 1633) and Catalina de Marichalar y Vallejo (Pamplona, 1640), lords of the palace and town of Ripalda, in the valley of Salazar, Esteban Joaquín was born in Górriz in 1665, in whose parish he was baptized. His siblings were the military men Antonio and Luis, knight of Santiago, and Antonia. He belonged, therefore, to a family of the palatial nobility of Navarre whose members - the lords of the palace and place of Ureta, the lords of the palace and villa of Ripalda, and the lords of the house Marichalar de Lesaca - had enjoyed and enjoyed at that time various grants of bedding granted by the monarchs and also the last two estates had, in addition, a seat in the General Courts of the kingdom in the arm of the knights.

As the first-born he succeeded to the family entailed estate and was also chosen as heir by both his father and his mother of agreement with their wills granted in 1685 and 1715 respectively. In this way he was able to enjoy the palace and town of Ripalda, the board of trustees over his church with the power to appoint an abbot, the acostamientos and the call to Cortes, as well as white lands, vineyards and a mill in that town in the Pyrenean valley. He also owned a house in Górriz with its lands, as well as several vineyards in Itoiz and Orbaiz and five houses in Aoiz, where he also had white land. However, despite being a palace owner and enjoying an income, his life was linked to the army, which led him to live a good part of his life outside his native kingdom. The military services rendered by his ancestors and, above all, his support to the Bourbon cause during the War of Succession cemented, as in the case of so many Navarrese of the time, the instructions for his later social and professional progression centered on the service of the Hispanic Monarchy, which allows us to place him within the phenomenon that Caro Baroja called "the Navarrese hour of the XVIIIth century".

Following in the footsteps of his father, who died as an infantry captain, and his paternal uncles, at the age of seven "his parents [...] sent him to the exercises of war in the city of Pamplona". In the Navarrese capital he was a soldier between 1672 and 1682, at which time, at the age of seventeen, he went to the prison of Larache, in Africa, where he served for two years and eight months as an ensign and captain. On his return to Pamplona, in 1687 he captained one of the three companies of his presidio. The conflict that confronted the French and Austrian candidate for the succession of the Spanish throne placed him as colonel of one of the regiments that raised the Cortes of Navarre in Sangüesa to support the Bourbon army on the borders between Aragon and Catalonia. On November 1, 1705 he fought in Fraga with the enemy army led by Antonio Desvalls, where he was seriously wounded with two bullets in the leg.

In spite of that setback, his reputation did not decline, but on the contrary, Philip V granted him in 1708 the encomienda of Molinos and Laguna Rota of the Order of Calatrava. In 1710 he was proclaimed political and military governor of Zamora, position which he occupied until 1724 and during which time he was promoted to brigadier according to the dispatch of June 5, 1719. On March 23, 1724 he reached the pinnacle of his professional degree program and his maximum social prestige when he was titled Count of Ripalda, but also when he was appointed quartermaster general of the army of Andalusia, assistant of the city of Seville and superintendent of the royal revenues of Seville, at the same time that he was granted the field marshal.

The position of assistant, of which he took possession in the Sevillian capital on July 29, 1724, was similar to that of corregidor in other Castilian cities, so that his role was centered on the exercise of royal jurisdiction. His work and his achievements in that position merited an extension in 1727, which allowed him to manage and organize the extraordinary reception that Seville offered the royal family on February 3, 1729, the date on which the so-called Lustro Real (Royal Lustrum) began. In fact, Pedro Alcántara de Arriba dedicated to him the Succinta verídica description of the sumptuous apparatus, which was arranged in the very Noble and very Loyal City of Seville, for the festive entrance of the Catholic Monarchs. On its first page he praised the figure of Ripalda, not only in the service of the royal people but also of the poor, and extolled "his happy government, which has made Your Excellency acclaim him as Father of the Poor. This is not flattery, Sir, because it is so public, that even the children speak of it, a sure sign that they hear it communicated to their parents; and in this I will cease, Sir, so as not to offend your great modesty".

Copy of letter, in which a succinct and truthful description is made of the sumptuous apparatus, which was arranged in the very Noble and very Loyal City of Seville, Seville, 1729. Photo: Library Services Virtual del Patrimonio Bibliográfico.

In relation to his noble degree scroll it should be noted that it was Charles II who granted him a degree scroll of Castile on March 23, 1699 in recognition of the military services rendered by his paternal paternal uncles Lorenzo, Martín, Luis, José, Agustín, and by his own father and his brothers Luis and Antonio, who served mainly in Flanders, in various places in North Africa, Catalonia and in the ocean navy in the last three decades of the seventeenth century. But when 1724 arrived, it was up to Louis I to make the degree scroll official and concrete as Count of Ripalda.

The family kept the royal decree granting the degree scroll as a real treasure: twelve sheets of vellum with the text preceded by the coat of arms of the Ripalda family -three bands and three fleurs-de-lis- and illustrated with the portraits of Charles II, Philip V and Louis I, all bound in crimson velvet adorned with five silver plates on each side: the central one with the family arms and four corner pieces. It had a silver chain with the royal seal. The copy was kept inside a silver box on the sides of which were also carved the coats of arms with the registration: RIPALDA. This box was put in turn in another one lined with red taffeta.

Joaquín Esteban died in Seville on April 9, 1731. The Gazeta de Madrid gave a good account of his death on April 17 (no. 16, p. 64) with the following text: "The Count of Ripalda, his assistant and field marshal of His Majesty's armies, died in Seville on the 10th. In these jobs and in other political and military jobs he had, he showed great zeal and disinterest in the service of the king and the public, for which his death has been greatly felt". The Navarrese was buried in the Professed House of the Society of Jesus, an order to which he was closely linked; not in vain, for example, he had paid for the solemn octave that was celebrated in his church on the occasion of the canonization of St. Aloysius Gonzaga and St. Stanislaus of Kostka between November 13 and 20, 1727.

The funeral honors for the deceased were celebrated in that temple on April 19 and Father Antonio de Solís y Federigui preached in them, who, establishing a parallelism with Saint Esteban protomartyr to structure the sermon, extolled the virtues of the count, especially his piety and commiseration with the poor, emphasizing also his relevant role in the supply of grain to the Andalusian city in times of famine. He closed his speech with some verses of which we highlight the following:

And having given him Navarre (a region almost

Eastern region with respect to us) cradle, he gave him

(in correspondence) Seville, western par- (in correspondence) Seville, western par- (in correspondence) Seville, western par

of Spain, sepulchre, so that from East to West, from the

west, from sunrise to sunset

of the sun to the sunset

and celebrated his heroic name.

Name.

Antonio de Solís, Sermón en las exequias... Del señor Don Esteban Joachin de Ripalda, Seville, Imprenta de la Viuda de Francisco de Leefdael, 1731. Photo: Library Services of the University of Seville.

Not only did Solís act as a panegyrist of the Navarrese nobleman, but in the printed edition of this sermon even the censor himself, graduate Baltasar Pérez de Vargas, praised his figure:

it is the glory of this city to have had as an assistant a subject of such honest prendas that all will serve as rule and rule so that all those who succeed him in the employment will try to watch the correct conduct of his good government. Nor would Seville satisfy with less expression how much it owed to Mr. Ripalda, since there were so many and so many repeated occasions in which he manifested his loving heart, that it will suffice for credit of his love the many that we experienced this year in which without less zeal and affection than his could not have had so much relief, as this town owed to his fineness and care.

Despite having traveled throughout his life in so many places by virtue of his positions and services, it is striking that the last will and testament of Esteban Joaquín de Ripalda was granted in Fraga when he was wounded in 1705. Thanks to this will, his heir was his natural daughter Jerónima, born to Jerónima de Beinza, from Aoiz, unmarried, marital status , which Esteban Joaquín also shared at the time of her birth. However, the child was left under the care of her grandmother Catalina Inés de Marichalar, and her father was in charge of her Education and food. Although in the aforementioned document Ripalda recognized his daughter as such, he had to wait until December 24, 1726 for Philip V to issue a royal decree legitimizing Jerónima. This document allowed her to become the second Countess upon the death of her father, but she could not succeed to the family estate, which was claimed before the courts in 1737 by Joaquín Vélaz de Medrano, Viscount of Azpa, who claimed his rights as a man born of a legitimate marriage as the grandson of María de Ripalda Ayanz de Ureta. In 1724 Jerónima married her relative Juan Luis de Ripalda y Yoldi, a native of Murillo de Lónguida, receiving from her father in the marriage contracts 2,000 silver pesos and the use and usufruct of the goods that he then enjoyed.

Esteban Joaquín did not always remain single; on the contrary, there was a double marriage in the family. He and his sister Antonia married respectively with the brothers Leonor and Miguel de Unda y Garibay, noble neighbors of Viana, whose ancestral home has been preserved in one of the flanks of the place del Coso of this city. Miguel was an important personage, as he would become master of the field, member of the committee of the Indies, of the Treasury and superintendent of the Almaden mines since 1696. From the marriage of Esteban Joaquín with Leonor, a child was born, Jorge, who did not reach adulthood. She died in 1695 in Pamplona.

House of Unda and Garibay, Viana.

The portrait

The painting, an oil on canvas of vertical format and measuring 197 cm high by 104 cm wide, sample , shows Joaquín Esteban full-length, partially turned to his left, with a dignified air and his gaze fixed on the viewer. He presents a firm posture, with a certain envelopment and a face with realistic features. He is dressed in the French style, with the clothing definitively imposed in Spain with the arrival of the Bourbons to the throne, very similar to that worn, for example, by Philip V in the portrait kept in the Museo Cerralbo, by Miguel Jacinto Meléndez, painted in 1712: a showy crimson coat with long skirts up to the knees, studded with buttons and abundant golden embroidery on the front and on the sleeve cuffs; underneath, the white tie with lace trimming and the shirt cuffs, also with lace, can be seen. At the level of the stomach and hanging from a textile ribbon, he displays a circular enameled insignia with gold trim of the Order of Calatrava, a jewel that not only served as an adornment for the knights, but also projected to society an image of nobility and belonging to a privileged and minority social group . It is adorned with a long curly wig that falls in front of the shoulder and a black hat with feather trim and a bow. The attire is completed with white breeches to below the knee, stockings of the same color and black shoes with red heels, model made fashionable by Louis XIV, incorporating colored details and silver buckles.

Portrait of Esteban Joaquín de Ripalda y Marichalar, detail.

Portrait of Esteban Joaquín de Ripalda y Marichalar, detail.

Portrait of Esteban Joaquín de Ripalda y Marichalar, detail.

The portrait, of discreet quality, responds to European courtly models and merely repeats the pose that Hyacinthe Rigaud established in 1701 in his portrait of Louis XIV (Louvre Museum). Thus, the protagonist appears turned three-quarters, with one leg more advanced than the other, looking at the viewer, with the left arm bent at the waist and the right arm resting on an object, in this case the sword, typical of the military official document . Logically here the emblems, symbols and clothing of the royal power that accompanied the Sun King have been suppressed.

In contrast to the aforementioned French portrait and other baroque portraits typical of European courts, in this one the scenographic accessories such as curtains and columns have disappeared to give way to a landscape background with brownish tones and a light that places us in a sunrise or sunset. On this landscape, to the right of the portrayed, and in small size, a war episode is narrated that we believe corresponds to the confrontation that Ripalda had in Fraga with the Austracist army on November 1, 1705 in which he was wounded in a leg, as a person dressed in a red coat lies lying in front of several soldiers in light uniform. This episode should be related to the wound that Esteban Joaquín shows in his right leg. This resource with a secondary scene in the background was already being used in our country in the religious painting of the 17th century. An example is the canvas of San Fermín by Ximénez Donoso preserved in the Royal Congregation of San Fermín de los Navarros, or Christ in the house of Martha and Mary by Velázquez, in the National Gallery of London. And the same happened in history painting where war episodes were narrated, as attested by the paintings of Maíno, Pereda y Salgado, Cajés, Carducho, Leonardo, Zurbarán or Velázquez himself in the Salón de Reinos in El Retiro.

The idea passed to the 18th century, both for popular painting, such as votive offerings, and for portraiture, which placed as a backdrop some scene related to the protagonist. Again, the most eloquent example is the portrait of Louis XIV by Rigaud in the Museo del Prado (1701), where the monarch appears posing in the same way as in the aforementioned example, but now with French armor against a landscape in which a battle is taking place. This concept of portraiture continued, albeit with other nuances, throughout the 18th century. sample For example, to cite a couple of diverse examples, the portrait of Antonio de Ulloa, by Andrés Cortés y Aguilar, where through a window a galleon can be seen in the background that refers to his scientific expedition in America, or the portrait of Sebastián de Eslava, viceroy of New Granada, preserved in the palace of Guendulain in Pamplona, which shows a navy with several ships at his side, thus alluding to the defense of Cartagena de Indias that he led against the English.

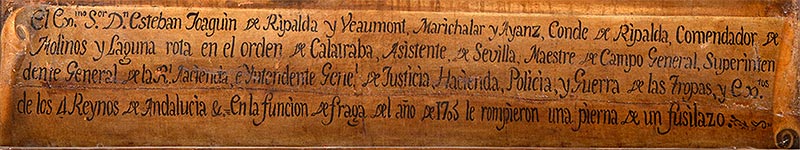

The picture is completed with a registration that appears occupying the whole inferior part on what it pretends to be a rolled up parchment: The Exmo. Dn. Esteban Joaquín de Ripalda y Veaumont Marichalar y Ayanz, Count of Ripalda, Comendador de/ Molinos y Laguna rota in the order of Calatraba, Adjutant of Seville, Maestre de Campo General, Superinten/dente General de la Real Hacienda, e Yntendente Genel de Justicia, Hacienda, Policía y Guerra de las Tropas y Extos/ de los 4 Reynos de Andalucía. In the function of Fraga of the year 1703 they broke a leg of a fusilazo.

Portrait of Esteban Joaquín de Ripalda y Marichalar, registration.

Although the painting may have been painted after the Count's death, and this registration may even have been added after its execution, we are inclined to think that it was painted during his lifetime, between 1724, the year he arrived in Seville, and 1731, the date of his death. Its state of conservation, in need of cleaning to restore its lost luminosity, prevents us from being more precise about its authorship, probably by a painter of the Sevillian school, a school that by that time had lost the brilliance it had displayed in the previous century.

The portrait must have been commissioned by Esteban Joaquín himself in order to send it to his family in Navarra to be present among his family, even in effigy. This demonstrates the great relevance that this pictorial genre acquired among the nobility, through which they proudly displayed the deeds of their members and ancestors in their homes and palaces. According to its current owner, the painting was passed down to the successors of degree scroll for several generations and therefore hung on the walls of the disappeared palace of Ripalda in Valencia. It must also have been exhibited in the palace that the counts had in Alfafar, in the region of La Huerta de Valencia, as attested by a label on the back (ALFAFAR Nº 1), possibly alluding to an inventory. Finally, via inheritance, the portrait fell into the hands of the Counts of Berbedel, whose descendants put it on the antiques market, where it was acquired by Íñigo Pérez de Rada.

SOURCES AND BIBLIOGRAPHY

ANTONIO DE SOLIS, Sermón en las exequias solemnissimas que en la Casa Professa de la Compañía de Iesus se hicieron a la tierna, respetable report de don Esteban Joachin de Ripalda, Conde de Ripalda, Imprenta de la Viuda de Francisco Leefdael, 1731.

file Real y General de Navarra, Tribunales Reales, Proceso 111113: Luis y Jerónima de Ripalda, condes de Ripalda contra Joaquín Vélaz de Medrano, vizconde de Azpa, sobre submission de diferentes casas con sus frutos.

file Real y General de Navarra. Various Notarial Protocols.

Copy of letter, in which a succinct and truthful description is made of the sumptuous apparatus that was arranged in the very Noble and very Loyal City of Seville for the festive entrance of the Catholic Monarchs. Day 3 of February of this year of 1729.

BRAVO LOZANO, C. and QUIRÓS ROSADO, R., "Esteban Joaquín Ripalda y Marichalar, I Count of Ripalda (1668-1731)", Identity and Image of Andalusia in the Modern Age.. Gazeta de Madrid, nº 16, April 17, 1731, p. 64.

OZANAM, D., "Esteban Joaquín de Ripalda y Marichalar", Biographical Dictionary of the Royal Academy of History..