The piece of the month of April 2022

EMBLEMS IN A LATE SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY WATERCOLOR

Eduardo Morales Solchaga

Chair of Navarrese Heritage and Art

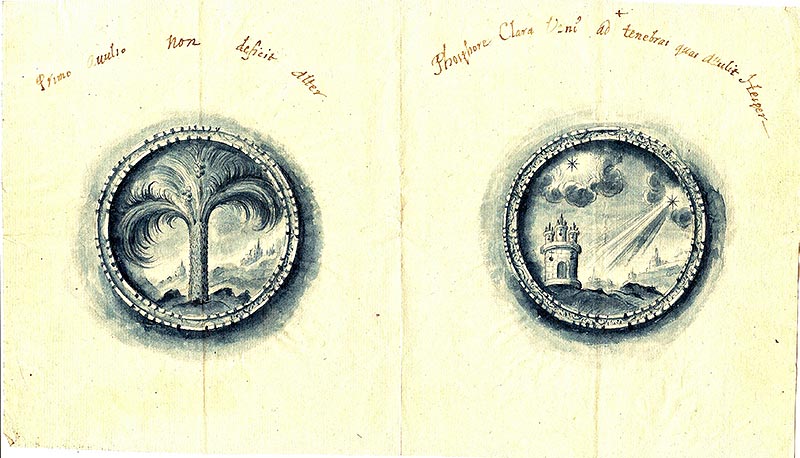

During the centuries of the Baroque, emblematic compositions in which graphic and literary art merged became very important, and all subject of repertoires of companies, currencies and hieroglyphs that offered a cryptic content through an image or picture and a registration or nickname became widespread. Two of them (17 x cm) are preserved in a private collection in Pamplona, executed by hand with a fine blue wash.

Watercolor. Private Collection. Pamplona.

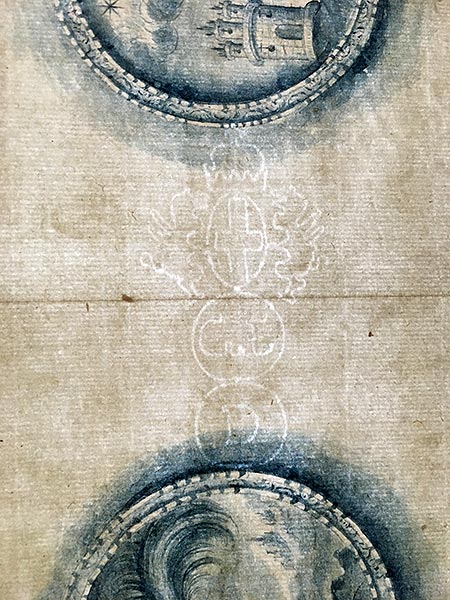

The fragment of paper has a watermark or watermark that links it to a Genoese workshop, as it shows the so-called double circle stamped by a cross with the crown of the republic, flanked by two griffins. Both discs show the initials of the manufacturer (G.E. / D.), which could correspond to the Dongo family (Bartolomeo, Giuseppe and Guglielmo), who had 19 paper mills around the Genoese town of Voltri. In any case, this fact does not imply that the gouache is Italian, since the Genoese workshops supplied paper to the entire West, including Spain, during practically all of Modernity. The morphological similarity with other watermarks preserved in various collections allows us to date the support in a range between 1675 and 1690, when the initials of the entrepreneur and the place of production were added, in the lower circle, the issue of mills that the facility had.

Watercolor filigree.

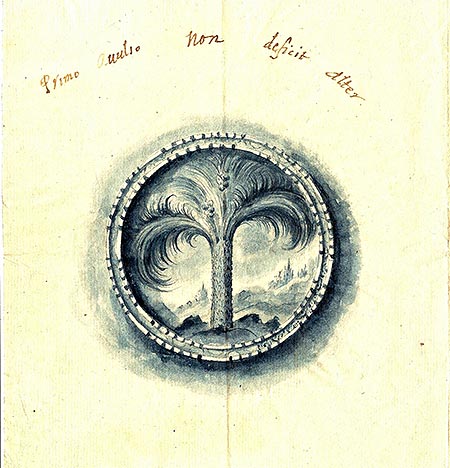

The first emblem sample in a tondo a date palm tree from which two shoots hang. It is located in a sketched space in which in the distance can be glimpsed two buildings on a steep terrain. Above the painting appears the Latin motto "Uno avulso non deficit alter" [When one is missing, another replaces him].

First Emblem.

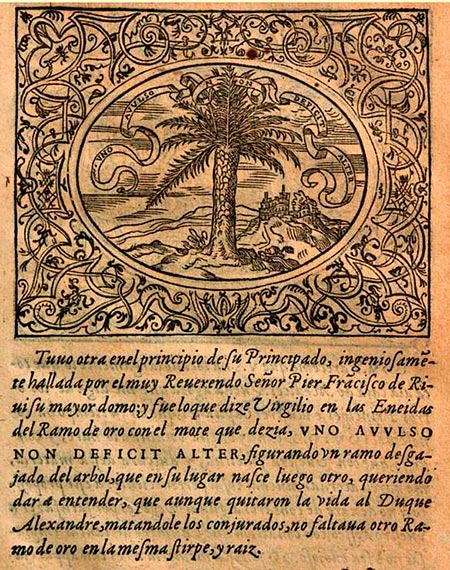

In this case the emblem comes from an early publication of 1552, the Dialogue of military and amorous enterprises. It was written by Paolo Giovio (1483-1552), prolific humanist, bishop of Nocera and physician to Clement VII. In this edition, he associates it with the first years of the government of Cosimo I de' Medici and explains its origin:

He had another [motto] in the beginning of his principality, ingeniously found by the most reverend lord Pier Francisco de Rivi, his steward; And it was what Virgil says in the Aeneids of the golden branch with the motto that said, UNO AVULSO NON DEFICIT ALTER, representing a branch torn from the tree, which in its place is then born another, meaning that, although they took the life of Duke Alexander, killing him by the conspirators, another golden branch was not lacking in the same lineage and root.

Therefore, the motto reference letter refers to the succession made after the assassination of Alexander de' Medici (1510-1537), the last descendant of Cosimo "The Elder", to his cousin Cosimo (1519-1574), the first grand duke of Tuscany. Thus, and following the Virgilian parallelism, when one branch of the family died out, another branch replaced it: a new Cosimo arrived to reedit the old glories of the Medici past.

Emblem in Paolo Giovio's repertoire.

Giovio also mentions the creator of the emblem, Pierfrancesco Riccio (1501-1564), who slightly modified Virgil by replacing "Primo avulso" with "Uno avulso". Be that as it may, the motto of Cosimo I spread rapidly, always associated with the succession, through other repertoires such as the Sententiose imprese by Gabriele Simeoni (1560), the Symbola varia diversorum principum by Anselmo de Boot (1601) or the Devises et emblemes anciennes et modernes by Daniel de la Feuille (1697), among many others.

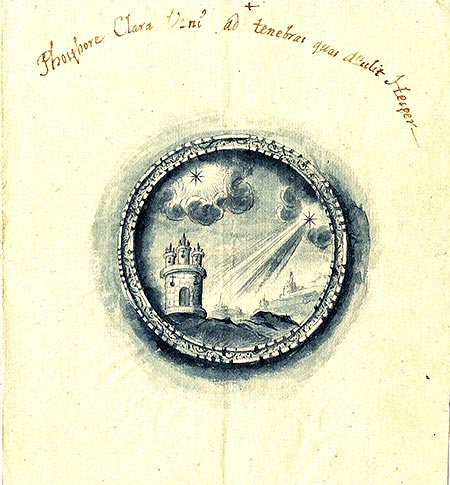

The second motto presents, in a similar place, a watchtower with two stars, one among clouds and the other dissipating them with its radiance. The motto that accompanies the composition reads: "Phosphore clara veni ad tenebras quas attulit Hesper" [Phosphore -dawn star-, come and dispel the darkness that Hesperus -evening star- announces].

Second Emblem.

There is no trace of the mote nor of the pictura in any emblem repertoire, so it is possible that it is an invention of the artist. In any case, it speaks of Venus, morning and evening star, without solution of continuity. Virgil himself in the Aeneid (VIII; 589-591) makes reference letter to this fact with similar words. In some compositions, Venus is taken as a Christological symbol of death and resurrection, as in the Commentaries on the Apocalypse of the Franciscan Alexander of Bremen (1235): "The morning star announces the beginning of the day, just as Jesus Christ rises and brings light to the world"; and in others, mariological, relating it to the morning stella of the lauretan litany, an idea that agrees with the appearance of the tower, as turris davidica or turris eburnea, titles taken from the same composition.

Some renowned emblemists such as Filipo Picinelli (1604-1679) also take the same position. In his Mondo simbólico ( 1653), which collects currencies from various repertoires, he mentions numerous emblems with both symbols: in the case of the tower, he relates it to its protection against enemies, while other compendiums associate it with its role as intercessor, its purity or its maternity.

As for Venus -also called the Morning Star because it precedes the sun or Diana because it announces the rising sun-, it brings multiple meanings ranging from the profane (fulfillment of promises, true love, the true friend, the virtuous or fame after death) to the purely religious (prayer, divine grace, correspondence with God or glory in the midst of ignominy). It also associates it to different contemporary figures (Edward I Farnese or Alexander VII, among others) and to saints of the Catholic Church, such as St. Charles, to whom an emblem was dedicated with a Star emerging among the clouds, or St. John the Baptist, as announcer of Jesus Christ "light among the darkness", together with the Virgin Mary. It also relates the Star to the birth and death of the latter and to her role as inseparable companion of Christ on Calvary.

In this regard, the same author in his Symbola virginea (1694), a publication in which he presents fifty attributes of the Virgin, describes her as "light of dawn", "dispeller of darkness", "rising dawn", "polar star" and, finally, as "luminous Hesperus", making reference letter with this symbol her role as intercessor for the dying. In Spain, the Carthusian father Fray Nicolás de la Iglesia, in his Flores de Miraflores ( 1659), introduced an emblem under the nickname Aurora Consurgens, accompanied by the following composition: "There must be no darkness/ at the time that rises/ this sacrosanct aurora". In the same sense, the German theologian Antonio Ginther (1655-1724), in his two Marian repertoires, emphasizes its character of aurora (Illuminat et eliminat) and evening star, which accompanies the sun (Jesus) until his death(Sequitur deserta cadentem).

Be that as it may, it is difficult to find the ultimate reason that moved the anonymous author of the piece to choose and watercolor both emblems in the same composition, extracting one of them from a well-known publication and probably inventing the other. At the same time, it is strange that political references are mixed in the first one, with others of Christological or Mariological character in the second one. The only point in common of both currencies is the cyclical character and continuity reflected in their meanings, but perhaps it was chance itself that determined the structure followed in their realization.

SOURCES AND BIBLIOGRAPHY

BALMACEDA, J. C., La contribución genovesa al development de la manufactura papelera española, Málaga, CEHIP, 2004.

BLANCO, E., "La imagen del castillo: un tópico religioso y político en la Emblemática del siglo XVII", in Literatura emblemática hispánica. conference proceedings del I Simposio Internacional, La Coruña, 1996, pp. 329-341.

ESCALERA, R., "Emblemática mariana. Flores de Miraflores de Fray Nicolás de la Iglesia", in Imago, n.º 1, 2009, pp. 45-63.

FAHY, C., "Paper Making in Seventeenth-Century Genoa: The Account of Giovanni Domenico Peri (1651)," in Studies in Bibliography, vol. 56, 2003/2004, pp. 243-259.

LÓPEZ DE ATALAYA, A. M., "Los emblemas cristológicos y marianos del P. Antonio Ginther", in conference proceedings del I Simposio Internacional de Emblemática, Teruel, high school de programs of study Turolenses, 1994, pp. 739-750.

LÓPEZ HERNÁNDEZ, I., "Turris Davidica, Turris Eburnea: la fortificación como alegoría inmaculista", in El sol de occidente: sociedad, textos, imágenes simbólicas e interculturalidad, Almería, Universidad de Almería, 2020, pp. 328-342.

PICINELLI, F., El Mundo Simbólico. Los cuerpos celestes (libro I), Zamora, high school de Michoacán, 1997, pp. 301-308.

SPARROW, J., "Pontormo's Cosimo il Vecchio, a New Dating," in Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, vol. 30, 1967, pp. 163-175.