The piece of the month of August 2022

HEALTH, ART AND PROPAGANDA. NICOLÁS ARDANAZ'S PHOTOGRAPHIC REPORT ON THE ALFONSO CARLOS HOSPITAL (1938).

Pablo Larraz Andía

PhD in History of Medicine

The Pamplona photographer Nicolás Ardanaz Piqué (1910-1982) is well known for his costumbrista images, a faithful reflection of the Navarrese society of his time. Within his oeuvre as a whole, we will focus on one of his most outstanding and singular graphic reports, both for its subject matter and for the circumstances in which it was taken, and on which various aspects will be dealt with.

As soon as the civil war broke out, on July 19, 1936, Ardanaz left as a volunteer requeté with his brother Antonio with the Column of Colonel García Escámez towards the Madrid front, then still to be defined. During the following months he would act as link for the Command, a period that he would also take advantage of to develop his photographic facet, obtaining numerous images of the war and life in the field. Several of them were published in Diario de Navarra and, more occasionally, in El Pensamiento Navarro. Unfortunately, in spite of its historical value, it is a dispersed collection of which only a minor part has reached us.

From the artistic point of view, some of his most dynamic and spontaneous images correspond to this vital period, assuming certain technical and aesthetic risks that are unusual in his later production as a whole. Although he was already showing certain preferences and aesthetic patterns, his photographs exuded a freshness and versatility in keeping with the agitated reality he was witnessing and starring in.

Within his war photography, we will focus on a specific report clearly differentiated from the rest; at the beginning of February 1937, Nicolás or "Ceneque" -as he was known at the front- enjoyed a few days of leave in Pamplona. During this short stay, possibly at the initiative of the Carlist newspaper El Pensamiento Navarro, he made an extensive and complete photographic chronicle of the Alfonso Carlos Hospital, a health center of enormous dimensions and capacity established by the Carlist Central War board in the building of the Nuevo seminar of Pamplona.

The reportage was most probably carried out in several conference, during bright mornings in which the remains of the snow that had fallen on the city a few days earlier could still be seen. From the format of the images, we know that he used at least two cameras -among them his favorite, the Rolleiflex- and in some of them he had the help of a tripod and a second person. financial aid .

His intention was to capture in the goal of his camera the operation and activity of the internship totality of services and rooms of the hospital, as well as to highlight its symbolism and Carlist identity. His photographic tour covered the rooms in the three pavilions of the building, as well as the cloisters and interior courtyards, the entrance and exteriors, the basements and even the terrace and the roof.

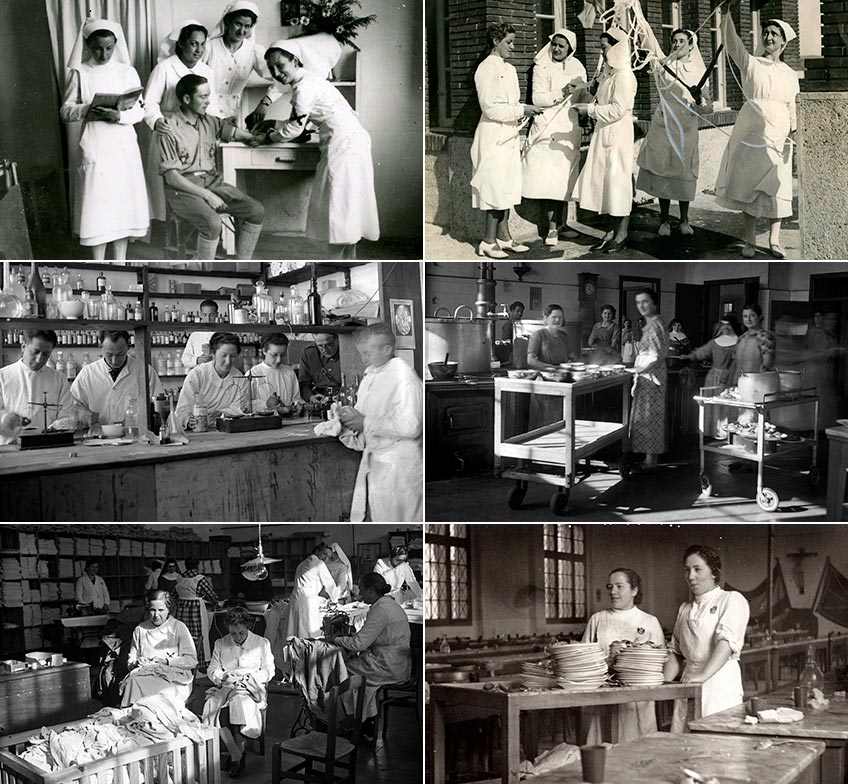

In his pathway -undoubtedly advised- he went through all the rooms portraying the complexity and laboriousness of the different services that made up the center. The images convey a sense of order, cleanliness and intense dynamism. In most of them, the female protagonism stands out: nurses making cures, bandages or writing down the doctor's instructions; pharmacists preparing medicines; technicians making or developing X-rays; seamstresses repairing and ironing bed linen and clothes for the wounded; cooks in full activity; the volunteers in the offices preparing files and records...

Other photographs, more sequential, show the operation of the laundry services - disinfection, washing, repair, ironing and storage of clothes - and the dining room: from the preparation and distribution of the food on the long tables and the blessing by the chaplain, to the young volunteers collecting the dishes after the meal.

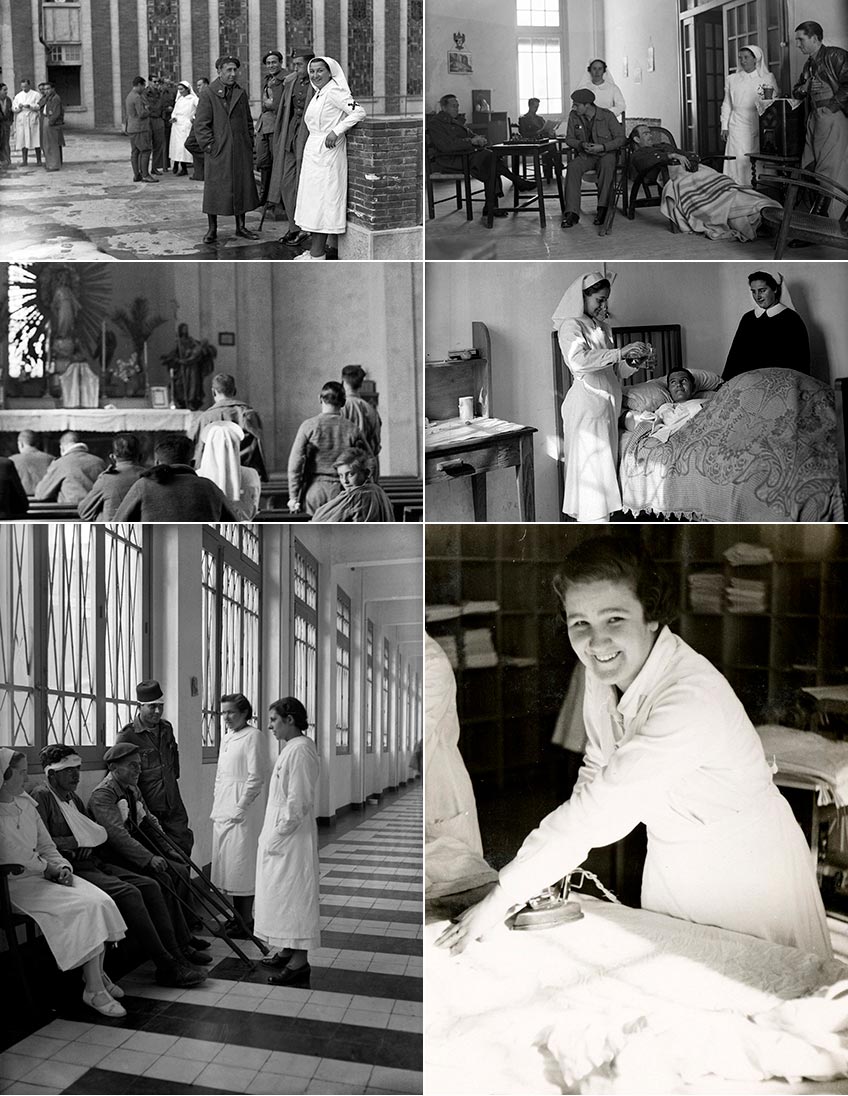

We also find more relaxed scenes, generally dedicated to the presence of the wounded: soldiers strolling along the terraces of seminar, sitting in the cloisters of the building enjoying the winter sun, reading books or newspapers, writing letters, playing cards and chess or praying in the chapel.

Other images show an atmosphere of coexistence and cordiality between staff and the hospitalized. In them, and in the gestures of their protagonists, a cheerful image is transmitted, of optimism and serenity typical of the convalescent hospital; a space theoretically far from the hard life of the front that, for the wounded combatant, represented rest and security.

In a more intimate tone, we also find beautiful close-ups of young volunteers in the midst of their work: nurses bandaging a soldier's head, pouring him a glass of water or putting him to bed; office workers typing documents; seamstresses concentrating on their sewing machines; or assistants, first laying out and then rolling up clean bandages for a new use.

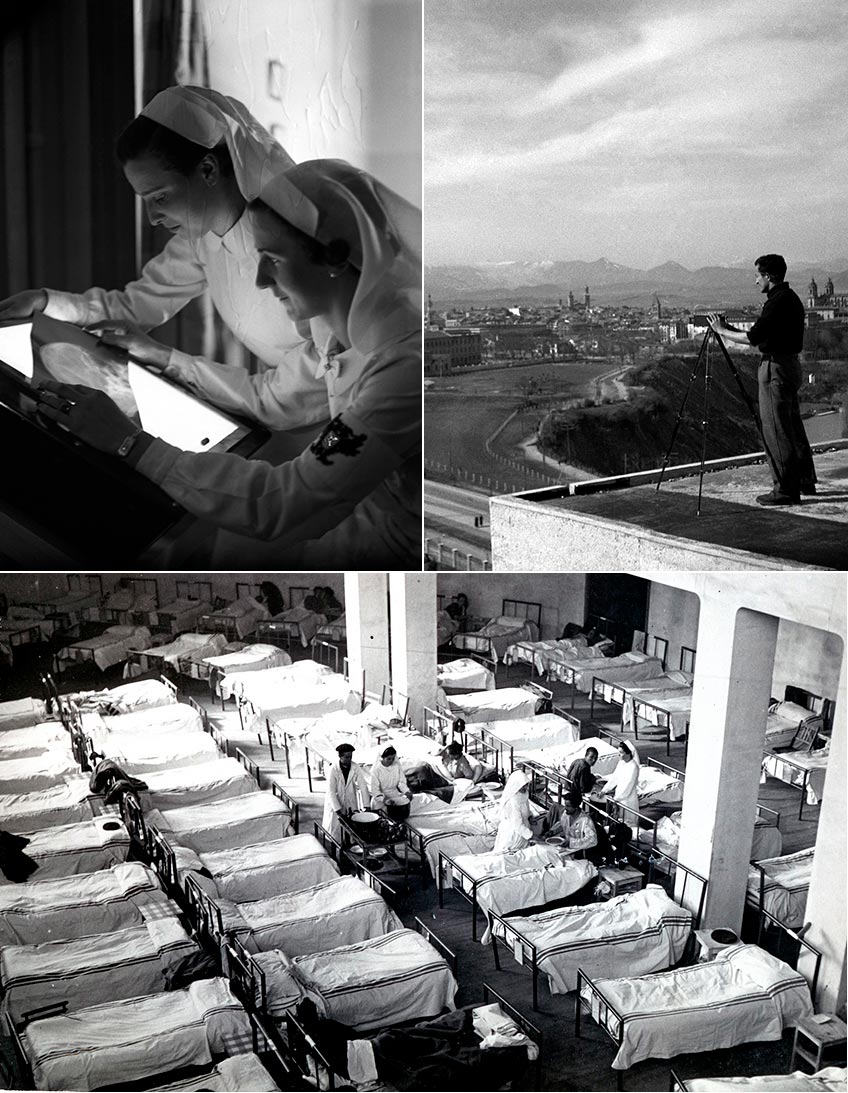

From the artistic point of view, several images of a certain technical complexity and aesthetic beauty stand out B . Perhaps the best is an avant-garde close-up of two nurses looking at an X-ray in the glare of the screen. Its careful composition, the framing and the contrast of lights make it an extraordinary photograph.

Also noteworthy are some scenes in height, climbing the large cross that presides over the building, or the one obtained in the classroom of programs of study -then enabled as conference room "Tercios de Navarra" - with a surprising perspective possibly achieved from a staircase.

Ardanaz also found an opportunity for one of his favorite subjects: the self-portrait. There is evidence of at least two of them: a close-up inside a room, dressed in his requeté uniform; and the one taken from a distance on the terrace of the building. In a scene reminiscent of later mountain self-portraits, Nicolás appears next to his machine on a tripod, seated on the cross of seminar observing the panoramic view of a Pamplona in incipient expansion.

In a similar context, some of the profiles made on the terrace of Eusa's imposing building, with her sister Eleuteria -pharmacist in the center- and her younger brother, Juan, as protagonists, could be catalogued in a similar context. Also noteworthy are the group portraits of nurses taken next to the windows of the building's terrace.

On another level, Nicolás Ardanaz would dedicate one of the mornings to taking individual portraits ID card size to staff of the center, in a small room set up as a studio. In batches of three, undoubtedly in order to save photographic film and printing paper, he would end up passing in front of his camera part of the female staff of the center. Many of the images, cropped, would be used in official nursing cards.

More studied, and with subtle propagandistic intent, we also find elaborate scenes of perfect framing and intended symbolism. Always in the background, but perfectly defined, we see coats of arms and emblems that reaffirm the unmistakable Carlist identity of the hospital: posters, double-headed eagles of the Requeté, painted panels in the wards or bracelets worn by nurses with the embroidered cross of Burgundy.

In this same sense, the forced portrait of Princess Isabel de Borbón-Parma -sister of the Carlist regent Don Javier- acting as a nurse while she seems to bandage the arm of a wounded man with scarce skill . This is the most corseted scene of the whole.

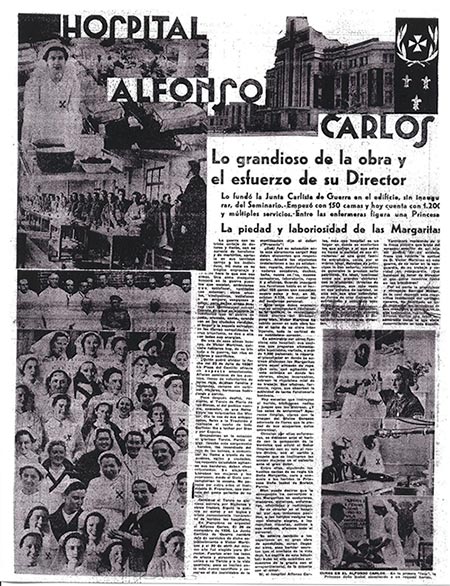

The report sought to show the potential of the Carlist movement in the rearguard, the involvement and dynamism of its women, as well as to document the exemplary operation of its "flagship hospital"; All these aspects, together with the provision of modern scientific and technological means - as well as the voluntary, altruistic and interclassist character of its staff-, made it the ideal mirror through which to show the world the "goodness" of the social model advocated by Carlism, something that previously, and by other means, the Carlist movement had already applied with relative success between 1873-1876 around the Irache Hospital and the figure of Queen Margarita de Borbón-Parma. It was on that occasion the antidote against the "black legend" fed by national and international opposing media, which branded Carlism as a fanatical, reactionary movement, contrary to all progress.

For this purpose, traditionalism had at that time some illustrated newspapers, although its means of propaganda, after the Unification, were more and more controlled. On different occasions throughout 1938, El Pensamiento Navarro would dedicate to the hospital colorful full-page reports, profusely illustrated with photographs of Ardanaz's report. In several of them -as we know from the copies with which they were made-, someone close to the newspaper wanted to emphasize the symbolic charge of the photograph by drawing in pencil the Burgundy Cross on the breasts of the nurses who appeared.

She would also publish colorful collages made from the individual portraits of nurses she had made, accompanied by texts highlighting the role of the daisies in the rearguard. Due to the style and subject matter of the articles, the author of these compositions could very probably have been Lola Baleztena, a prominent Pamplona daisy also dedicated to propaganda tasks.

(click on the image to see full size)

Unfortunately, most of the original images that made up the extensive report seem to have been lost forever. Within the photographic collection of Nicolás Ardanaz deposited in the Museum of Navarra, 23 black and white glass plates corresponding to it, of great quality and in perfect state of preservation, are guarded. Of the vast majority of celluloid negatives we do not know the whereabouts or if they are preserved.

Most of the images that, in very unequal quality, have come down to us, have been thanks to positive copies scattered in the private albums of former nurses -some deposited in the Museo del Carlismo- and to the remains of the disintegrated photographic file of El Pensamiento Navarro. Between them, together with several scenes published in the Carlist newspaper and of which, for the moment, no positive copies have been located, we could estimate around 250 photographs that made up that extraordinary report.

Some images of great documentary value; possibly the most extensive and complete graphic chronicle of a war hospital that was made during the civil war of 1936 in both sides. Also of great artistic interest, being able to sense a Nicolás Ardanaz -at his 27 years old- capable of a dynamic and expressive photography, already possessing a technique B and with an aesthetic that sometimes bordered on avant-gardism. However, we can sense aesthetic and thematic preferences that, in the future, would mark his own style, a reflection of the traditional Navarre that he knew, lived and felt as his own.

SOURCES AND BIBLIOGRAPHY

file Sagüés del Castillo family.

file Eleuteria Ardanaz.

file Alecha family.

file Jaurrieta family.

file General of Navarre. Photographic collection Félix Maiz.

file Larraz-Sierrasesúmaga.

Museum of Navarre. Photographic collection Nicolás Ardanaz.

Museum of Carlism. Photographic collection Alfonso Carlos Hospital.

ARTIGAS, D., "Ardanaz, en la Guerra Civil española", Contraluz, Pamplona, Agrupación Fotográfica y Cinematográfica de Navarra, 1999.

CÁNOVAS, C., "Nicolás Ardanaz, el file fotográfico de un solitario", Catalog Nicolás Ardanaz. Photographs, Pamplona, Museum of Navarra, 2000.

LARRAZ ANDÍA, P. and SIERRA-SEGÚMAGA, V., La cámara en el macuto. Fotógrafos y combatientes en la Guerra Civil española, Madrid, La Esfera de los Libros, 2018.

LARRAZ ANDÍA, P. and SIERRA-SEGÚMAGA, V., Requetés. De las trincheras al olvido, Madrid, La Esfera de los Libros, 2010.

LARRAZ ANDÍA, P., Entre el frente y la retaguardia. La Sanidad en la Guerra Civil: el Hospital Alfonso Carlos de Pamplona, 1936-1939, Madrid, conference proceedings, 2004.

ZUBIAUR CARREÑO, F. J., "Catalog de Miradas. La Navarra que fotografió Nicolás Ardanaz", in FERNÁNDEZ GRACIA, R. (coord.), Pvlchrum. Scripta varia in honorem M.ª Concepción García Gainza, Pamplona, Institución Príncipe de Viana, 2011.