The piece of the month of April 2023

A NEW MONUMENT FOR A RENOVATED PARISH. THE DISAPPEARED HISTORICIST MONUMENT OF HOLY WEEK OF THE CHURCH OF SAN NICOLAS IN PAMPLONA MADE IN 1902.

Alejandro Aranda Ruiz

Cultural Heritage

Archbishopric of Pamplona and Tudela

1. A photographic testimony

If photography is an extraordinary tool for the knowledge of heritage in general, it is even more so in the case of intangible heritage and samples of ephemeral art in particular. One sample of this is the photograph of the old Holy Week monument of San Nicolás de Pamplona, taken by Roldán e Hijo at the request of the parish "as a gift to the lady who gave the monument, to the architect, etc.". Despite this information, the parish file is silent about the photographed monument, so it is the press of the time that allows us to document the work.

According to La Avalancha ( 23/03/1910: 69), the monument was promoted by Francisco Guillén y Lara in the framework of "the different and important works done in this church during the time he has been parish priest". position The design, on the other hand, was the work of the architect Ángel Goicoechea and the material execution was carried out by the Pamplona workshops of Florentino Istúriz e Hijos. Financed by Juana Almándoz, widow of Aroza, the monument was inaugurated on Holy Thursday 1902.

2. Description and analysis of the work

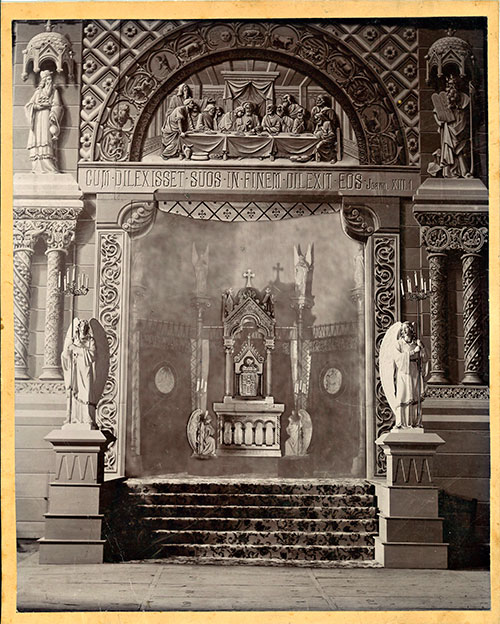

Well, as shown in the photograph and described in La Avalancha, the monument consisted of a large "removable" building made up of two parts: the frontispiece of wood or painted fabrics on iron frames, which simulated the stone facade of a Romanesque church, and the interior of the monument itself, delimited by curtains and presided over by the templete destined to house the reservation Eucharist.

The façade was organized around a semicircular portal. In the tympanum, a representation of the Last Supper, surrounded by the symbols of the 12 Tribes of Israel "sculpted" in the voussoirs of the arch with the Mystic Lamb on the Book of the Seven Seals at core topic. This ensemble rested on the lintel of the door in which, in a frieze, appeared the sentence taken from chapter 13, verse 1 of the Gospel of St. John: Cum dilexisset suos in finem dilexit eos, 'having loved his own, he loved them to the end'. The façade was flanked by two pairs of columns with richly carved crests, capitals and shafts. On the columns were placed, placed under canopies and as simulated statues, a high priest of the Old Testament (Melchizedek or Aaron) on the left and Moses with the Tablets of the Law on the right. Although it is not visible in the photograph, the façade culminated in a pediment or gable roof crowned by a cross. Finally, the access door to the interior was preceded by a staircase flanked by two pedestals with sculptures of angels lampadarios.

Photograph of the monument of San Nicolás taken in 1902 by Roldán e Hijo.

Photo: file Parroquial de San Nicolás.

The interior was formed by a polygonal dais with columns topped by sculptures of angels with attributes of the Passion at its four corners. Between the columns hung damask curtains with two medallions with the Mystic Lamb and doves with the sun of the Eucharist, respectively. The interior space of the monument was articulated around a carved wooden templete, erected in the center of the dais, which housed a matching tabernacle. This set of shrine and tabernacle sat on a pedestal as an altar with the front formed by a gallery of arches topped by the quotation taken from Isaiah 45, 15: Vere tu es Deus absconditus, 'truly God is hidden in you'. The temple was guarded by the carvings of two kneeling angels.

From the stylistic point of view, the monument was a very sui generis reinterpretation of the Romanesque style. The then called "Byzantine style" was also present through the simulation of noble materials such as ivory, marble and gold seen in the altar, the shrine and the tabernacle. In this sense, the monument is situated in the Romanesque-Byzantine line of other productions of the author, the architect Ángel Goicoechea (1862-1920), who had previously directed the works of the atrium of the same parish (1889-1891) and had conceived the project basilica of the Castillo de Javier, erected between 1896 and 1901 (Larumbe, 1990: 563-579). Thus, many aspects of the monument emulate the forms used in these works, such as the paired columns supporting an arch, the interlacing of the column shafts, the decoration of coffers or the internship of placing sculptures on the crests. In any case, the monument was intended to recreate the aesthetics of the Middle Ages average; hence, for example, the interior was intended to evoke the medieval altars surrounded by curtains supported by columns and reproduced and reinterpreted by historicist authors of the nineteenth century, such as Augustus Pugin (1812-1852) or Viollet-le-Duc (1814-1879). The latter included in his Dictionnaire raisonné de l'architecture some designs of altars with curtains supported by columns topped with angels with attributes of the Passion. Be that as it may, the commissioning of the monument was not an isolated event, but, as La Avalancha points out, it was placed in the context of the "different and important works done in this church" that had as their purpose refund the medieval splendor to the parish temple and behind which was Ángel Goicoechea himself. These works not only affected not only the church itself, but also its furnishings, which included the main altarpiece in 1905, the baptistery in 1909, the Immaculate Heart of Mary collateral in 1913 and the pulpits in 1914 (Martinena, 1978: 20-23).

If the piece had -and has- among its functions that of serving as a place for the solemn reservation of the Eucharistic species consecrated on Holy Thursday, it is not surprising that, from the iconographic point of view, the monument was a glorification and exaltation of the Eucharist. Thus, the representation of the Last Supper alluded to the Missa in Coena Domini of Holy Thursday, at the end of which the Blessed Sacrament was transferred to the monument, as well as the quotation of the Gospel of St. John, which was read in the Gospel of the Mass of that day. Aaron or Melchizedek, priests of the Old Testament, are prefigures of the Eucharist itself and of the priesthood of Christ. Moses would make reference letter to the old covenant surpassed by the new, personified in Christ and summarized in his commandment of love, highlighted in the registration of the door. The 12 Tribes of Israel could be an allusion to the earthly genealogy of Christ. In the interior, the sun with the doves and the Mystic Lamb would refer to the Eucharist and its sacrificial character. The registration of the altar table would be an explicit reference letter to the real presence of Christ in the Eucharistic species. Although following the liturgical customs still in force at that time, the monument was to be a symbolic representation of the tomb of Christ(monumentum); the tabernacle no longer takes on the traditional form of a sepulchral urn or casket, but that of a simple tabernacle, anticipating what the liturgical reform after Vatican Council II would mandate in this regard. The presence of the angels with attributes of the Passion surrounding the tabernacle reflected in a visual way the link as the same sacrifice between the Eucharist, whose institution was celebrated on Holy Thursday, and the Passion and death of Christ on the cross, which was commemorated on Good Friday and in whose liturgical function the priest consumed the form reserved in the monument the previous day.

Typologically, this work belongs to the so-called perspective monuments, also known as deep nave monuments (Calvo and Lozano, 2004: 107), consisting of a succession of painted canvases that, combined with fabrics and appropriate lighting, simulated architectures with perspective, like a stage set or theatrical scenery. Inherited from the Baroque, this typology was reinterpreted with a historicist taste at the beginning of the 20th century, when there was a resurgence of this subject of monuments. In the case of that of San Nicolás, the composition formed by a central vain with the Last Supper, and the quotation of the Gospel of St. John below and the figures of Melchizedek/Aaron and Moses on the sides, must have pleased the painter Francisco Sánchez, who reproduced it in a neo-Baroque style for the monument that in 1918 he made for the parish of Lerín (Aranda, 2015: 347-351).

3. The authors and the principal

If the design of the work corresponded, as we have said, to Ángel Goicoechea, its material execution was carried out by the Pamplona workshop of Florentino Istúriz e Hijos. Founded in 1868 by Florentino Istúriz, the business continued active until 1949 through his son Fermín and his grandsons Pedro María and José Ignacio (Rodés, 2021: 172-174). The workshop specialized in religious imagery and in the production of altarpieces and liturgical furniture, reaching notable levels of quality. Thus, Florentino and Fermín were in charge of the construction of all the structural and architectural elements of the monument. On the other hand, the set of sculptures formed by the two angels of the door, the two adorers of the tabernacle and the four of the columns must have been acquired by the Istúriz family in the well-known workshops of "El Arte Cristiano" of Olot, judging by the seal that sample one of the angels preserved today.

Angel made by Talleres "El Arte Cristiano" of Olot for the old monument of San Nicolás.

Photo: Alejandro Aranda Ruiz.

We do not know the cost of the work, since it was paid for by Juana Almándoz y Apecena, a native of Sorauren and resident of Paseo de Sarasate. Her husband, Pedro Aroza y Argonz, a native of Izalzu, remarried her and died at the age of 83 in 1899, leaving several pious orders. His widow, who died in 1932 at the age of 84, must have stood out for her generosity, especially with the parish of San Nicolás, which in 1913 she gave the Immaculate Heart of Mary as a gift. Precisely on the occasion of the inauguration of this altarpiece, the local press referred to her as "the philanthropic and pious Vda. de Aroza" (El Eco de Navarra, 29/05/1913: 2). We do not know the involvement that the donor may have had in the creative process, but the context seems to indicate that it was reduced to paying for a commission that the parish priest and the architect were to lead.

4. Rise and fall of scenographic monuments in the first half of the twentieth century.

In spite of the popularity that this subject of monuments still enjoyed, already then the first voices against them began to be raised, like that of the Aragonese painter and partner habitual of La Avalancha Ramiro Ros Ráfales, who in 1903 criticized, among other things, the anachronistic style of some constructions that tried "to imitate more or less ancient styles, moderately sensible, improper, most of them, to express the main idea" or the ugliness of reproducing complete buildings inside a church, in which behind them there was a lack of "a defined and luminous sky"(La Avalancha, 08/04/1903: 2). The deterioration due to their use, the change of sensibility and the liturgical and religious environment of the mid-twentieth century put an end to the use of these complex machines of which hardly any remains have come down to us. Curiously, when in the 1940s the baroque and historicist constructions began to disappear, some authors, such as Ángel María Pascual, remembered them with nostalgia, lamenting the destruction of those "old monuments of [Holy] Thursday, those that raised their great and bombastic fiction painted under gold dust"(Arriba España, 21/03/1940: 1).

SOURCES AND BIBLIOGRAPHY

file Parroquial de San Nicolás (APSN). Sacramentales, Book 11º de difuntos (1888-1914), f. 115r.

APSN. Sacramentales, Book 13º de difuntos (1930-1941), f. 43v.

APSN. Accounts of the board de Fábrica, no. 2 (1887-1902), f. 227r.

El Eco de Navarra, n.º 1.018, 29/05/1913, p. 2.

La Avalancha revista ilustrada, no. 361, 23/03/1910, pp. 67 and 69.

ARANDA RUIZ, A., "Una obra de Francisco Sánchez Moreno en Lerín: el monumento de Semana Santa de 1918", in Andueza Unanua, P. (coord.), report 2015, Pamplona, Chair de Patrimonio y Arte Navarro, University of Navarra, 2015, pp. 347-351.

CALVO RUATA, J. I. and LOZANO LÓPEZ, J. C., "Los monumentos de Semana Santa en Aragón (siglos XVII-XVIII)", Artigrama, n.º 19 (2004), pp. 95-137.

ECHEVERRÍA GOÑI, P. L., "Los monumentos o perspectivas en la escenografía del siglo XVIII de las grandes villas de la Ribera estellesa", Príncipe de Viana, n.º 190 (1990), pp. 517-532.

LARUMBE MARTÍN, M., El academicismo y la arquitectura del siglo XIX en Navarra, Pamplona, Government of Navarra, 1990.

MARTINENA RUIZ, J. J., "Las cinco parroquias del viejo Pamplona", T.C.P., n.º 318 (1978).

PASCUAL, A. M., "Deploración. Remembering the old monuments", Arriba España, n.º 1.346, 21/03/1940, p. 1.

RODÉS SERRALBO, T., Talleres retablistas e imaginería sacra contemporánea en Pamplona y su Cuenca (1890-2018), Sevilla/Pamplona, publishing house Universidad de Sevilla/ EUNSA, 2021.

ROS RÁFALES, R., "On Art. The monuments", La Avalancha illustrated magazine, n.º 194, 08/04/1903, p. 74.