The piece of the month of August 2024

AN EXCEPTIONAL HISTORICAL TESTIMONY: THE PORTRAIT OF THE CORELLAN CAYO ESCUDERO IN GOLILLA COSTUME

Alejandro Aranda Ruiz

Archbishopric of Pamplona and Tudela

Heritage Culture

Among the many treasures that make up the Arrese collection in Corella, the piece we now bring to your attention deserves special consideration. It is a small photograph, made using the albumen paper technique, in which a portrait of a member of the Corella elite of the 19th century appears: Cayo Escudero Marichalar (1827-1900).

Born in Corella on April 22, 1827, he was baptized a few hours after his birth in the parish of San Miguel. Following the custom of the time, he was given the names of the saints of the day: Cayo and Sotero. To them were added those of Ruperto and Ramón, the former possibly in honor of his maternal grandmother and godmother of baptism, Ruperta San Clemente Montesa, from whom he would inherit the degree scroll of lord of the palace of Eransus. Once he obtained the high school program in Law at the Central University of Madrid in 1849, his life was always linked to politics as a member of the Progressive Liberal Party and since 1897 as a member of the leadership of the Liberal Party of Navarre. In Corella he was elected councilman in 1859, 1861 and 1863. He also occupied the position position of first deputy mayor when he was chosen by the town council constituted on January 1, 1869. A little more than a month later, he appears in a municipal plenary session of the Executive Council as mayor of Corella (10/2/1869). A wealthy and well-connected man - in 1871 he was one of the fifty largest taxpayers in Navarre - he became senator of the Kingdom for Navarre on multiple occasions between 1871-1872, 1881-1884 and 1886-1890. He died in Corella in 1900.

At first glance, it may seem exaggerated to describe a simple photographic portrait from the second half of the nineteenth century as a treasure. However, the value of this photograph lies not so much in the exceptionality of the medium or technique used, in the originality of the composition or in the personality of the portrayed person, but rather in what is represented in it: a Navarrese alderman dressed in the traditional golilla council costume. It is true that there are numerous documentary testimonies of how Navarre's municipal representatives dressed up to the 19th century. We even have a drawing of an alderman from Pamplona from around 1817 preserved in the Municipal file of the Navarrese capital and, what is even better, with the priceless testimony of the oil painting by Juan José Nieva (1823-1890) which, also belonging to the Arrese collection, represents the alderman from Corella, Inocencio Escudero. This albumen, therefore, would be added to these two graphic representations, with the particularity of being to date the only photographic testimony that we know of an alderman in golilla costume.

Portrait of Cayo Escudero, albumen paper, 1860s. Corella, Arrese collection.

Well, the image sample on a neutral background shows Gaius Squire seated and slightly turned towards the camera. The choice of this pose is by no means arbitrary, since his seated position is intended to project the auctoritas inherent to his position councilor and to the lineage of his person. This also contributes to a grim and serious facial expression, with his eyes fixed on the viewer to whom he seems to direct an inquisitive gaze from eternity. The character wears a black velvet doublet with wide slashed sleeves whose openings reveal the lining. The throat is imprisoned by the characteristic golilla collar that gives its name to the costume as a whole, formed by a square cardboard structure with rounded corners, lined with lace or glued fabrics. The short breeches, stockings and shoes with silver buckle that Don Cayo probably wore and that can be seen in the portrait painted by Juan José Nieva around the same time that this photograph was taken cannot be seen. The costume is complemented by a cape, with whose laps the sitter covers his legs. The design of this last garment is striking, as it seems to be fastened only at the back, behind which a rigid rectangular collar is visible, reminiscent of that of the judicial and academic robes or the ferraiolo and ferraioletto of the ecclesiastics. Due to its characteristics, it could be a herreruelo or ferreruelo employee by other authorities of the Ancien Régime, such as the oidores of the committee Real de Navarra. The use of the cape was consubstantial to the golilla, its shape and length depending on the character of the personage. Thus, from a lawsuit of 1819 between the doctors of Tudela and the high school of Lawyers of Pamplona, we know that the lawyers wore the golilla with a long cape, without sword and with lace frills on the sleeves, while anyone who was not a general, lawyer or advocate wore it with a short cape and long sword. In this sense, it is worth mentioning the absence of the so-called "golilla sword", which was also obligatory with the costume, to the point that some town councils even acquired them at their own expense, such as Cintruénigo in 1798 or Arguedas in 1800. This absence can be explained either by Escudero's status as a lawyer or by the fact that it fell into disuse at the time the photograph was taken.

Juan José Nieva. Portrait of Inocencio Escudero, oil on canvas, mid-nineteenth century. Corella, Arrese collection. Photo José Luis Larrión.

Like Inocencio Escudero, the sitter holds in his left hand white gloves that match the lace cuffs that finish off the sleeves of the doublet and which were also worn by other 19th century Navarrese aldermen, such as those of Pamplona. We do not know if these white cuffs had the category of "vuelillos", about which the municipal secretary of Pamplona reported around 1830 that "in the past there was a lot of label about wearing vuelillos, but nowadays everyone wears them". Cayo's wardrobe is completed by the two signs of municipal authority par excellence in Navarre: the rod of command and the veneration. Regarding the first attribute, this was granted to the aldermen of Corellan by the General Courts of 1624 as an element that would serve to identify the councilors in the exercise of their functions, thus ensuring the "better government and administration of justice and authority of the same town". Consequently, Gaius holds in his hands a very fine rod, similar to the one that Innocent also carries in his painted portrait. In the same way, the concession of the degree scroll of city to Corella in 1630 encouraged its representatives to adopt in 1655 the insignia of the veera, in imitation of what other cities like Pamplona (1600), Tudela (1621), Estella (1621), Olite (1630) or Tudela (1621) were already doing, Olite (1630) or Tafalla (1639), and which would later be followed by other towns such as Sangüesa (1628-1688), Cascante (1692), Los Arcos (1798), Valtierra (1798), Arguedas (1800), Puente la Reina (1802) or Mañeru (1819). However, the venera worn by Escudero corresponds to one of the gilded silver ochavados made in 1848 by the Madrid silversmith Mariano Roche, which came to replace its gold predecessors of 1655.

For all these reasons, this photograph is an excellent testimony of the appearance that the regidores of Navarre must have had until well into the 19th century. The golilla has its origins in the reign of Philip IV, who in 1623 imposed it by means of a pragmatic as an alternative to the costly gorgueras of the nobility. What began as an imposition, to which the king himself was obliged, ended up being accepted very willingly by all subjects of any rank, including the members of the main institutions and organizations of the Monarchy. The ambassadors of the Catholic Majesty paraded this costume throughout the courts of Europe, which ended up turning the golilla into the Spanish national costume. Its austerity and the envious position that it forced its wearers to adopt contributed to spread and consolidate abroad the image of the Spaniards as serious people with a cocky character. As part of the Hispanic Monarchy, Navarre was no exception and, in fact, the golilla ended up being the "official uniform" of numerous civil corporations, such as the town councils of the heads of the merindad, cities and towns of the kingdom. Thus, both the members of the Council of the Kingdom and the municipal aldermen were obliged to wear it at their own expense on any occasion when they were exercising their duties, whether in chapter sessions or in public functions. Despite its extraordinary popularity, the new airs brought by the Bourbon dynasty from 1700, added to the enlightened spirit of the Age of Enlightenment, made the nobility began to abandon this garment in favor of the so-called "military suit", "tie" or "colored", which projected their wealth and position better than a nondescript black suit. Consequently, since the 18th century, the golilla, previously worn by a large part of the population, was restricted to certain positions in the administration, such as the members of the royal councils and courts and, of course, the town councils. However, the latter, largely made up of local elites, also began to relegate this garment even in public functions, as seen in Pamplona, Tafalla or Cintruénigo. In 1744, the Cortes of the kingdom even proposed its replacement in the assembly by a black military suit. This situation finally led the Cortes themselves to save this peculiar attire by establishing by law in 1795 that "precisely the same suit [of golilla] should be worn by the mayors and aldermen of all the other republics of the kingdom, who have a seat, voice and vote in the Cortes Generales, in all those public and ceremonial acts to which the town council attends". The law of the Cortes of 1795 brought with it a revitalization in the use of the golilla by the town councils of Navarre. In spite of this, the 19th century will be the time when the definitive withdrawal of this garment will take place, starting with the capital, which will agree to replace it with the more comfortable and modern tailcoat in 1842.

However, some towns in Navarre, whose living forces were less permeable to novelties, continued to use the golilla costume during a good part of the nineteenth century, as is the case of Tudela, which, after a temporary withdrawal of the garment, agreed to recover it in 1865 as a ceremonial costume. The same can be seen in Corella, where the town council continued to use this garment even in 1864, as can be seen in the certificate that attests to the inauguration of the Casa de Misericordia (15/8/1864). Therefore, the portrait of Cayo Escudero constitutes an irrefutable test of how the Corella regiment, faithful to tradition, conserved this secular garment well into the 19th century.

Regarding the authorship and chronology of the photograph, there are several possibilities. Beginning with the author, there is neither signature nor a stamp on the piece that explicitly reveals its authorship, so there are two hypotheses. A first possibility is that the image was taken by the French photographer Leandro Desages, who, as documented by María Jesús García Camón, in 1861 opened a photography studio in Pamplona with Domingo Dublán. In August 1864, Leandro was commissioned by the Diputación Foral to take a portrait of King Francis of Assisi, his entourage and the provincial deputies on the occasion of the monarch's stay at the baths of Fitero. On that occasion, the consort of Isabel II also visited Corella, where he was received with great pomp by the municipal corporation to which Cayo Escudero belonged as a councilman since 1863. The presence of Lesages in the area could be taken advantage of by other relevant local personalities, such as Escudero, who with his colleagues in the corporation received the sovereign in golilla costume.

The second hypothesis is that the authorship of this albumen corresponds to the Corellan Nicolás Andueza Allué (1829-1900), documented by Ricardo Fernández Gracia in Corella since the early 1860s and who may have learned his official document from the aforementioned Leandro Desages, like other Navarrese photographers. If so, this portrait would be added to the two photographs documented by Fernández Gracia, unlike those which do not present any stamp subject to corroborate what we propose here.

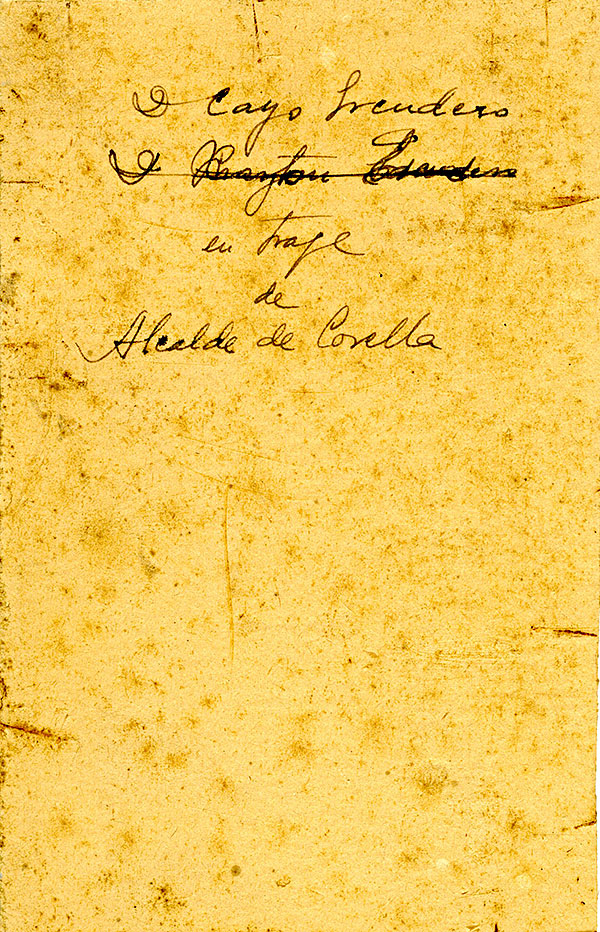

Portrait of Cayo Escudero, reverse. Corella, Arrese collection.

Continuing with the chronology, a handwritten grade on the back indicates that the portrait corresponds to "D. Cayo Escudero en traje de alcalde de Corella" (D. Cayo Escudero in the costume of mayor of Corella). We do not know when he could have held the position of mayor, since, as we have seen, the municipal conference proceedings are silent on the matter and only mention the personage in this position in a plenary session of the Executive Council of 1869, shortly after being elected deputy mayor. The wielding of a rod in his hand tells us nothing about it, since we know that, at least until the nineteenth century, this insignia was not exclusive to the mayor, but common to all the aldermen of Corella. Not in vain, Inocencio Escudero, who according to Carlos Villanueva was not mayor either, also carries a rod in his portrait, catalogued in his day by José Luis Arrese as "portrait of Don Inocencio Escudero. In the costume of mayor of Corella". Be that as it may, if the photograph sample shows Don Cayo as mayor or deputy mayor, 1869 would be the most probable year of the snapshot. If we ignore the handwritten grade and if we stick to what is contained in the municipal conference proceedings we consider that Escudero appears as a councilman, we could extend the chronological arc to the whole decade of 1860. It is surprising, however, that a liberal, heir to those 18th century enlightened ones who had so harshly criticized the golilla, would proudly portray himself dressed in this manner. It is quite possible that in this field, more than his political ideas, his feelings of belonging and identity to a social and political community to which the use of the golilla was linked weighed more heavily.

SOURCES AND BIBLIOGRAPHY

file Municipal de Corella. Book of conference proceedings 13, conference proceedings of the days 1/1/1859, 1/1/1861, 1/1/1863, 15/8/1864; book of conference proceedings 14, conference proceedings of the days 1/1/1869, 10/2/1869.

file of the Senate. Personal Exps., HIS-0152-07.

ARANDA RUIZ, A., Dressing authority. Attributes of power and municipal representation in Navarre, Pamplona, Chair de Patrimonio y Arte Navarro-Universidad de Navarra, 2021.

ESCUDERO, D., "Señores de Eransus, padres y hermanos (siglos XVI-XIX). Coat of arms and paintings of the Palace", Cuadernos del Marqués de San Adrián: revista de Humanities, n.º 12 (2020), pp. 111-146.

FERNÁNDEZ GRACIA, R., "A photographer to rediscover in Corella: Nicolás Andueza (1829-1900), Diario de Navarra, 7/4/2024.

GARCÍA CAMÓN, M. J., "Leandro Desages y Domingo Dublán, primer estudio fotográfico en Pamplona (1861-1881)", Príncipe de Viana, n.º 280 (2021), pp. 657-719.

URQUIJO GOITIA, M., "Cayo Escudero Marichalar", in Real Academia de la Historia, Diccionario Biográfico electrónico.

VILLANUEVA SÁENZ, C., "D. Inocencio Escudero ¿en traje de alcalde de Corella", Revista Peña El Tonel, 2016, pp. 15-18.

VILLANUEVA SÁENZ, C. and VILLANUEVA SÁENZ, R., "Fiestas reales en Corella. visit del rey D. Francisco de Asís, esposo de Isabel II", Programa oficial de fiestas de Corella, Ayuntamiento de Corella, 2014.