The piece of the month of December 2024

A GAS STATION DESIGNED BY VÍCTOR EUSA:

THE VICENTE MUNÁRRIZ GAS STATION ON GUIPÚZCOA AVENUE IN PAMPLONA.

Pablo Guijarro Salvador

Chair of Navarrese Heritage and Art

Víctor Eusa (1894-1990) is one of the most outstanding Navarrese architects of the twentieth century, perhaps the most, since his style staff and innovative style is added to the enormous Issue of his production, around a thousand works, almost all located in Navarra and, more specifically, in Pamplona, to the point of defining the urban image of the capital. subject His more than fifty years of creative activity include all kinds of projects, from churches and residential buildings to less common ones such as parks, hotels, cemeteries, bank offices and, at least, a gas station.

Gas stations, as a new architectural typology, appeared in the 1920s and 1930s, as the number of automobiles increased. Until then, fuel was supplied through isolated pumps linked to garages, workshops and other businesses. Gas stations had several pumps and could provide workshop, greasing and washing services for vehicles, as well as toilets, a store and catering for the driver and his companions. In Spain, these more complete facilities were called "service stations".

In the absence of previous architectural references and being linked to an element as representative of modernity as the automobile, gas stations were used to try out novel solutions that would have been difficult to find in larger projects. One of the most striking aspects of their designs was the roof, in the form of large, light and daring canopies that protected the driver from inclement weather. At first, the formal repertoire that emerged from the imagination of architects and engineers gave rise to a variety of examples, all different from each other, in different styles, with Rationalism being the most widely accepted. However, from the 1950s and 1960s onwards, there was a tendency towards standardization, with homogeneous service stations in which ease of construction and large signs advertising the owner's brand were the main features.

When Vicente Munárriz opened his service station in 1939, there were only three similar establishments in Pamplona, located at place general Mola -currently Merindades- (Unsáin), avenida Zaragoza near the Paúles (Jesús Díaz Martínez) and in this same avenue at the exit of the city (EDSSA), later known as "La Milagrosa". In addition, fuel was supplied by means of several individual dispensers on public roads and in private installations located inside premises. At that time some five thousand vehicles were circulating in Navarra: the last enrollment granted that year was issue 5 094.

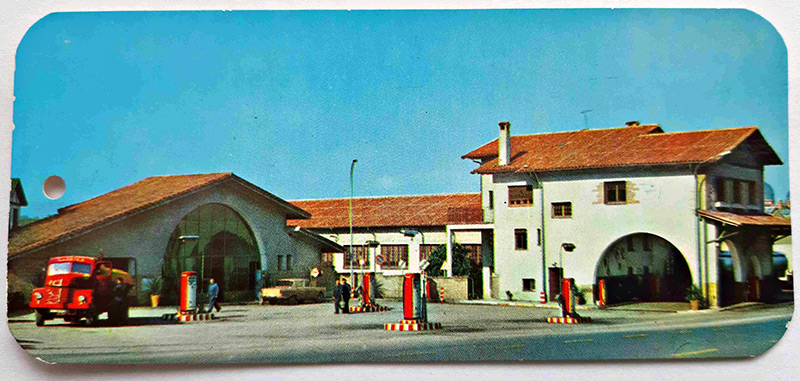

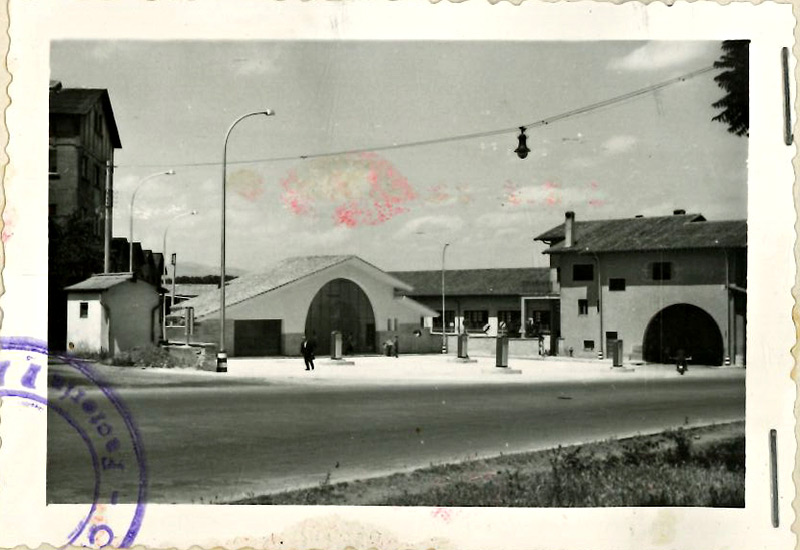

View of the service station in 1965 (advertising image on card oil change control).

The Promoter: Vicente Munárriz y Sanz de Arellano (1897-1981)

Vicente Munárriz had been involved in the motor world for years, when in 1938 he requested licence for a service station. At that time he owned a garage on San Ignacio Avenue, located in front of the Olimpia movie theater, where he represented several automobile and motorcycle brands. There he acted as a "gas-oil reseller agent with a privately owned pumping device inside the premises", mainly for consumption by the "Flecha Azul" coaches. This company, founded in 1929, in which he had a shareholding, was a pioneer in Navarre in the commercialization of tourist trips in luxury coaches with " toilettecabins". It offered excursions, among other destinations, to Barcelona, to its Universal exhibition , and to Rome, on the occasion of the Holy Year of 1933. Shortly after, it would operate the regular line from Pamplona to Zaragoza.

Munárriz was linked to Carlism and during the civil war he played a prominent role, with the rank of lieutenant of the Requeté, in the repressive structure of the board Central Carlista de Guerra de Navarra. This board, whose members included Víctor Eusa, had been created at the behest of General Mola to relegate the political organs of traditionalism and was in charge of managing the Carlist military units and implementing the repressive work of the Requeté. Fernando Mikelarena has collected testimonies on certain excesses with the life and property of some of the victims of the repressive arm of the board. Munárriz also participated in important events of the conflict, such as the capture of Bilbao, after which he took responsibility for the leadership of the services of research, or the process of merging traditionalists and Falangists into a single party, during which he intervened by pressuring the political representatives of Carlism to secure their support.

The opening of the gas station coincided with the beginning of a period of rationing of fuel consumption and restriction of the circulation of vehicles as a result of the difficulties in importing oil during the world war. This status may have caused Munárriz to lose interest in the business, as he sold it to Compañía Comercial Distribuidora S.A. (Discosa) in 1946. By then, his entrepreneurial nature had set his sights far from Pamplona: on the African continent. In 1943 he had moved to Spanish Guinea, accompanied by two of his brothers and several people from Pamplona, among them his friend and rally co-driver Pascual Lizarraga. According to Lizarraga's son, they stayed there for four years dedicated to the construction business, erecting some of the government buildings in the colony.

Munárriz's next destination would be Liberia, where Vicente Munárriz Industrial Corporation developed activities in the manufacturing (bricks and tiles, soap, palm oil) and construction sectors. The guidebooks of the time indicate that he also represented the maritime line that linked the peninsula and Fernando Poo with a stopover in Monrovia. He even proposed a city project for seven hundred families, with church and university, called "Tubmanville", in honor of the then president. test of the consideration achieved among the authorities of that country was his appointment in 1950 as consul of Liberia in Madrid, position that his descendants continue to perform today. He was also decorated as an officer of the Order of the Star of Africa. In 1963, the Spanish government awarded him the Encomienda al Mérito Civil, which was presented to him at the embassy in Monrovia. This episode highlights the close relations that Munárriz maintained with influential personalities from the upper echelons of the Franco regime, who must have been useful to him in his business ventures.

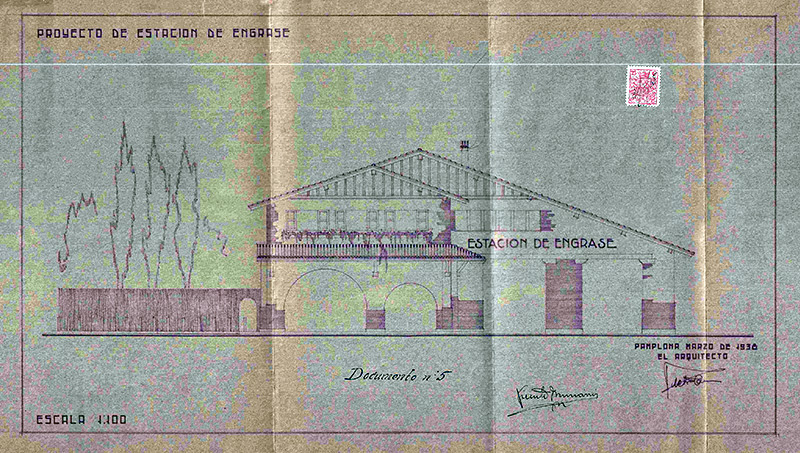

project by Víctor Eusa: elevation (file Contemporary of Navarra).

A gas station in the Basque regionalist style

The political networks of Carlism would be the point of contact between Vicente Munárriz and Víctor Eusa, an architect already consecrated in 1938 who had been able to successfully introduce his unique forms among the conservative Pamplona elite. Great buildings such as the Casa de Misericordia, the high school de Escolapios, the convent of Paúles, the Casino Eslava or the seminar had consolidated his predominance in the architectural panorama of the capital. That year he was interim municipal architect, following the political purge of Serapio Esparza, a post from which he promoted urban interventions such as the parks of average Luna and Taconera or the redesign of Portal Nuevo.

The image of the access to Pamplona from San Sebastian would be shaped by the work of Eusa, starting with the gas station, followed by the Portal Nuevo (1939, completed in 1950), the facade of the Recoletas towards the slope of the station (1932) and the halt with toilets or "umbrellas" of the Taconera (1938).

The service station occupied a plot of land of four robadas and average located in Trinitarios, next to the yeast factory of Eugui Hermanos y Muruzábal, acquired for 36,000 pesetas from sponsorship Ruiz de Latorre (January 28, 1938). The surface would be enlarged with a small plot of land owned by the Eceiza y Murillo Society (November 26, 1938). The location was unbeatable for cars and trucks, in plenary session of the Executive Council industrial district of the city, "between important factories of sugar, alcohol, chemical fertilizers, tanning, yeast, mechanical weaving, soaps, Northern railroad station and warehouses near it", and next to the road to San Sebastian, Vitoria and Bilbao. This exit lacked a service station, unlike those of Zaragoza and France, and the drivers only had two pumps located in Navas de Tolosa street and in Berriozar.

The request and subsequent concession of the licence by Campsa and Eusa's plans date from March 1938, in the middle of the civil war. Construction must have begun in September, at position de Huarte y Compañía, with a budget of 230,000 pesetas, being finished by June 1939, since on the 25th the contract for the supply and sale of gasoline was signed.

The complex had a staggered floor plan resulting from the intersection of two parts: on the one hand, the owner's house with the refueling area and, on the other, the garage building, which was behind and semi-hidden in its proportions. The first was organized in turn on two levels: the floor leave with the gas station and its outbuildings, and the second floor for housing. The gas station was resolved as a covered porch with four pumps, two on the exterior platform, next to the support columns of the facade, and two others next to the enclosure wall. In this way, the vehicles had two tracks for refueling, one completely sheltered from the weather and the other more open with only an eave for protection. On the upper floor was the Munárriz family home, which took advantage of the planimetry to extend its surface over the porch and the garage. This long shed had two entrances: the one on the right gave entrance to the room used for greasing; the one on the left led to a large area where there were spaces for parking vehicles, with a workshop and a storeroom at the back.

The main elevation is designed to emphasize the refueling area by means of large semicircular arches topped by an eave supported by brackets. On the other hand, the garage and the conference room greasing area are differentiated by their linteled entrances. On the second floor there are openings of different sizes, but with a uniform composition, which show the continuity of the living space. For its part, the gable end is resolved fragmentarily in skirts of unequal size that reflect the complex planimetry of the whole. The result is a facade in which Eusa deploys a harmonious combination of forms and volumes that come to highlight the different uses of the building.

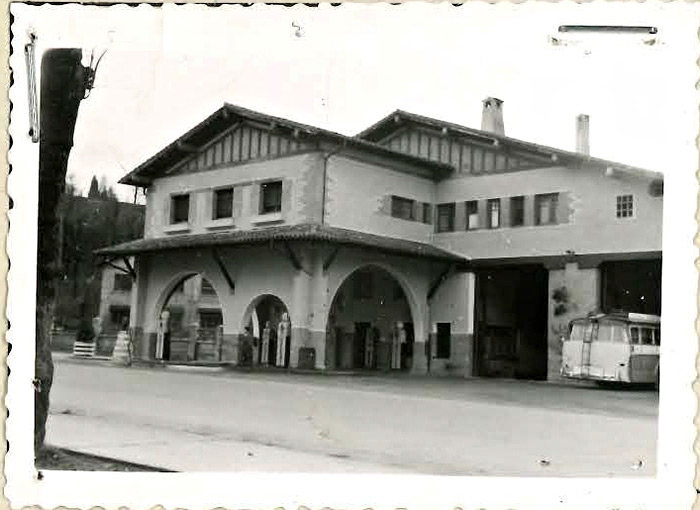

View of the service station in 1953 (file Contemporáneo de Navarra).

In a work that lacks the expressive force of his major projects, the hallmark is the original semicircular arches that emphasize the area refueling. It consists of two enormous access arches, enough to be used by trucks, plus two others on the platform, each of a scale. The dimensions of these openings allowed good illumination of the interior of the porch and the rooms on the floor leave. It was precisely in the 1930s that this arched subject became increasingly important in Eusa's architecture. He used it to shape wall openings: the Fuenterrabía settlement building (1933); covered accesses: the Mendía Parador in Alsasua (1935), the branch of the Caja de Ahorros de Navarra in Elizondo (1938); or porches in villas: villa Adriana (1934), here also with arches of different scales. The use of the semicircular arch will evolve towards a more classical and monumental conception in the access portico to the cemetery of Pamplona (1940) and will reach its greatest beauty and perfection in the atrium of the mausoleum of the Italians in Zaragoza (1940), composed of four large granite arches in the manner of severe and solid triumphal arches.

The other distinctive aspect of the facade is the use of the Basque regionalist style, a rather conservative approach in relation to other gas stations. Typical elements of this style can be observed, such as brick at corners and window frames, exposed timber framing with brick masonry and wooden javelins to support the eaves. The regionalist language presents a great sobriety, without stone or wooden balconies, which did animate Eusa's previous works. It should be remembered that under this traditional architectural garb, reinforced concrete and metal Structures were used. However, the plurality of materials, the tile of the eaves, the rendering of the wall and the jets themselves provided a certain chromatic play that broke the general austerity of the whole.

It is surprising that an architect who was well informed of the national and international scene through specialized magazines and who, as a car owner, was familiar with the most modern service stations, did not take the opportunity offered by this commission to experiment and give it a cosmopolitan air. Eusa avoided the rationalist and art deco languages whose combination was very common in gas stations and which he himself had mastered brilliantly. One can imagine the visual power of his project under these premises, which could have counted on a light and dynamic cover, a tower or a careful typography as the establishment's claims, as in the best-known examples of that time.

Paradoxically, Eusa resorted to popular tradition for an architectural typology given over to modernity. This circumstance may have been an imposition of the promoter, but also a meditated choice of the architect, who used these forms in his non-urban constructions, such as the small houses on the outskirts of Pamplona or the hotels and restaurants on the road. In addition, those years of his production are characterized precisely by works of clear regionalist inspiration, such as the colonies of Zudaire and Fuenterrabía (1933), villa Adriana (1934), parador Mendía (1935) or the Caja de Ahorros in Elizondo (1938). On the other hand, a very similar nearby gas station could have served as inspiration, like the one in Behobia (Luis Vallet, 1928), also composed of a gallery of arches under a Basque-inspired building. In any case, Eusa did not limit himself to a mere imitation of regionalist schemes, but added his own genuine touch with the original arcade of the refueling area.

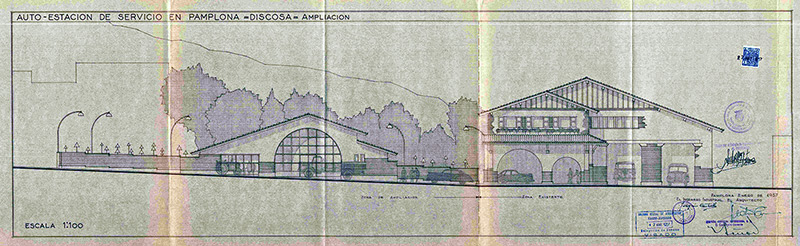

project enlargement by Víctor Eusa: elevation (file Contemporary of Navarra).

The 1957 extension

Compañía Comercial Distribuidora S.A. (Discosa), incorporated in 1945 in Barcelona, was a business dedicated to the operation of service stations. In 1946 it acquired Vicente Munárriz's station for 650,000 pesetas and also Jesús Díaz Martínez's station located on Avenida Zaragoza. However, the transfer of the business would not be authorized by Campsa until 1954. Shortly afterwards, the expansion of the facilities would be started, according to project by Víctor Eusa, whose goal was, on the one hand, to increase the capacity of the tanks from 40,000 to 120,000 liters and, on the other hand, to facilitate refueling by increasing the number of pumps from four to eight, issue . This was in response, respectively, to the growing demand for fuel and the considerable size of the heavy vehicles, which had difficulty maneuvering in the covered porch.

In the expansion, Eusa abandoned the original approach of a compact building where all the services were grouped together to separate the refueling area. In the esplanade next to the original building, three wide lanes were formed, separated by the paired pumps. The architect decided not to build a covering structure and this space was left exposed to the weather. Behind it, he erected a small pavilion for toilets, conference room waiting area and exhibition and sale of parts, with an elevation that matched the previous one.

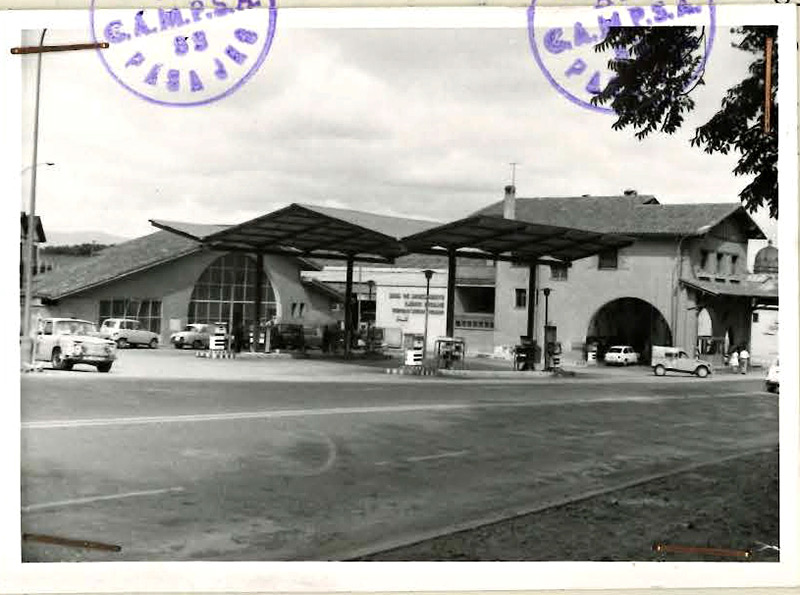

View of the service station in 1958 (file Contemporáneo de Navarra).

In fact, it repeats the outline arch and gable roof, which is not symmetrical, but in a cleaner design , stripped of regionalist ornamental references. The immense semicircular arch surrounds a large glazed surface in which a fine metalwork forms an abstract decoration based on squares, repeated in the horizontal opening that opens next to it. In this way, the three fundamental shapes are again combined in a subtle geometric play. The result can be considered a sophisticated interpretation of the first project and one of the most interesting works of Eusa's creative autumn.

In the 1950s, according to Muruzábal, the colorful paintings of the porch also materialized, showing the distance of Pamplona from other cities, symbolized by some distinctive element. Their author was Leocadio Muro (1897-1987), professor at the School of Arts and Crafts of Pamplona and specialized muralist, characterized by a sympathetic and attractive style. In fact, many people from Pamplona remember the gas station more for these decorative paintings than for its architecture.

Eusa would still be involved in two minor projects: a small building with an uralite roof for tire repair (1970) and the disuse of several tanks and the installation of new ones to increase storage capacity (1971). Both are a sample of the subject of orders he received in the years prior to his retirement. On the other hand, the roofing canopy was entrusted to an engineer (1969), who erected an unpretentious metal structure that was difficult to fit in with the other buildings in the complex.

View of the service station in 1969 (file Contemporáneo de Navarra).

The service station, which was one of the most complete in Pamplona, with cafeteria and car wash, would be demolished between 2012 and 2014 due to the conversion of Avenida de Guipúzcoa into a pedestrian zone. The business, owned by Cepsa since 1993, was moved to a nearby plot. Thus disappeared one of the most unique historical gas stations in Navarra, representative of the era of popularization of the automobile, where Eusa used a traditional Basque language to which it gave its own character through the original arches and the innovative re-reading of the subsequent extension.

SOURCES AND BIBLIOGRAPHY

file Contemporary of Navarra. Authorizations for service stations and pumps. 422255/1.

file Municipal of Pamplona. Construction licenses. 1938/2/101, 1938/3/143, 1957/4/87 y 1970/9/28.

Diario de Navarra.

LIZARRAGA LARRIÓN, L. J., El banco de los jardines. Recuerdos para la recapitulación de una vida, Pamplona, Sahats, 2015.

MIKELARENA PEÑA, F., Sin piedad. Limpieza política en Navarra, 1936: responsables, colaboradores y ejecutores, Arre, Pamiela, 2015.

MURUZÁBAL DEL SOLAR, J. M.ª, "Leocadio Muro Urriza". Pregón Magazine, Siglo XXI, 23 (2004).

RODRÍGUEZ ARIAS, A., The service station as a field of experimentation in Spanish avant-garde architecture (1927-1967).. thesis Doctoral dissertation. University of A Coruña, 2021.

TABUENCA GONZÁLEZ, F., The architecture of Víctor Eusa. thesis Doctoral dissertation. E.T.S. Architecture (UPM), 2016.