Hydroelectric power plants in the Bidasoa basin

Introduction

The innovations that made it possible to harness river water for the production of electricity had a wide repercussion in Navarre. In the last decade of the 19th century and the first two decades of the 20th century, the hydroelectric sector experienced formidable growth until it became the main industry in the province. Most of the direct current power stations were installed in the old flour mills to supply electricity for lighting in nearby villages. However, the development of alternating current, which allowed more energy to be transported over longer distances, favoured the construction of more powerful power stations, whose business was to supply Pamplona and, above all, Guipúzcoa, a highly industrialised territory with its hydraulic resources exploited to the maximum.

The most important basin in terms of hydroelectric production was the Bidasoa basin, an area with favourable conditions due to its abundant rainfall and steep slopes. internship In the 1930s, 30 % of the installed capacity in Navarre was located there, all of which was transferred to the market in Gipuzkoa. The installations of some of the main companies in the sector - such as Electra Puente Marín or Saltos del Bidasoa - were fed by the water of the Bidasoa and its tributaries.

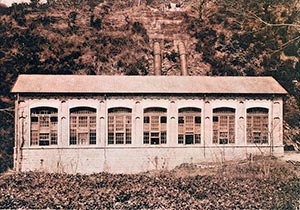

In hydroelectric complexes, the most representative heritage element is the power station or powerhouse, which houses the machinery that transforms the energy contained in the water into electrical energy. In many cases, this is industrial architecture that goes beyond the merely functional, as it is a display of creativity that turns the building into the image of the prosperity of the owning company. In its design an attitude of whimsical eclecticism can be perceived, with influences from the fashionable trends at the beginning of the 20th century: Basque-inspired Regionalism and Modernism. In contrast, from the late 1920s onwards, the aseptic, unadorned language advocated by Rationalism gradually took over.

Generally speaking, powerhouses usually have a rectangular floor plan, of greater or lesser length and width depending on the issue generation groups they house. The most common roof is metal, double-sloped and located at a certain height. The side walls have large windows that provide light and ventilation. The result is a spacious, open-plan and bright interior. At one end of the building are the transformer, metering and safety equipment, etc. and the outlet for the overhead high-voltage lines, which sometimes gives rise to a pavilion protruding from the building. The foundations are made of concrete to support the weight of the machinery and absorb the vibrations of its operation. The value of the turbines and the rest of the equipment inside the power stations must be underlined. They are centuries-old imported pieces, which at the time were at the cutting edge of technology and many are still in use today.

The projects for the hydroelectric dams were commissioned to a small number of engineers, who in some cases were assisted by architects partnership to design the powerhouses. One of the most prominent was Miguel Berazaluce Elcarte (1886-1954), who was involved in at least five of the power stations analysed in this pathway. The son of the first director of Diario de Navarra, he finished his programs of study at the School of Engineers in Madrid in 1908. employment From then on, his dense and little-known professional career began, in which, in addition to hydroelectric power stations, we can highlight the first time that reinforced cement was used in Navarre (1911), the start-up, together with his father-in-law, Julio Altadill, of the Electro-Chemistry San Miguel factory in Pastaola (1923) and the promotion of potash mining during the last years of his life.

But hydroelectric power plants are much more than just the architecture of the powerhouses. They are large engineering projects whose construction irreversibly transforms the existing landscape. The water, after being collected in a dam or reservoir, is channelled through a long pipeline to the load chamber, a regulating reservoir from which it falls through the penstock to the turbine in the powerhouse, whose rotary motion starts the electricity generation process. The height of the waterfall, that is, the difference between the point where the water is taken and the point where it is returned to the river once it has been turbined, determines the characteristics of one of the most spectacular elements of the project, the penstock, which can climb hundreds of metres in the middle of the mountain.

The transformation of the natural environment has been particularly intense in the Bidasoa basin, which can be recognised as an "electric" cultural landscape. This approach, which has had very little success to date, could contribute to the safeguarding of a heritage endangered by the termination of concessions and the removal of dams in order to recover the fish habitat. Furthermore, with their enhancement, the hydroelectric power stations could become another tourist attraction for the area. A first step in the dissemination and enhancement of this heritage has been the book coordinated by Susana Herreros Lopetegui, Centrales hidroeléctricas en Navarra (1898-2018), in which all the facilities known about have been catalogued and their historical and cultural dimension has been highlighted, which in the area of the Bidasoa reaches great relevance due to the high concentration of projects and the originality of their industrial architecture.

ALEGRÍA SUESCUN, D., "El molino harinero de Zubieta. Evolución histórica", in Notebooks of ethnology and ethnography of Navarren.º 82 (2007), pp. 5-15.

APEZTEGUÍA ELSO, M. and IRIGARAY SOTO, S., "El Ecomuseo del Molino de Zubieta (Navarra): experiencia pionera en la recuperación y musealización de una instalación preindustrial", in Museum: Magazine of the association Profesional de Museólogos de España (Professional Association of Museologists of Spain)No. 4 (1999), pp. 181-192.

BERAZALUCE ELCARTE, M., "La industria hidro-eléctrica en Navarra", in Rafael Guerra (ed.), Navarra. Ayer, hoy y mañana, Pamplona, Diputación Foral de Navarra, 1933.

HERREROS LOPETEGUI, S. (coord.), Centrales Hidroeléctricas en Navarra (1898-2018), Pamplona, Gobierno de Navarra, 2020.

Map of status based on El agua en Navarra, Pamplona, Caja de Ahorros de Navarra, 1991.