The Romanist sculptor Juan de Anchieta

By Pedro Luis Echeverría Goñi

|

|

MAIN ALTARPIECE OF THE PARISH CHURCH OF SANTA MARÍA DE CÁSEDA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

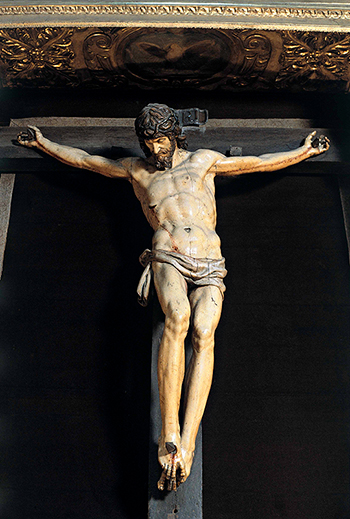

Santo Cristo del Miserere of Tafalla

This exceptional image of Anchieta has aroused over the centuries among the residents of the town of Cidacos and its region a devotion only comparable to that of the Andalusian Crucifixions, because, as his documentalist Cabezudo Astráin wrote, "it produces before those who contemplate it the purest emotion of faith and art". Perhaps we are before a donation of the sculptor himself or, more probably, of his widow Ana de Aguirre, to the church that keeps his masterpiece, the main altarpiece of Santa Maria, which he would not get to see finished. We will have to wait until the turn of the century to know the data that accredits its authorship, since in the 1600 contract between the chantre, deputy mayor and neighbors with the painter Juan de Landa to make a mixed altarpiece that would house it, it is said that "it is to put the Christ that is made by the hand of Ancheta" and "for the adornment of the Christ and his chapel", which was of board of trustees of the town. Its origin is in the popular brotherhood of the Vera Cruz, of which the regiment was patron, promoted from its origin by the Franciscans and that had, according to G. Silanes, penitential and penitential purposes. Silanes, penitential and processional and indulgencial purposes.

Its name comes precisely from the first Latin word, Miserere, which begins Psalm 50, which relates the visit of the prophet Nathan to David after his sin with Bathsheba. Previous recognition of the guilt, is exalted in this penitential psalm the supplication of the repentant sinner, asking for mercy to the Lord, in the prayer of the lauds of every Friday. In the atmosphere of the Counter-Reformation, it constitutes a whole propaganda of Christian repentance and of the sacrament of confession. In the attic, the patrons ordered Landa to paint a canvas of the Holy Burial which, through pretenebrist lighting effects, moves us before the dead Christ.

Although it does not surpass the Christ of the cathedral of Iruña, made for the first temple of Navarra, it is an exceptional work that adds to its obvious technical and stylistic values, the fact that it still has the contemporary incarnation applied by the painter Juan de Landa in 1600, which turns this God made dead man into the conqueror of sin. Its comparison with the one made for the Barbazana explains the maturity reached by our sculptor in the ten years between the execution of both. Although they present the same canonical outline of the Romanist crucifixions, derived from drawings by Michelangelo, such as the one in the British Museum, in this one from Tafalla we can clearly see his more serene face, as his head is not slumped and his hair is pulled back. We recognize perfectly that Byzantine subject of aquiline nose and short and forked beard that was already consolidated. Although he has expired, he is a dead man who lives. The work denotes a greater balance, without exaggeration in the torsions or in the curvature of the body. As García Gainza pointed out with great acuity, the greater classicism of this last image may be due to the contemplation in the monastery of El Escorial of the sculptures of Pompeo Leoni and Juan Bautista Monegro during the trip he made to this Royal Site in 1583.

The masterful anatomical treatment of the muscular planes presents us with the athletic body of a 33-year-old man in his prime which, due to its hyperrealism, demands more of a physiopathological than an art-historical study. In what fully coincides with the crucified of the cathedral is the representation of the hands half closed and contracted by the action of the nails on the metatarsus and metacarpus, and the right foot mounted on the left with the separation of the big toe in V. She is covered with a minimal purity cloth or horizontal strip of cloth knotted on her right hip, which exposes an Apollonian nude. The softness of this body, carved from a walnut trunk, was obtained when the sculpture was finished in white, but it was definitively covered with an epidermis thanks to the polished incarnation of the king of arms by Juan de Landa, which would have fully satisfied its author Juan de Anchieta. The painter's mastery can be appreciated even in the fine threads of blood and their course on the skin. With this complement, which still remains, was given to this image of devotion, the last life and expression.

CABEZUDO ASTRAIN, J., "Church of Santa María de Tafalla", Príncipe de Viana, 67-68 (1957), pp. 426-431.

CAMÓN AZNAR, J., El escultor Juan de Anchieta, San Sebastián, Diputación Foral de Guipúzcoa, 1943.

ECHEVERRÍA GOÑI, P. L. and VÉLEZ CHAURRI, J. J., "López de Gámiz and Anchieta compared. Las claves del Romanismo norteño", Príncipe de Viana, 185 (1988), pp. 477-534.

GARCÍA GAINZA, M.ª C., "El retablo de Añorbe y el arte de la Contrarreforma", in La recuperación de un patrimonio. El retablo mayor de Añorbe, Pamplona, Caja de Ahorros de Navarra, 1995, pp. 4-18.

GARCÍA GAINZA, M.ª C., Juan de Anchieta, sculptor of the Renaissance, Madrid, Fundación Arte Hispánico, 2008.

GARCÍA GAINZA, M.ª C., La escultura romanista en Navarra. Disciples and followers of Juan de Anchieta, 2nd ed., Pamplona, Government of Navarra, 1982.

GOYENECHE VENTURA, M.ª T., "La obra de Juan de Anchieta en la iglesia parroquial de Santa María de Cáseda (Navarra)", Príncipe de Viana, 185 (1988), pp. 535-562.

TARIFA CASTILLA, M.ª J., "Los modelos y figuras del escultor romanista Juan de Anchieta", in Fernández Gracia, R. (coord..), Pvlchrvm Scripta varia in honorem M.ª Concepción García Gainza, Pamplona, Gobierno de Navarra-Universidad de Navarra, 2011, pp. 782-790.

VASALLO TORANZO, L., Juan de Anchieta. Aprendiz y oficial de escultura en Castilla (1551-1571), Valladolid, Universidad de Valladolid, Secretariado de Publicaciones e exchange publishing house , 2012.