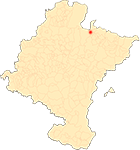

Roncesvalles

By Javier Martínez de Aguirre Aldaz

Chapel of the Holy Spirit

At the exit of the village on the road leading to Santiago is the chapel of the Holy Spirit, also known as the Silo de Carlomagno (Charlemagne's Silo) due to the ancient tradition that it was supposedly built by the emperor himself to bury the Franks who died in the battle of Roncesvalles. Moved by legend, for centuries pilgrims, especially French pilgrims, have honoured the reportof the defeated here and have even taken bones from the ossuary as a pious reminder of their ancestors. It is the oldest of the buildings that currently make up the hospital complex. A date between 1170 and 1210 seems plausible.

The main purpose of the chapel was to serve as a burial place and chapelwhere to pray for the deceased, both travellers and local residents.

The 13th century poem contained in the codex La Preciosa describes its peculiar configuration: "This monument is square on all sides; the highest part is rounded (or dome-shaped) and at its top there is a cross, a sign of defeat for the prince of darkness". It is constituted by a masonry well of 8.80 x .60 meters of side and proven depth of 9 meters. It is covered with a half barrel vault. Above it rises the chapel itself, formed by the intertwining of two powerful pointed arches of rectangular section. It has in its center an altar, as the old sources also counted. Around this nucleus is organized a closing of semicircular arches on pillars with molding marking the impost line.

Its use as an ossuary connects with the tradition of centralised spaces with funerary functions, existing since early Christian times and heirs to much older works where a link was also established between the central floor and the world of death. The well and its surroundings provided a burial place that could always be reached, even in the harshest weather conditions, conveniently sectionfrom the collegiate church but not so far as to be difficult to access.

Dectot, X., "Yacente de Sancho VII el Fuerte", in Bango Torviso, I.G. (dir. cient.), Sancho el Mayor y sus herederos. El linaje que europeizó los reinos hispanos, Pamplona, 2006, pp. 371-373.

Fernández-Ladreda, C., Imaginería medieval mariana en Navarra, Pamplona, 1989.

Fernández-Ladreda, C. (Dir.), Martínez Álava, C., Martínez de Aguirre, J. and Lacarra Ducay, M.C., El arte gótico en Navarra, Pamplona, 2015.

Fuentes y Ponte, J., report histórica y descriptiva del santuario de Nuestra Señora de Roncesvalles, Lérida, 1880.

García Gainza, M.C., Orbe Sivatte, M. and Domeño Martínez de Morentin, A., Catalog Monumental de Navarra IV**. Merindad de Sangüesa, Pamplona, 1992.

Ibarra, J., History of Roncesvalles. Art. History. Legend, Pamplona, 1936.

Lambert, E. Roncevaux", Bulletin Hispanique, XXXVII (1935), pp. 417-436.

Martínez de Aguirre, J. (coord.), Enciclopedia del Románico en Navarra, Aguilar de Campoo, 2008, vol. III, pp. 1216-1224.

Martínez de Aguirre, J., Gil Cornet, L. and Orbe Sivatte, M., Roncesvalles. Hospital and sanctuary on the Camino de Santiago, Pamplona, 2012.

Miranda García, F. and Ramírez Vaquero, E., Roncesvalles, Pamplona, 1999.

Peris, A., "El Ritmo de Roncesvalles: estudio y edición", Cuadernos de Filología Clásica. Latin Studies, 11 (1996), pp. 171-209.

Pons Sorolla, F., "project de obras de restauración en la capilla del Sancti Spiritus de la Real Colegiata de Roncesvalles (Navarra)", Príncipe de Viana, XXXIX (1978), pp. 59-77.

Soria i Puig, A., The Road to Santiago. II. Stations and signs, Madrid, 1992.

Torres Balbás, L. La iglesia de la hospedería de Roncesvalles", Príncipe de Viana, VI (1945), pp. 371-403.

Thuile, J., L'Orfèvrerie en Languedoc du XIIe au XVIIIe siècle. Généralité de Montpellier, Montpellier, 1966.