LOS ARCOS AND ITS DISTRICT: THREE CENTURIES BETWEEN TWO KINGDOMS (1463-1753)

14 September 2016

Tasting and tasting: the arts at the service of the senses in the parish of Los Arcos

D. Ricardo Fernández Gracia. University of Navarra

Human beings are a mixture of feelings, reasoning, beliefs, circumstances and lived experiences. The latter, together with feelings, played a major role in the transmission of culture in times when images and sounds were scarce.

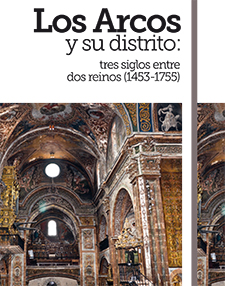

The interior of the parish church of Los Arcos is today one of the most outstanding examples of the decorative, rhetorical, theatrical and sensual baroque in Navarre during the Baroque centuries, in the context of a culture that overvalued the senses as being much more indelible than the intellect and therefore able to enervate and captivate the individual, marking behaviors. The location of the town, then belonging to Castile, between localities and artistic centers of La Rioja and Navarre, with the proximity of Viana, Estella and Calahorra, favored the flow of artists from different origins. In the same sense, its belonging to the bishopric of Pamplona and its proximity to localities of the great miter of Calagurritana should be noted, which also acted as an incentive for the arrival of artistic influences and exchange of masters and workshops.

The parish church of Santa María de Los Arcos is one of the most significant examples of decorative baroque in Navarre.

The sense of sight was extolled by Leonardo as follows: "Painting is a poetry that can be seen without hearing it; and poetry is a painting that can be heard and not seen; so these two poetries, or, if you prefer, two paintings, use two different senses to reach our intelligence. For if one and the other are paintings, they will pass to the common sense through the nobler sense, which is the eye; and if one and the other are poetry, they will have to pass through the less noble sense, that is, the ear." St. Thomas wrote: pulchra sunt quae visa placent (beautiful are the things that please the sight) and affirmed that beautiful are those things whose perception in their very contemplation pleases: pulchrum est id cuius ipsa apprehensio placet, which is in relation to the first, since sight, as the most perfect sense, replaces the language of the rest of the senses.

Orozco Díaz pointed out the progressive theatricalization of the church from the 17th century onwards in its psycho-sociological aspect, unleashed as a consequence of the Tridentine rules and regulations and analyzed as a phenomenon concomitant with the theatricalization of life. The church, with its pulpits, which represent an "overflow of the scene", the tribunes, organs and altarpieces, resembled a theater. The same author emphasizes that the temple "is conceived with a sense parallel to the scene to fulfill, in the divine, the social function that the altarpiece performs in the mundane", making clear the correspondence between the rhetorical artifices of oratory and the grandiloquent forms of the altarpieces that sought to concentrate the attention of the believer and stimulate the senses, transferring it from the material to the spiritual.

The unity of altarpieces, pulpits, plasterwork, wood carvings, painting, gold and colors of the interior of the parish of Los Arcos, wrapped in the rich liturgical ceremonial and polyphony, becomes a spectacle for all the senses, provoking the individual sensorially, moving and enervating him, always with the aim of moving and convincing through the senses, much more vulnerable than the intellect.

Parish of Los Arcos

Main altarpiece

The interior of the complex was baroque in crescendo from the middle of the 17th century onwards, from the construction of the main altarpiece to the building of the organ in the second half of the following century. The best artists were sought after by those in charge of the parish church, both for its reconstruction between 1699-1705, as well as for all subject commissions. His board of trustees was exposed to several lawsuits before the ecclesiastical authority for the right to contract artistic works, without going through higher instances. The best retablist of the Estellan workshop, Juan Ángel Nagusia, left the best of his knowledge and understanding in the altarpieces of San Gregorio (1710), collaterals of the Immaculate and San Juan Bautista (1718), great tabernacle-expositor (1736) and of San Francisco Javier (1741) in a chronology that covers a large part of his artistic life. Sculptors, gilders from here and there left the temple in the central decades of the century as a singular and rhetorical ensemble, but there was still something more. In the middle of the development period of Baroque decorativism, the parish received the most spectacular program for its richness, turning the temple into a true caelum in terris, as Pass for Baroque rhetoric. The commissioner was José Bravo, a painter from Burgos and master "major of the archbishopric of the said city and of the bishopric of Calahorra and La Calzada". The project was carried out between 1742 and 1745 and was expensive, amounting to 7,868 ducats of old silver. The artists who intervened judged that with all that decorative program with gold, silver and colors they were able to "give much sainete and sense of carving and architecture". Don Francisco Magallón y Beaumont played a fundamental role in all that project , who quotation in diligences to groups such as San Fermín de Pamplona and Santa Ana de Tudela, the church of high school of the Jesuits -probably referring to that of Tudela- and the chapel that was being built at that time in the collegiate church of Tudela, which we have to identify with that of the Holy Spirit. Among the words that are repeated over and over again, we find the concept of "beautifying" the temple with the rich iconographic program, meaning that they wanted to make something that would recreate and be pleasing to the eye and pleasing to the senses, while at the same time being proportionate and endowed with grace. The same document also argues and insists on two very Enlightenment concepts: "perdurability" in allusion to what lasts long and is forever, and "utility" making reference letter to everything that could be used, in this case, for divine worship and the delight of sight, as the main one of the senses. Among the chapters for the decoration and baroque of the temple of 1742, we highlight for its importance and exceptionality the one that deals with the decoration of the walls of the Wayside Cross and presbytery, where we read: "Iten that in all the whites of the cornice in low that there is in the main chapel and Wayside Cross to the pulpits, some hangings that seem to be of gold, in this form have to be pretended: The lines are to be made with the divisions that correspond to the width of the silk, and in the center that there is from one sash to another, a corresponding cloth and ornament is to be made, in the best imitation and taste of the art. And it is warned that the said hanging is to be made on boards, as well as that it is to be burnished silver minus the fields of said labors, which will be made of sapphire for its greater brilliance and beauty. Iten that the said silver of the hanging and all the rest that there would be, as it is referred, must be corlear with patent leather verniz, made with such property that belies the same gold, without being able to distinguish whether it is gold or silver, because the said verniz is more permanent than fine gold".

The interior of the church was gradually baroque from the middle of the 17th century.

Juan Ángel Nagusia was commissioned to build the collateral altarpieces in 1718.

The decorative program contracted in 1742 included painting the main chapel and

in the main chapel and in the Wayside Cross fake hangings

In the decorative program carried out between 1742 and 1745, Francisco Magallón y Beaumont

Francisco Magallón y Beaumont played a fundamental role in the decorative program

Prototipo de un templo barroco

Tras tratar de los aspectos generales y conceptuales, hay que hacer dimensionar y contextualizar el recinto del templo parroquial de Los Arcos desde cinco puntos de vista: 1. La piel de la arquitectura; 2. El poder de la palabra; 3. Per visibilia ad invisibilia: las imágenes; 4. Aparente infinito y 5. Música.

Respecto al primer aspecto, la profesora Blasco Esquivias recuerda en su Introducción al Barroco, que la Iglesia justificó el boato ornamental de los templos y el esplendor de sus ceremonias en la necesidad de honrar la presencia real de Cristo y fomentar la devoción de los fieles suspendiendo sus facultades racionales y estimulando sus sentidos, predispuestos ya por el ambiente colectivo y la formalidad de la liturgia, la riqueza de los ornamentos, la iluminación calculada del espacio, los vapores del incienso, la oratoria de los sermones y la música, que inducían a la enajenación o excitación espiritual. Yeserías, pinturas murales, retablos y cortinajes ficticios hacen de su interior el mejor y consumado ejemplo de los templos navarros del momento.

Las imágenes fueron extraordinariamente eficaces en momentos de escasez de las mismas, en que el tiempo para su contemplación era abundante, por lo que quien las miraba podía extraer distintas sensaciones y valoraciones. En definitiva y como ha escrito magistralmente David Freedberg, comparando tiempos pasados con los presentes, ya no tenemos el “ocio suficiente para contemplar las imágenes que están ante nuestra vista, pero otrora la gente sí las miraba; y hacían de la contemplación algo útil, terapéutico, que elevaba su espíritu, les brindaba consuelo y les inspiraba miedo. Todo con el fin de alcanzar un estado de empatía”.

Respecto al poder de la palabra y a la luz de los tornavoces de los púlpitos que dominan la nave, recordamos la relación y unidad de palabra e imagen, del lápiz y el pincel o la gubia. Los recursos retóricos y teatrales en los sermones estuvieron en sintonía con las imágenes. Estos últimos eran actos muy frecuentados y los predicadores cuidaron mucho de cuanto decían en el púlpito, preparando panegíricos ad hoc, según el auditorio, con el correspondiente ornatus repleto de la retórica imperante y siempre con el triple contenido de enseñar, deleitar y mover conductas. Al predicador se le exigía oración y estudio, así como excitar al fervor, haciendo gala de ciencia, elocuencia e ingenio. Todo ello en aras a conseguir los tres citados fines de la oratoria sagrada que no eran otros que el movere, o marcar conductas, no sólo deleitando y enseñando, sino moviendo los afectos en los corazones.

Los afectos eran diana fija en las palabras y los argumentos de los predicadores del momento. Recordemos lo que escribe el Padre Granada, tan leído por los panegiristas: “Pues entre los afectos de devoción, unos corazones hay inclinados a compasión, otros a amor, otros a temor, otros a esperanza, otros a dolor de los pecados, otros a admiración de las obras divinas, otros a menosprecio del mundo, otros al aborrecimiento del pecado, y otros a otras maneras de afectos semejantes. Pues ¿para cuál de éstos no e hallarán motivos y despertadores en la vida y muerte del Salvador? ¿A quién faltarán lágrimas de devoción en los misterios de su niñez, y de compasión en los de su muerte, y de amor en los beneficios de su vida santísima? ¿Quién no se maravillará del abismo de tan profunda humildad y caridad como resplandece en todas las obras…”.

Todas las imágenes que pueblan los retablos, verdaderas escenografías áureas constituyen un verdadero ejemplo de lo que podemos denominar per visibilia ad invisibilia. El profesor Rodríguez G. de Ceballos afirma que los retablos de las iglesias servían maravillosamente para la función de aprender, contemplando sus iconografías, mientras se escuchaba el sermón, puesto que el predicador casi podía ir señalando con el dedo desde el púlpito las escenas de pintura o relieve para apoyar sus palabras, “a la manera del coplero ciego señalaba con una varita en la calle los dibujos desplegados ante los espectadores que escuchaban embobados su relato”. Con las imágenes se aprende, se descubre, se comprende, se entiende, se conoce y se reconoce y a través de ellas se puede generar un estado de empatía. Al respecto, recordaba Alberti en su tratado De Pictura (1487): “Una “historia” conmoverá los ánimos de los espectadores cuando los hombres pintados allí expresen sus emociones con claridad. Y, como la naturaleza hace que no pueda haber nada más deseoso que las cosas semejantes a sí, lloramos con los que lloran, reímos con los que ríen y nos dolemos con los que se duelen”.

Por lo que se refiere a la presencia de alegorías y otros símbolos de difícil interpretación, hay que recordar la diversificación de niveles culturales (85% analfabetos) y que algunas parcelas de significación artística y literaria se reservaron para minorías cultas, en un fenómeno que se ha denominado como de “discriminación semántica”. Existen, por tanto, distintos niveles de lectura, para contentar a masas y minorías: en el teatro existen citas y referencias eruditas inaccesibles a la comprensión de los no letrados, que junto a una primera trama argumental inmediata, narrativa y “lineal”, convivan sub-tramas y elementos simbólicos que actúan como complemento retórico de ésta y sólo pueden ser entendidos por personas doctas. Algo parecido ocurre en muchas composiciones artísticas. Además, existían distintos gustos: por una parte el público mayoritario que gusta de todo aquello que impresiona vivamente a sus sentidos y una minoría cultivada que, tras las apariencias busca proporción, correspondencia o decoro (adecuación entre significante y significado) y desconfía de cuanto aprueba la mayoría. Además de lo decorativo puramente, hay que señalar el interior de Los Arcos como uno de los escasos que ofrece un conjunto de alegorías riquísimo: las tres virtudes teologales y otras como la liberalidad -esparciendo objetos de valor-, la soberbia -con las plumas del pavo real-, y la envidia -comiéndose su propio corazón-. Por último, no falta el testimonio de quien era el alma de toda aquella barroquización con las pinturas ilusionistas: don Francisco de Magallón y Beaumont, V marqués de San Adrián, alcalde de Los Arcos en 1742, hombre ilustrado convencido y con amplia cultura. Interesado en el negocio del vino por las repercusiones económicas tan fuertes para la economía de la villa, defendió con sólidos argumentos ante las Cortes de Navarra que no había ninguna necesidad de descepar el término comunal de Los Arcos para arreglar los problemas surgidos con la exportación de vino, como si fuera un impedimento para la reintegración de la villa a Navarra. Cuatro pinturas alegóricas ligadas a la abundancia –joven con cesto de uvas sobre la cabeza-, el progreso de las artes –Apolo asociado con Horus-, la fama y la memoria se sitúan en los lunetos del crucero y vienen a ser una condensación de su pensamiento acerca del papel del viñedo en la economía de la localidad paralelo desarrollo de la cultura y las artes, como verdaderos de un hombre del siglo de las Luces.

The organ case was made by Diego de Camporredondo

The culmination of that festive space for the senses was the construction of the organ, whose case was awarded to Diego de Camporredondo, thanks to the mediation of his fellow countryman, the Bishop of Pamplona, Gaspar de Miranda y Argaiz, in 1759. The gilding of the box was done by Santiago Zuazo and the musical instrument was executed by Lucas de Tarazona from Lerin. In the bishop's recommendation in favor of the sculptor we read: "I highly commend the idea of promote the greater honor and splendor of your church with the organ and sacristy drawers to be made by the good hand of Camporredondo, that there is no other of more skill, security and satisfaction". As in other eighteenth-century examples, we are faced with a baroque piece of furniture, with a true scenography that occupies the back of the wall to which it is attached, made with formal complexity in plan and elevations with dynamism, ostentation and sumptuousness, with a fusion of the arts (architecture, sculpture and painting) that lends itself to the spectacular. In addition, the fact that it is covered in gold and color gives it great richness, while its decoration is based on symbols of abundance, triumph and glory, housing celestial characters playing percussion and string instruments. All this, together with the rhetoric of the preacher and the liturgical offices, seeks to generate an authentic caelum in terris, a miraculous and hallucinating space, typical of the Baroque, an art that wants to captivate through the senses, much more vulnerable than the intellect. As is well known, the sounds of the organ, especially in the Baroque period, became part of the elements of power within the temple, while they were also heard, as a metaphor for the angelic hierarchies. In the midst of the Baroque culture, so intimately allied with the senses, the voices and sounds of the organ constituted one of the most sensual means for the fascination of those who attended the ceremonies inside the temple. In 1636 Marin Mersenne had written: "[The Church] makes special use of the organ to capture the hearts of the faithful and transport them to the choir of angels".

PROGRAM

Wednesday, 14th September

Between Navarre and Castile (1463-1753)

D. Roman Felones Morrás. Lecturer in History of Art at classroom de la Experiencia. Public University of Navarra

Tasting and savouring: the arts at the service of the senses in the parish church of Los Arcos

D. Ricardo Fernández Gracia. University of Navarra

Thursday, 15th September

Another jewel of the Renaissance in Navarre: the altarpiece of San Andres de El Busto

D. Pedro Luis Echeverría Goñi. University of the Basque Country

Stone and stonework at the service of the Church and the nobility in Sansol

Ms. Pilar Andueza Unanua. University of La Rioja

Friday, 16th September

Armañanzas: in the footsteps of its church, altarpieces and emblazoned houses

José Javier Azanza López. University of Navarra

The artistic heritage of Torres del Río: much more than the Santo Sepulcro (Holy Sepulchre)

María Josefa Tarifa Castilla. University of Zaragoza

Saturday, 17th September

visit Guided tour to Torres del Río, Armañanzas, Sansol, El Busto and Los Arcos.