THE BAROQUE IN NAVARRA. THE PLEASURE OF FEELING AND THE JOY OF CELEBRATING

September 16, 2015

"Brick and ashlar prayer". Religious architecture in the Navarrese Baroque

Mr. José Javier Azanza López. Chair of Navarrese Heritage and Art.

A session dedicated to religious baroque architecture in Navarre can be approached from different perspectives: typologies, construction process, promotion and patronage, professional aspects and artistic culture of the masters, and even its patrimonial revaluation in recent decades thanks to projects such as the Catalog Monumental de Navarra. But we are going to stop on this occasion in the mechanisms that transform a stone or brick building into a space of persuasive purpose, aimed at moving the faithful to prayer.

The location is one of these resources. As Rudolf Wittkower means, "the Baroque was fond of sanctuaries set on high which, as visible symbols, dominated the landscape and suggested the immensity of nature controlled by men in the service of God". These words can be applied to several hermitages and sanctuaries in Navarre, such as the Yugo de Arguedas, Romero de Cascante or San Gregorio Ostiense de Sorlada; the latter, elevated on the Peñalba hill from which it dominates a very wide panoramic view, rivals the forms of the relief and acts as a spiritual beacon over the surrounding lands, located on the border between Navarre, Alava and La Rioja.

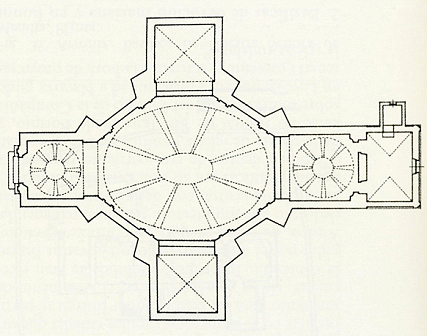

Most of the buildings of the Navarrese Baroque adopt a Latin cross plan, an arrangement favored for reasons of an architectural, liturgical and also symbolic nature, in that it represents "that wood on which our eternal salvation hung", according to Palladio(The Four Books of Architecture, 1570), an idea corroborated by Friar Lorenzo de San Nicolás(Art and Use of Architecture, 1633). As early as 1608 and at purpose of the parish of San Juan Bautista de Arizkun, the ecclesiastical overseer Francisco Palear Fratín, well versed in the artistic theory of his time, recommended the Latin cross with protruding Wayside Cross to the detriment of the single nave church because "that which does not have collaterals does not look like a church". However, there are exceptions that also obey a marked symbolism, as can be seen in the basilica of sponsorship de Milagro, designed by Pedro de Aguirre in 1699, which sample elliptical plan inscribed in an irregular octagon to which four chapels open on its main fronts, combining centralized space and outline cruciform. Possibly Pedro de Aguirre was aware of the ideas of Federico Zuccaro, who attributes to the oval plan a clear Marian symbolism; based on the existence of a "Marian-morphic" architecture for the elliptical spaces of devotion to the Virgin, a theory defended by authors such as Marcelo Fagiolo and Alfonso Rodríguez G. de Ceballos, the Miraculous Basilica places Navarre's Baroque architecture on a par with the most avant-garde centers of the peninsula.

Plan of the Basilica of Our Lady of Milagro sponsorship

Pedro de Aguirre, 1699

Inside, light and decoration are key elements in the persuasive purpose of Baroque architecture. In the culture of the Baroque, light is an element endowed with a profound meaning, since it is conceived as a way of praising Christ or the Virgin, whom the sermons of the time identify with light; and, in turn, it creates surprising contrasts of light that give rise to spaces charged with intense symbolism. An aspect related to light is the mirror, which can be considered an instrument of the baroque world, since it multiplies architectural and decorative forms, creates new perspectives and spatial effects, increases luminosity and transmits a sensation of unreality; it is also the bearer of a symbolism, since it alludes to one of the emblems of the Marian litany. The mirror finds its ideal setting in the sacristies, as we can see in the cathedral of Pamplona and in the parishes of San Cernin de Pamplona and Santa María de Viana.

The decoration leads us to a first discussion, which poses a dilemma almost in contemporary terms of figuration and abstraction: which subject of decoration moves prayer with greater force: the geometric, characteristic of the conventual architecture of the first two thirds of the 17th century, or the naturalistic, which is developed with profusion in the rest of typologies from the last third of the century? The latter forms an authentic "mask of architecture" (Hubert Damish, 1960) or "skin of architecture" (Alfredo Morales, 2010) that must be understood as an essential ingredient for a true understanding of the building. Not only artistic, but also sociological and religious reasons seem to justify such an aesthetic choice.

As Concepción García Gainza and Jesús Rivas Carmona have emphasized, the plasterwork of the Navarrese Baroque gives rise to ensembles that deserve to be included among the most representative of the Hispanic Baroque. The area tudelana is the area par excellence of the great decorative programs of the time, although we cannot ignore other examples of Pamplona and Tierra Estella in which the ornamentation transforms the interiors into authentic "liturgical theaters", creating in the faithful a sense of surprise that stimulates their devotion and brings them closer through the sensory to the great mysteries of the faith. Authentic "theaters to the divine" are, for example, the parishes of San Miguel de Corella, in which St. Michael and his archangelic hosts abduct the devil, who plunges into the abyss in a pronounced foreshortening that unites the earthly and heavenly planes; and Santa María de Los Arcos, where the architectural Structures are masked by a profuse decoration of plasterwork and paintings that, together with the set of altarpieces, make up one of the most surprising interiors of the Navarrese Baroque.

Vaults of the parish church of San Miguel de Corella

Interior of the parish church of Santa María de Los Arcos.

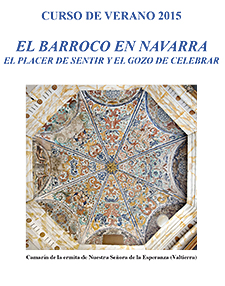

Special attention deserves within the ornamental chapter the so-called "architectures of persuasive purpose"; as Rupert Martin affirms, the stage-spaces, such as dressing rooms, tabernacles, reliquaries, chapels and transparencies, constitute "dazzling spectacles calculated to exalt the religious passions of the faithful to new heights of fervor and enthusiasm". A multitude of examples could be cited in this section , among which the chapels of Santa Ana and the Holy Spirit in the cathedral of Tudela stand out, as well as the dressing rooms, a typology studied by Ricardo Fernández Gracia in which light and decoration create a magical, almost supraterrestrial space, like a "small chest of wonders" in which the sacred image is kept. This is certified, among others, by the camarines of the Purísima (Cintruénigo), Yugo (Arguedas), Esperanza (Valtierra), Soto (Caparroso), Romero (Cascante) and San Gregorio Ostiense (Sorlada).

PROGRAM

Tuesday, 15th September

The Baroque, an invention of the 20th century?

Javier Portús Pérez. Prado National Museum

Does the Baroque exist in Navarre?

D. Ricardo Fernández Gracia. Chair of Heritage and Art of Navarre

Wednesday, 16th September

"Plegaria de ladrillo y sillar" (Brick and ashlar prayer). Religious architecture in the Navarrese Baroque

Mr. José Javier Azanza López. Chair of Navarrese Heritage and Art

The construction of an image of power: town planning, houses and palaces.

Ms. Pilar Andueza Unanua. Chair of Navarrese Heritage and Art

Thursday, 17th September

Of chisel, hammer and paintbrush. The visual arts at the service of the Church and power

D. Ricardo Fernández Gracia. Chair of Navarrese Art and Heritage.

Jewellery and silver. Adornment and function

Mª Concepción García Gainza. Chair of Heritage and Art in Navarre

presentation of the book Alonso Cano and the Lekaroz Crucifixion

Mª Concepción García Gainza. Chair de Patrimonio y Arte navarro