THE BAROQUE IN NAVARRA. THE PLEASURE OF FEELING AND THE JOY OF CELEBRATING

September 17, 2015

Jewelry and silver. Adornment and function

Ms. Concepción García Gainza. Chair of Navarrese Heritage and Art.

Navarrese silverware of the 17th and 18th centuries maintained, even more than in the Renaissance, the great activity of the family silversmiths' workshops that worked ostentatious pieces with moving profiles ornamented in the Baroque taste and also plain pieces generally destined for religious worship. On the other hand, the jewelry sample was of great brilliance both in the design and in the realization, judging by the preserved jewels. In recent years, Baroque silverware has become well known to us thanks to the cataloguing of the works produced in their entirety, which include hundreds of pieces, most of which are of a religious nature. On the other hand, the existence of numerous documents including the Ordinances of the guild and brotherhood of silversmiths, dated 1743, with additions in 1788, allow us to know everything about the organization of the guild of San Eloy and its operation, as well as the marking of the pieces. accredited specialization Special mention should be made of the Libro de Exámenes de los plateros de Pamplona (1691-1832), one of the few books of this subject preserved in Spain, which constitutes an invaluable source for the knowledge of the silversmiths who carried out their activity in Navarre in the centuries of the Baroque, as well as an extraordinarily rich material from the artistic, typological and documentary point of view. All of which has allowed us to approach the study of the period as a whole.

The silver marks

The employment of silver and gold forced to keep the law stipulated by the ordinances to avoid the fraud of precious metals, which made it mandatory to mark the pieces, rules and regulations that was already established since the Privilege of the Union (1423) promulgated by Charles III, and maintained during the sixteenth century. In Pamplona, the pieces traditionally bear two marks, the author's mark or "maker's mark" and the city's mark, which was stamped when it was verified that the law was correct, leaving the mark of the engraving as a trace. The double mark was maintained in the centuries of the Baroque in order to control the silver in the pieces already worked. The marks of the maker or author were mostly collected in the cataloging of the Catalog Monumental de Navarra but later they have been clarified and expanded with the comparison of the marks and the documentation. The mark of the city of Pamplona corresponds to a double crowned PP that alludes to its status as a kingdom.

Jewelry

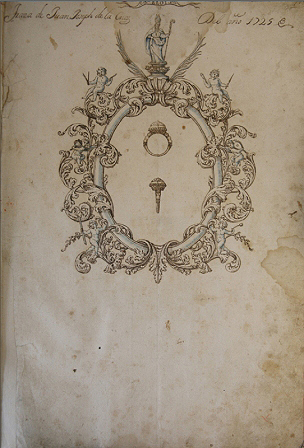

In contrast to the lack of knowledge about Navarre's Renaissance jewelry, the chapter on Baroque jewelry is of exceptional importance and can be illustrated with the drawings of jewelry from the Book of Examinations and the names of the most outstanding jewelers in Pamplona. The fourteen drawings of jewelry dated from 1700 to 1788 are a good representation of eighteenth-century jewelry, the main types of which show that they are up to date with the new fashions and designs based on French models. The preservation to the present day of a collection of locally produced Baroque jewelry kept in the jewel box of the cathedral of Pamplona is a brilliant illustration of this chapter. The goldsmiths will make their examination by drawing a jewel from the list of nine jewels listed in the Ordinances of 1743: alamar de guías, lazada de guías, piocha, joyel de guías, puño de bastón, sortija de oro, aderezo de cruz, par de broches para manillas o pulseras y sortija de memorias, an enumeration that is very useful on the typologies and terminologies in use at that time.

Ring. Drawing nº 31, made by Juan José de la Cruz in 1725.

Book of Examinations of the Brotherhood of Silversmiths of Pamplona.

file Municipal of Pamplona

It is precisely the ring that is the most frequently repeated jewel in the Book of Examinations. In 1725, Juan José de la Cruz, who became the most important jeweler in Pamplona, took his exams with a single cabochon ring. His most dazzling work is the crowns of gold, diamonds and emeralds of the Virgen del Sagrario, which were commissioned by the cathedral chapter of Pamplona, paid for with donations from devotees. Given the quality of this silversmith and the fact that he worked for the chapter, some of the exceptional jewels that are kept in the cathedral jewelry box are attributed to him, such as some of the four bibs, the ribbon and the scepter of the Virgin. The dungarees is a jewel to be worn at the neckline of the ladies' dresses. It is of horizontal deployment and complicated symmetrical structure with respect to a center in which stones are set and from it hang pendants, tremblers or cross.

Crown of Our Lady of the Tabernacle

Juan José de la Cruz, 1936

Pamplona Cathedral

Civil and religious silverware

Little has been preserved of civil silverware in comparison with religious silverware, which is widely represented and used to this day in churches as pieces of worship. Both were destined to a different clientele, formed in the case of civil silverware by the wealthy families that especially in the 18th century demanded pieces for domestic use, pieces of tableware, which illustrate the economic welfare and a certain concept of luxury. On the other hand, religious silverware was demanded by the numerous parishes, convents and by the cathedrals themselves, where they have been preserved in large quantities issue.

The scarcity of civil silver is compensated for by the Libro de Exámenes (Book of Examinations), which illustrates us more extensively with its drawings and typologies. The azafate or tray is the piece that has more representations issue , nineteen, ranging from 1694 to 1807 in which we can follow an evolution from late Baroque, Rococo to Neoclassicism and the introduction of French fashion. Other typologies are also represented, such as the pitcher, the workshop consisting of salt, pepper and toothpick shakers, wipers, basins or barber's basins, salvers, salvillas, braserillos or chofetas, mancerinas, coffee pots and cutlery.

Azafate. José Ochoa, 1780-1790

Museum of Navarra

The holy water fonts are of a devotional and domestic nature and are very ornamented pieces, especially the baroque ones.

The religious silverware responds to a traditional typology demanded by its function in the cult. A very high number of pieces have been preserved, issue , in spite of later disappearances. Among the most demanded pieces is the chalice, although the richest are the vestments of the patron saints or the altar frontals where the baroque exuberance is concentrated. Among the altar platforms are those of San Fermín (1735), by Antonio Ripando, and those of the Virgen del Camino (1702) by Hernando Yavar. As far as the pediments are concerned, it is known that six pediments were carved in Navarre, of which one is preserved, that of San Fermín. Inspired in its composition by the fabric frontispieces, it combines an exuberant ornamentation centered by the figure of the patron saint. Important pieces are the bust-shaped reliquaries such as the one of Saint Francis Xavier and the one of the Magdalena by José de Yavar of the cathedral of Pamplona. In the line of the enrichment of the images, followed in the 18th century, the image of Nuestra Señora del Camino, patron saint of the city, and the bust of San Fermín in 1682 were covered in silver.

Other religious typologies were the sacras, the lecterns and blandones, although their realizations constitute few examples, among them the lecterns of the parish of San Lorenzo and the sacras of the parish of Corella.

The silversmiths

During the centuries of the Baroque period, Pamplona continued to be the center of Navarrese silversmithing and where most of the silversmiths set up their workshops. The list of active silversmiths in the city is very high, especially in the 18th century when the number of silversmiths examined reached almost one hundred, surpassing the issue mark. The silversmith's official document was passed down from father to son, so that large family workshops were formed, open for several generations, such as those corresponding to the Montalbo, Bentura Jiraud, Yavar, Larumbe, Beramendi, Lenzano and others, which allow us to appreciate the evolution from classicism to Baroque and finally to Neoclassicism. Their members and activity are well known thanks to the study of M. Orbe Sivatte. These family workshops included apprentices and young men and used a large number of complex tools to apply the different techniques used, such as chiseling, engraving, engraving, embossing, casting, as well as mastering the technique of enameling and the handling of precious stones and the alloys and chemical processes necessary in the official document.

Hispano-American silver

The collection of Hispano-American silverware preserved in Navarre makes up a chapter of fundamental importance within Baroque silverware. The presence on our soil of these pieces of rich and exotic appearance from the viceroyalties of New Spain and Peru, as well as Guatemala, is due to the sending of bequests by the Indians for love of their hometowns or for religious reasons. We have quite complete knowledge of these patrons with significant cases such as that of Don Juan de Barreneche y Aguirre who sent in 1748 a spectacular bequest of silverware pieces -two chalices, ciborium, processional cross, naveta, altar, monstrance and reliquary- from Guatemala to the parish of Lesaka. In the same locality we find another outstanding patron, Don Ignacio de Arriola y Mazola, who sent from Lima in 1749 for the construction of the Carmelite convent six boxes of carved silver and also no less than the monstrance of the cathedral of Cuzco that he had bought, adding 10,000 pesos in cash to adorn the piece with diamonds. Another important bequest is the one made by the Marquis of Castelfuerte and Viceroy of Peru Don José de Armendáriz y Perurena who sent from Lima to the chapel of San Fermín de Pamplona five fountains plus two silver jugs and a gold and emerald pectoral for the saint.

bequest from Juan de Barreneche to the parish of Lesaka

PROGRAM

Tuesday, 15th September

The Baroque, an invention of the 20th century?

Javier Portús Pérez. Prado National Museum

Does the Baroque exist in Navarre?

D. Ricardo Fernández Gracia. Chair of Heritage and Art of Navarre

Wednesday, 16th September

"Plegaria de ladrillo y sillar" (Brick and ashlar prayer). Religious architecture in the Navarrese Baroque

Mr. José Javier Azanza López. Chair of Navarrese Heritage and Art

The construction of an image of power: town planning, houses and palaces.

Ms. Pilar Andueza Unanua. Chair of Navarrese Heritage and Art

Thursday, 17th September

Of chisel, hammer and paintbrush. The visual arts at the service of the Church and power

D. Ricardo Fernández Gracia. Chair of Navarrese Art and Heritage.

Jewellery and silver. Adornment and function

Mª Concepción García Gainza. Chair of Heritage and Art in Navarre

presentation of the book Alonso Cano and the Lekaroz Crucifixion

Mª Concepción García Gainza. Chair de Patrimonio y Arte navarro