On the third centenary of the

Chapel of San Fermín (1717-2017)

IDENTITY, ART AND DEVOTION

12 September 2017

The Baroque construction of the chapel

José Luis Molins Mugueta. Chair of Heritage and Art in Navarre

Construction of a new Chapel for San Fermín

There is evidence of the existence of a first chapel dedicated to San Fermín, which, promoted by the City of Pamplona, was consecrated in 1399 inside the parish church of San Lorenzo, a Gothic building at the time, rebuilt in the first decades of the 14th century. In 1534, the Town Council ordered a silver lamp to be carved and made a vow to feed it with oil so that it would shine perpetually before the image of the Patron Saint, in gratitude for having spared the town from a plague, suffered in that same year. Likewise, in October 1599, his devotion intensified, as evidenced by the solemn vow made by the Regiment before the effigy, on behalf of the people of Pamplona, on the occasion of the virulent plague epidemic that struck the city. The desire to erect a more dignified shelter for the image of the Saint, whose pectoral teak was enriched by the incorporation of relics of the titular martyr, donated to the Regiment throughout the 16th century by different bishops of Amiens, led the municipal institution to become the promoter of its current chapel, annexed to the church. The construction process took almost twenty-one years, between the solemn laying of the first stone on 29 August 1696 and the emotional enthronement of the image on 7 July 1717. The work was carried out in accordance with plans drawn up by Santiago Raón, a resident of Calahorra; Fr. Juan de Alegría, a Dominican, resident in Zaragoza; and Martín de Zaldúa, at that time master builder at the basilica of Loyola. The financing, endowed with funds from the Municipality and channelled through the exercise of its board of trustees, finally ratified in 1720, involved Pamplona and Navarre citizens of various kinds, some residing in Madrid, most of them members of the Royal Congregation of San Fermín de los Navarros, which had been set up in the Court in 1684; others, dispersed in the Indies. The City alone made various arrangements until it exceeded a contribution of more than 50,000 pesos. In 1712, 9,000 pesos were sent from the Philippines by the Count of Lizarraga, collected from Navarrese settled there. Years after the inauguration, in 1730, the Viceroy of Peru, D. José Armendáriz, contributed 4,000 pesos of double columnar silver, given to him by Navarrese citizens from his jurisdiction. In Pampona there was no shortage of free work staff services, with the contribution of horses.

General view of the San Fermín Chapel

The authors

In the summer of 1696, the military engineer Hercules Torelli, a Milanese by birth and the son of a general of cavalry in the service of the Most Serene Republic of Venice, who died in Candia during a Turkish siege, was in Pamplona. Torelli, in a memorial addressed to King Charles II that same year, presents himself as a Captain of Horses, Military and Civil Architect, Mathematician and Engineer . It is recorded that he was a Knight of Santiago and that in Pamplona he attended the fortifications of this city . Arriving in Barcelona in 1684, he was protected by the Viceroy and Captain General of Catalonia, Marquis of Leganés, and recommended to the King. Until his death, which occurred in San Sebastián in 1727 or 1728, he devoted himself above all to the survey, repair and updating of different fortifications of the Monarchy, located in Laredo and Santoña (1688), Guipúzcoa (1686,1689), the Andalusian coasts, Oran and Ceuta (1691-1694). He was also involved in civil and religious architecture: Mataró (enlargement of the church of Santa María, 1686); San Sebastián (Monastery of San Bartolomé (1689) and façade of its church (1711), Town Hall and Consulate building (1718-1722), design de la place Nueva -later, de la Constitución- (1723). Unfortunately, most of his work in San Sebastián was destroyed during the siege of the city in 1813. In Pamplona, we owe him the project of the powder magazine of the Citadel (1694), which has been preserved, although with the superfluous loss of the low outer wall, an essential protector in this modality building, in the undesirable event of an explosion. He was also responsible for the catafalque for the funeral of the widowed Queen Mariana of Austria in 1696. In mid-July, the Regiment commissioned Torelli - in the Pamplona documentation, written Turrelli - to survey the parish church of San Lorenzo, and to report on the possibility of building a new chapel dedicated to San Fermín inside it, indicating the best site. He was accompanied in this work by the well-known local master masons Juan de Beasoain and Juan Antonio de San Juan . They decided that the ideal site was the one occupied by the chapel of the Virgen de los Remedios and that it would also be necessary to take a large part of the cloister (which in the end turned out to be all of it). In fact, the construction also affected the chapels of the Espíritu Santo and San Lázaro, in addition to the loss of more than two hundred graves, whose slabs, added to the carved stones of the walls, were sufficient to form the majority of the foundations. In addition, a good portion of the vicarage and the house destined for the main sacristan had to be demolished.

Before the month of July 1696 was over, the Milanese engineer and his two assistants were busy drawing up the plans for the new chapel of San Fermín, when the Regiment learned of the existence of Santiago Raón, a resident of Calahorra, a person of great intelligence and experience in factories, who had indeed built church buildings and other very sumptuous works with great skill. His presence was requested, he went to Pamplona and, in view of the plan presented by Torelli, San Juan and Beasoain, he expressed the opinion that a different one needed to be drawn up, a task for which he offered himself somewhat sibyllinely, on behalf of the aforementioned Juan de Beasuain and Juan Antonio de San Juan. The Corporation accepted his proposal and Hécules Torelli disappeared from the scene.

Santiago Raón was an architect and master builder from Lorraine, born in Mazei around 1635; he settled in Lodosa in 1663, on the occasion of the work on the parish church and its tower. He was the brother of the builder Juan Raón. From 1664 he lived in Calahorra, where he obtained a house and neighbourhood. In 1665 he married Apolonia Merino del Villar, with whom he had seven well-placed children: one of them, José Antonio, was to become an architect. In 1680 he favourably passed the transcript de hidalguía for himself and his successors. He died on 12 February 1701 and was buried in the parish church of Santiago in Calagur. His architectural work reached a high level of sobriety B no Exempt , considering the characteristics of the Baroque period. At an early stage, he appears together with his brother Juan (and in second place, denoting his greater youth). Later the documentation presents him alone.

He designed, directed or participated in, among other works - apart from those already mentioned in Lodosa - in Calahorra: parish churches of San Andrés and Santiago (where he was to be buried); and the façade of the Cathedral (1680-1700). In Viana: Town Hall (1669); San Juan del Ramo (1682); and extension of Santa María (from 1693). In Estella: Church of the Conceptionist Recollects (1688); and Rocamador Basilica (1691). In Corella: dome of Nuestra Señora del Rosario (1696).

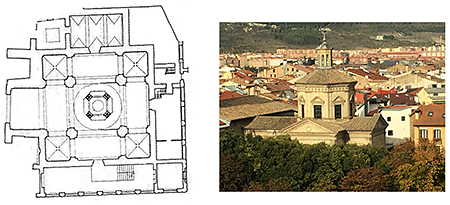

On the left, the ground plan with the primitive altar-throne, shown in a central position, under the dome. On the right, the construction clearly shows its Greek cross plan (photo J. Munárriz).

On 9 August 1696, he presented the plans for the new chapel of San Fermín, in the parish church of San Lorenzo, referring to the ground plan and elevation. And five days later, he provided those corresponding to the orange average and the hornato that the chapel was to have . The City was pleasantly recognised for the speed of execution and beauty of the design, and agreed to pay fifty pesos. With all solemnity and in the presence of the Diocesan Bishop, the Viceroy and the Municipal Corporation, on the 29th of August, the old ceremony corresponding to the laying of the first stone was performed. Up to this point, Santiago Raón appears as the sole author of project. But in later documentation, specifically in a lawsuit brought by the Regiment against some masons, it is said that the drawing up of the ground plan and elevation was due to Juan de Alegría, a religious of the Order of Preachers, resident in the city of Zaragoza, Santiago Raon, a resident of Calaorra and Martin de Zaldu, resident in Loyola, in the province of Guipuzcoa, and that, signed by the said masters and the secretary ynfrascrito, can be found at administrative assistant of the Consistory. This participation of Alegría and Zaldúa is also mentioned in the municipal conference proceedings . I consider it a very plausible hypothesis that both signed the basic aspects of the ground plan and elevation previously drawn up by Santiago Raón. Although they would undoubtedly have made corrections.

Martín de Zaldúa Aguirre, who belonged to a family with several stonemasons, was born in Asteasu in 1654 and died in Azpeitia in 1726. He was an influential builder, currently considered to be the introducer of Madrid-influenced Baroque architecture in Guipúzcoa and Vizcaya. He also cultivated wooden altarpieces. When the Regiment requested his transfer to Pamplona in September 1696, he was master builder of the Sanctuary of Loyola (1693-1709), for which he had designed the "imperial staircase" in 1692. He was responsible for architectural works in Bilbao, Vergara, Azpeitia, Hernani, Oñate, Eibar, Lequeitio and Ispaster, among others. And wooden altarpieces in Abando, Arrigorriaga and Bérriz; plus a choir stalls in Azpeitia.

Baroque Paradigm

The exterior

The chapel of San Fermín was built in the period of the Ornamental Baroque, which we can frame for Navarre between 1660 and 1730. This is the Hispanic phase of the apotheosis of the style, with its traditional and delirious ornamentation, which combines a scarce movement of floors and elevations with the profuse and exuberant plastic decoration of the architectural elements themselves and of the facings. Despite the neoclassical reform carried out between 1800 and 1805, according to project by Santos A. Ochandátegui, today the exterior of the building is fully Baroque. The preference for the central plan takes the form of a Greek cross inscribed in a square, with four quadrangular spaces at the ends, plus a nexus section, which joins it to the church of San Lorenzo. On the outside, the complex is embraced by a double wing with the pretensions of a palace, on two floors, the lower one in stone with large arcades, and the upper one in brick and with straight openings, one and the other with grilles. The front wall - like the adjoining wall - has an oculus between four projections with the heraldic arms of Pamplona, in ceramic. These brick walls are crowned with triangular pediments. The octagonal drum and the lantern, the latter rebuilt in 1824, rise above it.

Ochandátegui's reform mainly affected the internal space, although it also affected the exterior. In fact, we are going to deal with a specific plastic aspect located here. The aforementioned quadrangular enveloping body hints at four sides, although it only has two - unequal in length - as the other two are occupied, on one side by the church of San Lorenzo, and on the other by the farmhouse. The bay aligned with the doorway of the parish church has eight arches, while the other has six, of which the last one is partially embedded in the residential building, which corresponds to issue 18 of the Rincón de la Aduana. A painting by Miguel Sanz Benito, kept in the Municipal Museum of Pamplona, file , which depicts the episode around the time of O'Donnell's uprising in October 1841, graphically testifies to this aspect as already existing at that time in the 19th century.

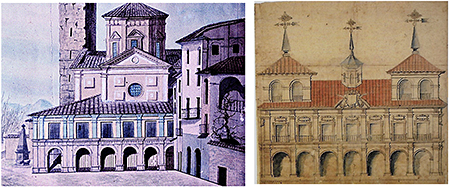

On the left, aspect of the enveloping body of the Chapel in the mid-19th century ( M. Sanz Benito, Sublevación de O'Donnell en 1841-detalle-. file Municipal de Pamplona ). On the right, Santiago Raón, design of the façade for the Town Hall of Viana.

But beyond that there is another arch, which appeared relatively close to the present date, in the spring of 2008, when the wall that concealed it was demolished in the course of interior re-painting work at portal. It does not differ from the previous ones, nor does the upper part of the entablature that is visible. It is no different from the preceding ones, nor is the upper part of the entablature visible. The opening is sample blinded by a brick wall, and it bears the mark of an old solid circular oculus and perhaps also the imprint of an earlier rectangular opening (oculi were common in the building at the time of its neoclassical renovation). The councillors of 1696 conceived the perimeter circuit of the chapel as a stage for processions, when bad weather prevented them in the streets. However, the finding would not be of great importance if it were not for the plastic motif that the core topic of the arch exhibits as an ornament: none other than the representation of a green man topic of great diffusion in the time and geography of different cultures. It is the representation of a human face through the employment of vegetal elements, in the form of scrolls, which, in this case, frame the eyes, in the form of a tuft on the forehead and aladares on the position of the temples; as well as those located instead of cheeks and lips, around the mouth, in which teeth and language are signified in a natural way. As so often happens in sculpture, the protruding nose has disappeared, the victim of time or an occasional unfortunate blow. The sculpted subject is an easily carved limestone, whitish in tone, well differentiated in chromatic tone from the neighbouring greyish voussoirs. This mask retains perceptible traces of black paint on the eyeball, which, like the iris and pupils, would accentuate the expression of the eyes.

On the left, blind arch located inside portal of dwellings, with traces of a rectangular window later transformed into an oculus.

On the right, detail of the green man in the core topic of the previous arch (Photos. I. Castiella).

It seems that each and every one of the exterior arches of the chapel had its corresponding green mansculpted in the respective core topic. In fact, today the same whitish stone can be seen on employment for all the keystones or central voussoirs. Undoubtedly for Ochandátegui's architectural statement of core values it was essential to purify the arcades of anecdotal elements of baroque lineage, dispensing with masks that were felt to be caricatures. To this end, the keystones were chiselled, which made it possible to match their surface with the smooth course of the threads without any major complication.

Moreover, in the initial project of Raón and consorts, the openings of the stone arches may have been solid brick, with rectangular slit windows, which were converted into oculi during the reforms undertaken between 1800 and 1805. In 1806 the Cathedral Chapter sold the iron grilles -331 arrobas and 25 pounds in weight- from the chapels of the then reformed cathedral, to make, after casting, the grilles that now close the gallery leave of the exterior circuit of the Chapel of San Fermín. The arches were then left diaphanous and open to the air, as is clearly attested by the aforementioned picture, painted by Sanz Benito in 1841, in all its arches, except for the one that has remained hidden until now, which remains as a witness to the preceding status .

The interior

The interior baroque decoration disappeared during the refurbishment undertaken at the end of the 18th century, which will be described at accredited specialization. Exuberant and profuse, it was the object of the academic dicterios, fulminated by Antonio Ponz, following his trip to Pamplona in 1793. It can ideally be reconstructed from the descriptions published at the time, from documentary research and through preserved images, captured in engravings or on canvas. And it is also possible to apply analogous criteria: in 1708 the Tudela sculptor José de San Juan y Martín presented a project and designs for the ornamentation, masonry and whitewashing of the chapel, its frontispiece and sacristy, which once C, was finished off by Fermín de Larráinzar. The walls and pilasters with their plinths, bases and capitals were carved with exquisite architecture . The frieze of the entablature and the threads of the arches were decorated with carvings, flowers, boys and fruit . Similar decorative treatment was displayed on the great dome, which centred the internal space and from which hung a carved wooden fleuron, almost five metres in diameter (seven feet). Thirteen tribunes - two of which served as choir stalls - had their balconies, enclosed with gilded latticework on a green field, over the interior: each one was topped by a card and three pendant fleurons. In general terms, the ornamental plastic criterion of the chapel of San Fermín was similar to that applied in the case of the chapel of Santa Ana in Tudela cathedral, which is practically the same time. Furthermore, it is more than likely that José de San Juan was involved in the decoration of the chapel in Tudela.

The ornamentation of the Chapel of Santa Ana, in the Cathedral of Tudela, is similar to that of the Chapel of San Fermín, before its refurbishment.

The documentary sources of the time speak of a double frontispiece as the entrance to the enclosure inaugurated in 1717: the exterior one, of considerable size, similar to the present one, seventeen metres high and approximately half as wide, and comparable in proportions to the trono-altar executed by Onofre, which was located at Wayside Cross, exactly under the dome. Its exterior arch was crowned by a figure of the titular Saint in a cloud, which is the same as the representation of the apotheosis of San Fermín. The inner façade was somewhat smaller. Both were profusely decorated with carvings and full-length sculptures, including images of the Evangelists on pedestals, and in different sections representations of the Virtues, both Theological and Cardinal, with a multitude of angels. The façade was extensively reformed during the work of Santos Ángel de Ochandátegui, stripped of sculptural elements to leave it, respecting its dimensions, in the line it has today, severe and linteled, on corbels. In the attic, framed by a mock curtain, two angels now hold a medallion with the scene of the martyrdom of San Fermín.

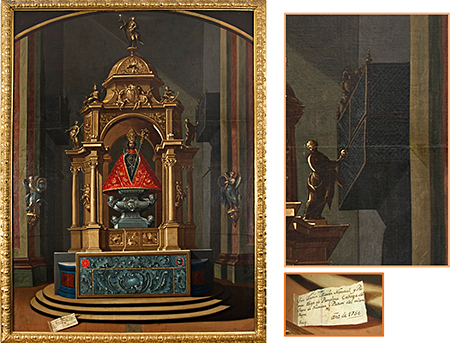

The throne o baldachinmade of Aragon pine wood, initially built to house the image of the titular saint, was dismantled and removed from its location, centred under the dome, in 1793, when the dome of the Chapel showed signs of leaks and serious damage due to damp. From that moment on, its trace was lost. However, it is possible to reconstruct an approximate ideal image by means of contemporary documentation and some preserved figurative testimony: this is the case of the canvas reproduced here, painted by the painter Rada in 1756. The author of this throne-tabernacle was Pedro Onofre Descoll, a sculptor active in Aragon and Navarre at the end of the 17th century and during the first third of the 18th century, with a workshop in Saragossa, whose work is documented, although much of it has disappeared. As for the throne, we should point out that it stood on a circular tier of three steps, made of stone from Ablitas. Its square floor plan, which had four openings about seven metres high, topped with an arch, facing the four naves of the Greek cross that articulated the Chapel, evolved into an octagonal nave as it ascended, and finally culminated in a dome topped by a small lantern. Profusely decorated with mouldings and plant motifs of flowers and fruit, it included an extensive iconographic programme, with representations in bulk. Its interior was gilded by José García, the same master who had gilded the Baroque tribunes of the enclosure, which have now disappeared. The piece showed the influence of the tabernacles with baldachin, typical of the Madrid school, in turn inspired by the funerary architecture of ephemeral catafalques. The large proportions of the artefact, almost seven metres wide (26 feet) and, above all, the seventeen metres high (65 feet), allowed it to compete with the magnitude of the frontispiece of entrance to the Chapel. The scenographic character of the throne was enhanced by a coloured tile pavement, which spread out in front of its four sides, like carpets, under the light of the dome.

Oil painting by Pedro A. Rada, painted in 1756, depicting the altar-throne of San Fermín (file Municipal de Pamplona). The detail reproduces one of the balconied tribunes of the Chapel, with latticework.

As a Baroque example of the integration of the arts, it is worth noting that in 1736 the decoration of the chapel was completed with the addition to its walls of five large paintings, with scenes from the life and martyrdom of Saint Fermín, the work of the painter Pedro Antonio de Rada, then a resident of Vitoria.

The chapel was built opposite the façade of the Gothic parish church, which at that time opened onto the Calle Mayor on the Gospel side. The last section of the parish church served as a passageway from that doorway to the Sanferminero enclosure itself, a passageway which was spatially accentuated on the left-hand side by the presence of a gate, known as a januado. In this way, a rectilinear space of visual tension was created, in the manner of a via sacra, which focused on the frontispiece of the chapel. (The present church dedicated to San Lorenzo is the result of a neoclassical plan by Juan Antonio Pagola, drawn up between 1805 and 1810, which in its day included a doorway in an identical position to the original one, directly opposite the Chapel of San Fermín, traces of which can still be seen today in the ashlars of the exterior wall, facing the place de las Recoletas).

An unusual inaugural procession

This year marks the three hundredth anniversary of the inauguration of the Chapel of San Fermín. An obligatory occasion to evoke the religious and building celebrations held in July 1717, for which purpose it is useful and even essential to visit enquiry of an anonymous book, printed in the Pamplona workshop of Juan Joseph Ezquerro, with the here simplified degree scroll Relacion de las Plausibles Fiestas con que ha celebrado la Ciudad de Pamplona, Cabeza del... Reyno de Navarra, la Translacion de su Gran Patron San Fermin de la Antigua Capilla a la Nueva... The reading, which is not necessarily easy, gives a full descriptive idea of the architecture, decoration, iconography and other data of artistic interest, referring to the enclosure; data which are interwoven with religious or social references, defining an era. Suffice it now to mention the attendance of the Regiment at the function on the afternoon of the sixth of July, with the customary entourage, music and solemn protocol . The accompaniment was very varied, both from Pamplona and from abroad; but, above all, the abundance of the crowd was surprising; and, in the manner in which the wily journalistic chronicles quantify the attendance to demonstrations of any kind, it could be said that as soon as the Corporation had left the Town Hall, the first companions were already arriving at the Taconera. They went to San Lorenzo, on whose altar was the image of San Fermín, and the Capilla de Música of the Cathedral fulfilled its role with the singing of Vespers.

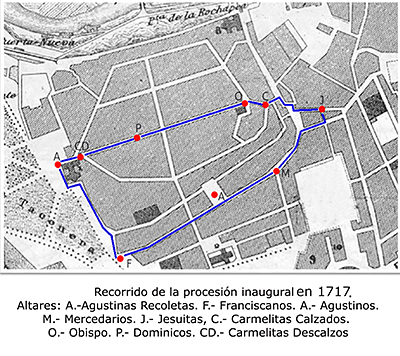

At ten o'clock the following morning, seven o'clock, the Regiment set off for the Cathedral, accompanied by guilds with banners, parish councils, religious communities and the people. Six formidable giants and two tarascas led the procession. Once the procession was formed in the cathedral, they went to San Lorenzo, where the effigy of the Saint was taken. The procession went out to place de Recoletas through the door, which in its position corresponds to the current condemned one. It is B the fixity of the custom: the processional route has not changed in three centuries. At nine points along the well-known route, nine other altars were erected, generally at position of different religious communities, an example of what we know today as ephemeral architecture, not for its temporary limitations devoid of creativity, beauty or ingenuity; in any case, they are an example of a internship very typical of the Baroque period and appropriate to its mentality. In all of them the Saint stopped and before continuing a carol was sung. And so, under the medieval tower of San Lorenzo, where the door of the parish church is today, the Augustinian Recollect Nuns had erected their altar, with urns of relics of various saints. As an aside, it is worth noting that when the procession arrived at the height and in front of the citadel, the artillery and the fusiliers fired a Royal Salute . At the end of Calle San Antón, at the height of the now disappeared convent of the Antonianos, the altar prepared by the Franciscans, which combined ingenious geroglyphics and poetry, was waiting. In the small square of committee awaited an image of St. Augustine on a pyramid, an ensemble designed by the Augustinians. The Mercedarians prepared their altar in Calle Salineria (Zapatería), near the Pozo de la Sal: it combined in the form of a triple pine cone the statues of San Pedro Nolasco, San Ramón Nonato; and above it was an image of the Virgen de las Mercedes. In Calle del Mentidero (now Mercaderes), opposite issue nueve(Casa del Mayorazgo de Don Josseph de Caparroso), the Jesuits had erected the most B of the buildings erected by the Communities: Four triumphal arches on as many columns supported a small garden with flowers and live birds; and in this area were San Ignacio de Loyola, San Francisco Javier - Co-patron saint of Navarre - and San Francisco de Borja, above which towered the image of San Fermín, dressed in pontifical vestments. The columns and arches on which the altar was raised were large enough to allow the procession to pass under them, as indeed it did. The Calzados Carmelites erected their tabernacle at the confluence of Nueva and Bolserías (San Saturnino) streets: it featured Mount Carmel, with caves, hermits in prayer, domestic and wild animals; from the upper part-where the Virgin of Mount Carmel stood-waterfalls of water flowed down, powered by small mills.Next to the doorway of the church of San Saturnino and next to the well of tradition, the bishop of Pamplona, Don Juan de Camargo, had arranged for the placement of a scene depicting San Fermín kneeling, receiving the baptismal waters that continuously fell from a shell held by the right hand of San Saturnino. In a higher plane, the Phoenix Bird was being reborn from the flames. Halfway along the Calle Mayor, the Dominicans erected their altar in front of the house of the Marquises of San Miguel de Aguayo, at the time high school of the Teresian Sisters: the images of Saint Dominic of Guzman, Saint Thomas Aquinas, Saint Vincent Ferrer, Saint Rose of Lima and other saints of this Order could be seen. Finally, near the confluence of Calle Mayor and Calle San Lorenzo, there was the last monument, due to the initiative of the Discalced Carmelites, consisting of a marquee arch and a small garden in which, apart from the statue of Saint Teresa of Jesus, other saints belonging to the Reformed Carmelite Order were placed.

Finally the procession entered the church of San Lorenzo, from where San Fermín was taken to his new chapel and placed on his throne. The Te Deum was then intoned and a solemn mass was immediately celebrated, which was celebrated by Don Pedro Martínez de Artieda, Prior and Canon of the Holy Cathedral Church, in the absence or impossibility of the Bishop. Once the service was over, the attendees went to the first diocesan temple, from where the Regiment returned to the Town Hall.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

-ANDUEZA UNANUA, P., La arquitectura señorial de Pamplona en el siglo XVIII. Families, town planning and city. Pamplona, Government of Navarra-Principe de Viana Institution, 2004.

-ANONIMO, Relacion de las Plausibles Fiestas con que ha celebrado la Mui Noble y Mui Leal Ciudad de Pamplona, Cabeza del Ilmo. y Fidelissimo Reyno de Navarra, la Translacion de su Gran Patron San Fermin de la Antigua Capilla a la Nueva, que ha fabricado con su devocion. Sacala to the public, and offers it to the same city one of his most devoted sons. Pamplona, Imp. de Juan Joseph Ezquerro, year 1717.

-FERNÁNDEZ GRACIA, Ricardo (Coord.) El arte del Barroco en Navarra. Pamplona, Government of Navarra, 2014.

-GARCÍA GAÍNZA, M.C. ET AL, Catalog Monumental de Navarra.V***, Merindad de Pamplona. Pamplona. Pamplona, Institución "Príncipe de Viana", Archbishopric of Pamplona, University of Navarra, 1997.

-MOLINS MUGUETA, J. L., Chapel of San Fermín in the Church of San Lorenzo de Pamplona.. Pamplona, Diputación Foral de Navarra-Institución "Príncipe de Viana", Pamplona City Council, 1974.

-MOLINS MUGUETA, J. L.An example of "green man" in the Chapel of San Fermín in Pamplona.

PROGRAM

Tuesday, 12th September

The baroque construction of the chapel

José Luis Molins Mugueta. Chair of Heritage and Art in Navarre

The multiplied image of Pamplona and other representations of San Fermín in Navarre

Ricardo Fernández Gracia. Chair of Heritage and Art in Navarre

Wednesday, 13 September

The academic reform of the chapel

José Luis Molins Mugueta. Chair of Navarrese Art and Heritage.

protocol and ceremonial around San Fermín

Alejandro Aranda Ruiz. Chair of Navarrese Heritage and Art

Thursday, 14th September

The treasure of San Fermín: pieces of liturgy and devotion

Ignacio Miguéliz Valcarlos. Chair of Navarrese Heritage and Art

The cult of San Fermín in the graphic collections of file Municipal of Pamplona

Ana Hueso Pérez. file Municipal of Pamplona