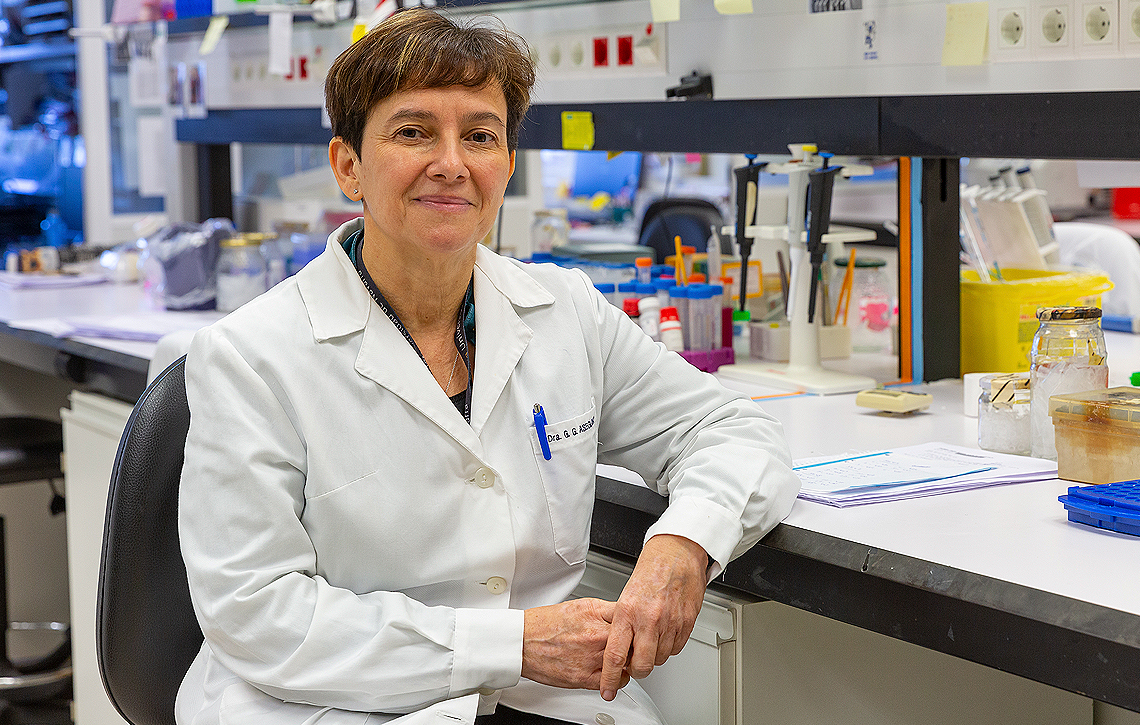

In the picture

Gloria González Aseguinolaza is the scientific coordinator of the Rare Diseases research line of Strategy 2025.

Today, Gloria is an expert in gene therapy. "It's about using genetic material as a drug to cure diseases," she explains. And she soon realises that it sounds a bit far-fetched. He adds: "When you want to treat a disease you have to go to its cause in order to provide a solution. What do you do to treat an infectious disease? You remove the pathogenic agent: the virus or bacteria that causes it. And what do you do to treat a tumour? You eliminate it. In the case of genetic diseases, their cause is in the genes, so you have to act on them in order to cure them.

Gloria is deputy director of Cima and, for the past year, has been coordinating the research line on Rare Diseases in the University's Strategy 2025. These pathologies, as defined in Europe, are those that affect 1 person in 2,000, and most of them usually have a genetic origin. But although each individual disease is suffered by a very small number of sufferers, collectively more than 300 million people in the world suffer from a rare disease. "And possibly these numbers are not real because there are many people who will never be diagnosed because they do not have access to, for example, a genetic diagnosis," says Gloria.