26/08/2024

Published in

Diario de Navarra

Carlos Mata

group de Investigación Siglo de Oro (GRISO)

These days the supposed "philological enigma" of the "lance in the shipyard" of Alonso Quijano / Don Quixote de la Mancha ("... not so long ago there lived a nobleman of those of the lance in the shipyard, old adarga...", Don Quixote, I, 1) is once again in the news.", Don Quixote, I, 1), which would have been resolved by the archivist and researcher José Cabello Núñez, with an explanation adopted by Andrés Trapiello in his most recent version into current Spanish of Don Quixote, as ʻlanza a punto de ser usadoʼ and, therefore, "lanza en ristre". In the grade spread by the EFE agency last August 8, signed by Alfredo Valenzuela ("Archivero resuelve el enigma filológico de ʻlanza en astilleroʼ del principio del Quijote"), and later reproduced in several media, we read: "The misunderstanding with the meaning of ʻen astilleroʼ took a long time to be resolved because it is an expression that the Diccionario de Autoridades does not record. And, as Trapiello himself explains with some irony in the prologue to the latest edition of his translation, published this year, he himself relied on the notes of philologists who claimed that ʻastilleroʼ was an armory for storing shafts and weapons. ʻSome of these philologists even illustrated it with a very nice drawing. It is a pintiparada reconstruction of what in their opinion was a 'shipyard' in which there would be no lack of adargas, lanzones and other junkʼ. Trapiello adds it with the irony that characterizes so many of his writings".

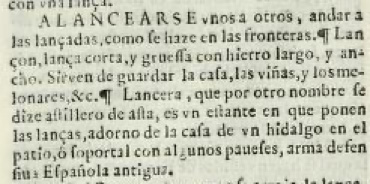

Now, to be precise, it should be pointed out that "astillero", with this literal meaning, does appear in the dictionaries of the period, specifically in the Tesoro de la language castellana o española (1611) by Sebastián de Covarrubias. It is true that it does not appear as such voice, "astillero", but it is recorded among the various derivatives of "lanza", in the subvoice "alancearse": "Lancera, which by another name is called astillero, de asta, is a rack where they put the lances, ornament of the house of a nobleman in the courtyard or porch, with some paveses, an old Spanish defensive weapon".

Definition of "lancera" or "astillero" in the Tesoro de la language castellana o española (1611) by Sebastián de Covarrubias, s. v. alancearse.

Testimony, moreover, nothing new, as it had already been adduced by many of the annotators of Don Quixote. Ignacio Arellano, in a entrance of his blog El jardín de los clásicos of July 23, 2015, "La lanza en astillero -que no olvidada-de don Quijote", exposed with very sensible reasons, after recalling Correas' definition (these words were a response to Trapiello's original interpretation ʻlanza olvidadaʼ): "So someone knows what a shipyard is. And this being an ornament -that is, an exhibited symbol of social quality- of the house of a nobleman, it is not plausible that the lance was in oblivion: it was, yes, an ancient lance, a weapon of Don Quixote's ancestors, long inactive, but the placement in the shipyard reveals precisely that its owner wants to make clear his nobility and his military vocation. He was, let us not forget, fond of hunting, a substitute exercise for war. A forgotten lance is placed in an attic, in the stable, in a stairwell, with other useless objects. But this is not what happens with Don Quixote's lance. Every day, when leaving or entering his house, the ingenious hidalgo would see his lance in the shipyard, his ancient adarga -not forgotten-, giving him silent voices, and something inside him would accumulate enough energy so that he would finally pack his shield, wield that lance that every day attracted his gaze, and go out to run his adventures through the ancient countryside of Montiel and throughout the whole world. No, Don Quixote's lance was not in oblivion. It was exactly in the shipyard".

Shipyard with lances in the Torreón del Gran Prior (Alcázar de San Juan, Ciudad Real). Photo: Carlos Mata Induráin (2019).

In a similar sense, Enrique Suárez Figaredo expressed himself in a article published in Lanza Digital. Diario de la Mancha on May 1, 2019, "La interpretación pertinente de ʻlanza en astilleroʼ":"Why read figuratively what has a straight reading? The yard (not ʻastillaʼ, but ʻastaʼ) for a spear is something similar to what is used for hunting rifles. [...] Was it to be kept in the back of a closet buried by coats? That a son-of-something villager should have an old spear in his yard, not ʻbehind the doorʼ, evidences the melancholy and proud recollection of the deeds of his ancestors."

It is clear, then, from the definition provided by the Tesoro de Covarrubias (remember its date: 1611), that the shipyards ʻestantes to place the lancesʼ existed in reality; and let us not forget the fact that they were "adornment of the house of a nobleman", as was Alonso Quijano, a nobleman -that is- who dreamed of being a knight-errant.

It is also worth remembering -although it is obvious- that a word or an expression can have different meanings, depending on the context and the status in which it is used. The fact that a word means something does not mean that it means it always and everywhere. I will give a simple example: the word "bank", among several other meanings, can mean ʻfinancial institutionʼ or ʻplace to sitʼ. The context and the status lead us to understand different things if someone says: "I go to the bank, because I need to withdraw money" or "I go to the bank, because I need to rest". Well, something similar happens with the expression "estar o poner algo en astillero". It is true that in the letter of a royal commissioner of supplies, from 1595, located by Cabello Núñez where he speaks of flour and wheat "puestos en astillero", the expression is effectively valid ʻestar listos, preparados para ser recogidosʼ; and the same in the passages adduced by Trapiello as for example "ya tenéis vuestro libro en astillero", from El pasajero ( 1616), by Cristóbal Suárez de Figueroa. But the expression, in other contexts, can mean something else. A simple enquiry to the Corpus diacrónico del español(CORDE, online) is enough to locate numerous examples of the expression "en astillero", among them the definition given by Gonzalo de Correas in his Vocabulario de refranes y frases proverbiales ( 1627): "Estar en astillero. Lo ke no está en perfezión, komo las naves akabadas de fabrikar de madera sin averlas akabado de adornar" (I keep the spellings that Correas wanted for his text). It seems to me that this definition has not been pointed out, at least in the statements and interviews of the last few days.

On the other hand, several of those examples that CORDE brings, corresponding to passages from picaresque novels, testify to the meaning ʻwith the appearance ofʼ that the expression "ponerse en astillero" has. For example, in Aventuras del high school program Trapaza, quintessential embusteros y maestro de embelecadores (1637, degree scroll significant), we read: "One of the things that hindered Trapaza was to have put himself in the shipyard of such a great gentleman in Madrid, fleeing not a little from being seen where the Portuguese were; because, as the Court is large, it was easy for him to excuse the occasions of meeting them, to avoid them wanting to be informed of his person, of whom he had to give a bad report if they asked him things about Africa." The necessary context to understand this passage is that the rogue Hernando protagonist of the novel, the high school program Trapaza, pretends to be a Portuguese nobleman of possible, Don Vasco Mascareñas, to contract a marriage (that he believes very advantageous) with the widow Estefanía: the rogue has put himself "in shipyard" of gentleman, that is to say, he has adopted the false appearance of gentleman and does not want to meet people (the Portuguese) who could unmask him. And in La niña de los embustes, Teresa de Manzanares, by the same author, we have the same expression, "poner en astillero", with the same meaning of ʻadopting a false or deceitful appearanceʼ: "Marcela was telling me that I was to blame for what I was with, because I had given wings to the ant to fly; this was to have put in the shipyard of a lady who was a slave".

I do not mean, far from it, that the latter is the operative meaning of the famous phrase at the beginning of Don Quixote, I only intend to show that the expression "estar o poner en astillero" can mean different things depending on the context and the status in which it is used. And, yes, Don Quixote's lance could very well be materially and literally in the shipyard of his nobleman's house, being an ornament of it (as Correas' definition qualified), not yet "en ristre", but already exercising that silent call to chivalrous adventures that Arellano commented on, a sensible and simple explanation for which -permit me the play on words- I now break a lance.