"It is time to rethink the concept of responsibility to accelerate the transition of our Economics towards greater environmental sustainability."

The researcher Loris de Nardi has studied thanks to a scholarship Marie Curie how fire risk reduction in the Modern Age financial aid us to face climate change.

PhotoNataliaRouzaut/

31 | 07 | 2023

Loris de Nardi holds a PhD in History and Comparison of European Political and Legal Institutions from the University of Messina (Italy). The researcher has developed the project LOWRISK 'The role of the reform of civil liability in the reduction of fire risks in the Iberian Peninsula (XVIII and XIX centuries)' at the Institute for Culture and Society of the University of Navarra thanks to a Marie Curie scholarship , one of the most prestigious offered by the European Commission. According to the expert, who specializes in public policies for disaster risk management , we have entered a new geological stage known as the Anthropocene. This stage is characterized by the impact of human activity on terrestrial alterations. Climate change, with its resulting extreme events and sea level rise, "was due to human activity and this is not reflected in historical theorizing," he warns. To understand how we can take responsibility for the indirect consequences of our actions on the planet, de Nardi has investigated a similar phenomenon: civil liability for fire risk in modern Iberian societies.

Can you summarize what the project is about?

My project wanted to reflect on how modern and colonial Iberian societies managed fire and how they tried to reduce the risk of fire. They are pre-industrial societies and they need fire to develop many daily activities. My project wanted to see how, from the 16th to the 19th century, these societies managed to protect themselves and reduce the risk of fire, because both Iberian and Americanist historiography paid very little attention to fire.

How did these companies protect themselves from the risk of fire?

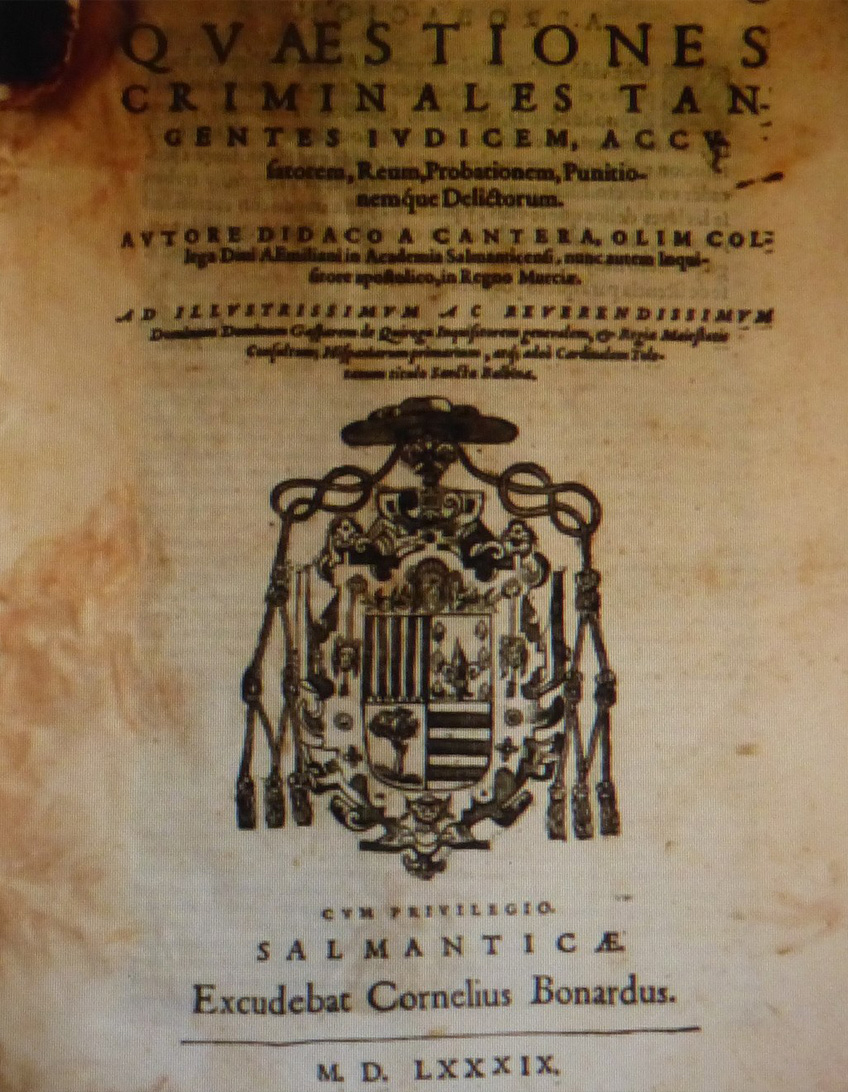

Institutions see the need to regulate fire management, to make the population use fire in a manager and diligent manner. However, this was problematic from a legal point of view since modern Hispanic law, especially Criminal Law, is still medieval law. Modern medieval law is none other than Canon Law. The Church was the first to sanction the law with the goal to reconcile the sinner with the divinity.

"Happiness, which is a subjective right, has been elevated to Constitutional Law"

What does it mean that the legislation was based on the Canon Law?

We have two consequences. On the one hand, there is a proportionality of punishment: not all acts are equally serious before the divinity. Thus, it is not possible to punish in the criminal regional law (which would be today's criminal) involuntary acts and most fires, of course, are involuntary. Only compensation for damages was obliged. Nothing could be said, even if you walked with a torch into a haystack or piled up a pile of gunpowder in the center of town.

On the other hand, the legal culture of the time prevented the punishment of negligent or reckless behavior that had not been intentional in the criminal regional law with corporal sanctions. Thus, during the modern era, institutions try to find alternative ways to extend this limit, which is a cultural limit.

How was this legal culture overcome?

During the 18th century, an important cultural change took place which, among other things, led to the bourgeois revolutions at the end of the 18th century and which, with the codification of the 19th century, made it possible to include what we know as culpable crimes, which did not exist before.

The main change (and this was the starting hypothesis of my research) is that the idea of some rights that are natural, that is to say, that they are subjective rights, proper to the human being, begins to be defined. And, among these rights, there is security but, above all, there is the right to property. In other words, the need to protect property began to be recognized.

Why does this happen?

Because enlightenment identifies property as a way to achieve happiness. So, if I allow fire to get out of control, it destroys property and does not allow the State to guarantee happiness to the population, which is its main goal. Happiness, which is a subjective right, has been elevated to Constitutional Law and, therefore, the State has to protect it. With the passage to liberal ideals, the bourgeois see that happiness is identified with property. And this is because, for example, the right to property guarantees access to a whole series of other rights, such as the right to vote. Fire destroys houses, businesses, work and thus leads to the impoverishment of the population. For this reason, in the 19th century we find, for example, the creation of insurance companies or fire companies.

Finally, during the 19th century we have codification, that is, the rules that had been promulgated during modern and medieval times, custom, etc., are systematized and reformulated in a clearer and more modern language. This work, which may seem technical, is actually political. The nineteenth-century codifier can decide which norms to maintain, which norms to remove, which norms to modify, or which new norms to invent to solve new problems that the populations of previous eras did not have. Even more important, the codes serve the bourgeois class , which thanks to the Atlantic revolutions has become the leading class , to implement the principles and ideals sanctioned by the written constitutions. Thus, we can say that the codes, far from being neutral tools of government, allowed the bourgeoisie to consolidate its political hegemony.

In the words of Pio Caroni, we can affirm that "it was true that the code addressed everyone in the same way, granted everyone the same freedom, obliged everyone to the same discipline and imposed on everyone the same rules of the game. But that did not make it everyone's code. It was still the code dreamed of and desired by some, it was therefore a code for a part of it."

What did the codification of law entail?

The nineteenth century Codes, i.e. the Civil Code, the Commercial Code, the Criminal Code, take the opportunity to innovate. And among the main innovations in the criminal field we find negligent offenses. The reduction of fire risk is one of the first areas in which the culpable offenses intervene. Penalties begin to appear for the involuntary crime of fire for those fires that were not caused by malice but by recklessness or negligence.

Clearly, they were able to do so because it was a need that society had long been aware of. Some judges, as early as the eighteenth century, had begun to punish with corporal punishment those responsible for unintentional fires. But these were isolated sentences. But with the promulgation of the penal codes, everything changed. Culpable crimes are typified. The legislator identifies certain evils that affect society and this, by itself, justifies punishment by the State. Then, it is necessary to discipline the population so that it understands that it has to behave diligently. Through a system of sanctions for certain acts, the population must know that these acts are wrong.

But these are after-the-fact sanctions, aren't they?

These are administrative sanctions, i.e., you cannot enter a haystack with a torch. With the Penal Code they solve that problem. There was a sanction that prevented you from doing this, you did it, you caused a fire and now I punish you. It is interesting that, soon after, codifiers went one step further: negligent offenses opened the way to recklessness. From the forties and fifties of the nineteenth century, in the codes we no longer find, for example, the crime of arson, but a much broader and more effective typology, recklessness, which allows the legislator to punish without the need to identify all those acts that could be defined as reckless and potentially dangerous to the rights or interests of others. When reviewing the judicial records, we realize that many of these reckless acts have to do with the handling of fire.

"The state's priority is no longer to punish but to prevent behavior."

What are the implications of these sanctions?

Awareness was based on a radical change in the conception of punishment, another 18th century innovation that was implemented in the 19th century. Before, criminal punishment served to reconcile the sinner with divinity. Now there are two new theories. One is the theory of utility. Penalties have to be useful so that the population understands that they cannot carry out certain acts.

The other is the psychological theory, i.e., the State is authorized to exert psychological coercion on the population to prevent it from committing certain acts. Therefore, the State's priority is no longer to punish but to prevent behavior by including deterrents in the legal system to convince people to behave prudently. Acts can be punished because, in the end, they show that the individual no longer fits into the idea of society, which must have as goal respect for the rights of others.

It is interesting that, during the 19th century, a new punishment modality appears: jail. The jail was previously the dungeon where you were put while awaiting trial. Now prisons are in themselves a place of punishment, the penitentiary, where you enter to receive a discipline that allows you to be reintegrated into society.

Can it be said that the law follows a cultural change?

Law is a historical product and as such is a cultural product. Law evolves throughout history. We see it today, for example, with sanctions for acts that were not crimes before. Each society has its parameters and, therefore, resorts to law to discipline and punish. With respect to arson, in the past, the crime of negligence was something that could not be conceived of. This changes after the Atlantic revolutions with an acceleration towards a more secular society where crimes are no longer sins.

Why did you focus specifically on the risk of fire in the Iberian Peninsula in the 18th-19th century?

Because there are historiographical reasons. First, very few historians have devoted themselves to that topic and, in general, to disasters. On the other hand, because I am convinced that, what the society of the 18th-19th centuries did with respect to fire, is a challenge very similar to the one we have today with climate change.

It is essential to reconsider our notion of responsibility in the context of climate change.

Climate change is a historical and political product. We are producing it and, therefore, it is we (i.e. our species) who have to stop it. The problem is that national legal systems, under the logic of a national society based on solidarity, are based on mutual responsibility: the individual is accountable for the impact of his or her actions on other members of the community. On the other hand, the subject initially manager is exonerated from his obligations if the non-performance was due to a fortuitous event: an event attributed to an external cause, considered impossible to foresee with the means at his disposal; irresistible, even if all possible precautions had been taken; and independent of his will, fault or negligence. However, it must be asked whether this ancient legal doctrine is still entirely viable in our present day.

In fact, as observed already some years ago by Myanna F. Dellinger, "its foundation lies in the idea that humans are somehow separate from nature and that only nature can be blamed for extreme weather events that are unpredictable, unpredictable and unavoidable. However, technology and the modern knowledge have proven this to be false." So it is urgent to rethink it, redefine it and clarify it, taking into consideration that we became a geological force and that many of the extreme natural events are caused by our actions. I am increasingly convinced that it is time to rethink the concept of responsibility to accelerate the transition of our Economics towards greater environmental sustainability in the fight against climate change. Similar to how modern societies had to address fire management when realizing the urgent need to reduce fire risk, addressing climate change requires widespread awareness along with direct state intervention to set limits on all actors responsible for CO2 emissions. By studying how we succeed in reducing fire risk, we can learn valuable lessons that help us understand the importance of addressing climate change in a holistic manner.

It is essential to reconsider our notion of blame or responsibility in the context of climate change. Currently, we tend to attribute blame only when there is a direct and obvious relationship between a specific action and its negative consequences. For example, we cannot directly blame large oil companies for the increase in hurricanes, as there is no immediate and visible connection between their operations and extreme weather events.

"We have to think about liability reform."

However, we know that the increase of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere contributes to global warming, which, in turn, is related to the increased frequency and intensity of hurricanes. This is where the idea of an indirect liability relationship comes into play. If an individual or corporate action contributes to increased CO2 emissions, even if it does not directly result in a specific hurricane, it does contribute to the broader phenomenon of climate change and its destructive consequences. Current thinking focuses on the possibility of considering these indirect relationships when assessing the responsibility and consequences of our actions. If someone or an entity contributes to climate change indirectly, i.e., if their actions contribute to the increase in CO2 and thus to climate change, they could be held responsible and subject to appropriate measures or sanctions to reduce those negative contributions. This broader and more comprehensive approach of responsibility is essential to effectively address climate change, as it is not only a matter of directly blaming those who cause an extreme weather event, but also of recognizing and correcting the actions that, as a whole, are leading to environmental degradation and its consequences.

Can History of Law help us today to legislate for people to be more prudent?

Seeing how we tried to reduce risk and trying to analyze the cultural changes that allowed us to do so and the solutions to the extent rules and regulations may be one more occasion to reflect on how to deal more carefully with change today.

And do you think these cultural changes are occurring today to support legal change?

If not today, it will be tomorrow. All scientific communications tell us that we are already reaching a point of no return and it cannot be just for an autonomous movement of the citizen. Certain measures have to be taken at a higher level and cannot do without a coercive element. We have to think of new regulatory measures that will allow us to hold accountable those who are the main producers of climate change. In other words, we need to think about accountability reform. The same as our ancestors had to do during modern and contemporary times to reduce the risk of fire. Although the global climate status is in the public domain, current legal systems continue to consider the biosphere "outside the community". Thus, many events that should be attributed to humans continue to be imputed to nature and operate as an exoneration of responsibility. For this reason, different operators of the law and exponents of the academic community denounce the need to evaluate the possibility of contracting parties being called upon to face greater risk at the individual level in the future, given that, although it is still impossible to trace or search for the origin of climate change in general, there is no doubt that, in some way, we are all guilty of it.

However, even if the population is aware, large companies can use their power and economic influence to prevent these laws from being implemented if they do not benefit from them.

Sure, but this on a smaller scale always happened. We live in a time where the Economics seems to be more important than politics, but we have many examples in the past where big decisions were made by politics and the Economics had to respect them. For example, I think of France, Germany, Italy after World War II. In the end, it was political decisions that made it possible to create the welfare society.

Today, the stakes are much higher. Two months ago, a survey by American journalists revealed that a major oil company had knowledge, since the 1960s, that fossil fuel consumption would lead to a rise in global temperature. This raises an urgent question: What are we going to do about it? If one business knew, it is very likely that all of them were aware of this reality. It is true that oil companies are not solely responsible for the unnatural disaster we call climate change. However, if we really want to reverse this status, it is imperative that legislators become aware of their role and promote changes in legislation that will allow them to sanction both these companies for their lack of action and any behavior that generates risks for the environment.

The status is pressing and we must act with determination. Climate change is not a problem we can ignore or leave for future generations. It is crucial to take decisive action to hold those who had knowledge accountable for the devastating impact of their actions and prevent future damage. However, this task goes beyond simply creating stricter laws or implementing strong measures to protect our planet and ensure a sustainable future for all. It is also necessary to rethink our understanding of responsibility, delving deeper into its scope and consequences. Only in this way will we be able to comprehensively address the challenge of climate change and ensure a true transformation to a more sustainable world.

Are there any conclusions you would like to highlight from the research?

There are two. First, once again, it has been possible to demonstrate that law is a cultural product and, therefore, in order to understand law we cannot do without a historical analysis that explains why we have certain rules today.

Secondly, the fire shows us that natural disasters do not exist and that, from the human and social sciences, we can make a significant contribution to raising public awareness of some concepts that we take for granted. For example, natural disasters do not exist, they are historical processes result of the vulnerability of certain populations to hazards. They become a risk because the natural manifestation, fire in this case, finds a vulnerable status .

There is always risk, but it must be kept under control, managed and the population and, therefore, the ruling classes must be made aware of it. This is essential so that change can take hold in society and make a difference.

"We are the ones responsible for the planet entering a new geological stage."

Could you highlight any activity you have done?

In the framework of my Marie Curie, I made two instances of improvement and research. The first one at department of Private, Social and Economic Law at the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, under the supervision of Javier Barrientos Grandon. There I had the opportunity to confront myself with several pure jurist colleagues and to understand, above all, the difference between civil and criminal law and how crimes are included in the nineteenth century criminal codification.

The other was a stay at the Max Planck Institute for Legal History and Legal Theory in Frankfurt. This stay allowed me to have access to the main Iberian journals of the 19th century and to carry out a systematic research of all the archives. By reading these archives I was able to reconstruct the discussion around guilt as an element of culpability.

In addition to this, during the Marie Curie I was able to consolidate an academic experience that I had already started before: the network Geride, which started in 2019 and, between 2021 and 2023, we managed to organize more than 20 sessions on disasters. Last year, in December, one of the sessions was specifically dedicated to responsibility, which was the main theme of Marie Curie. These seminars are now internationally recognized. Now in July, for example, we have another session where more than 20 researchers will participate.

Any academic publication to highlight?

I have 3 articles in indexed journals that were published as result of the Marie Curie. First I published a article that deals with programs of study related to disasters and its management throughout history with a colleague from Universidad de los Andes.

Another is focused on the discipline of arson throughout the colonial era and the nineteenth century and delves into how nineteenth-century society tried to stigmatize the figure of the arsonist in an attempt to dissuade the population. They also did so by resorting to the novels of submission, a genre of popular literature of the 19th century. Analyzing these novels, the arsonist is always the criminal par excellence and always ends badly.

Another article talks about the Anthropocene, which was the idea that pushed me to propose this project. The proposal was to reformulate the periodization of Western history and create this new periodization that makes explicit the fact that we are entering the Anthropocene. That is, the idea that we are responsible for the planet entering a new geological stage.

And what are the next steps for your research?

Now I want to focus on how guilt in the criminal sphere could be justified in the first decades of the nineteenth century and what were the motivations that led the nineteenth-century legislator to include negligent offenses in the codification. It is a matter of reading many treatises, many articles of the time, because, although the criminal codes included the crime of negligence and were approved by the various courts and enacted, this left open several wounds in the legal world. There were many debates to understand what this fault was because they did not know it and not everyone was in agreement agreement. In the end, it was a doctrine that had existed for several centuries and had people who supported it. We are facing a legal world where not everyone thinks of it in the same way, nor do they understand the need to punish guilt. They only think of punishing the voluntary act. This could be one of the next investigations.